经济去金融化:要做什么?

De-financialising the economy: what is to be done?

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/de-financialising-economy-what-be-done/

By Ben Wray 10 October 2019

De-financialising the economy: what is to be done?

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/de-financialising-economy-what-be-done/

Tackling the power of finance head on is essential if we are to address the urgent challenges of our time. But it won't be easy.

This essay is part of ourEconomy's 'Preparing for the next crisis' series.

The Labour Party’s 2019 annual conference was a cornucopia of radical policy announcements, as the party prepares to fight an imminent general election. But one area where the conference was noticeably quiet was the centre of Britain’s financialisation regime: the banking sector.

Proposals for re-purposing majority-state owned RBS remain on the table, but there is little by way of concrete reform plans – regulatory or otherwise – for challenging the power of private finance as a whole. The recent establishment of a “City Surgery” indicates a growing desire to reassure banks about the party’s plans in office.

Indeed, some head honchos in the City of London appear to be coming round to the idea that a Labour government may be preferable to the alternative.

“Is Corbyn as bad as no-deal? Perhaps no longer,” Christian Schulz, at Citi bank, told The Telegraph.

Of course, financialisation is not simply about the banks, and thus an agenda to tackle it has to be much more systematic than reform of the financial sector. Policies such as scrapping tuition fees and tackling student debt would undoubtedly contribute to de-financialising the UK economy.

However, the beating heart of financialisation is the financial sector (including ‘shadow banking’), and its brain is the system of regulatory and legal rules upheld by the state which re-produce the conditions for finance to dominate the economy.

Unless the heart and brain of financialisation is tackled, attempts to cut off its limbs will likely prove ineffective.

This essay will explore strategies for de-financialisation, based on the following assumptions:

a) Financialisation, understood as the dominance of “financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions”, is currently hegemonic in the global economy;

b) Financialisation is incompatible with an approach to economic development which takes social and environmental justice seriously; and

c) The next crisis will invariably be a crisis of financialisation.

With this framework established, we can proceed to address the question of strategy – the ‘what is to be done?’ question.

War of position, or war of manoeuvre?

Two main strands of thought within de-financialisation literature can be identified, which I will call incrementalist and rupturalist strategies.

The incrementalist strategy seeks to eat away at financialisation through reforms which build new institutions at the macro and micro level which can over-time develop into an alternative to the commercial banks, while introducing regulatory changes which limit, without breaking, finance’s reach into key aspects of the economy, such as housing and education.

Incrementalist policy approaches include an ambitious public infrastructure investment plan based on state-owned investment banks, supporting the establishment of worker co-operatives and policies on land and housing which seek to restrict financial expropriation and rental extraction, including giving the Bank of England a remit to restrict house price inflation.

James Meadway, economist and former advisor to shadow Chancellor John McDonnell, has advocated an incrementalist strategy, arguing that “to transform finance, we need a slow, methodical process akin to defusing a bomb — not a further explosion.”

He goes on: "It will mean ‘structural reforms’ to our economy — building new institutions to deliver investment, like the regional development banks; changing the ownership and control of productive assets, for example through the Inclusive Ownership Funds”.

In a paper specifically on de-financialisation for the IPPR think-tank in 2014, Mathew Lawrence also advocated structural reforms based on a similar reticence about the speed of change which was possible, arguing “boldness of intent must…be matched with a recognition that change will be painstakingly achieved…Reversing financialisation will not be an easy or swift endeavour”.

Lawrence’s proposals do pertain to the financial sector specifically, arguing for a new Bank of England mandate on monitoring and guiding credit creation, new regulatory institutions including a Financial Product Board to assess new financial products and a British Future Fund which would skim off the proceeds of the financial sector to build up to what eventually would be a £100 billion sovereign wealth fund for long-term, sustainable public investments.

The rupturalist strategy argues that incremental reforms will never make headway against a system that has been designed around the interests of the financial sector. Even if incremental changes did make progress, unless finance’s base of power is taken away from it, reforms are likely to be over-turned again further down the line. The rupturalists instead advocate a full-frontal offensive on the financial sector. Policy approaches include nationalisation of the banking sector, debt write-downs/write off’s and capital/credit controls.

Costas Lapavitsas, SOAS economist and author of ‘Profiting Without Producing’, is an advocate of a rupturalist strategy, arguing that “there are no clear paths of regulatory change to confront financialisation”.

According to Lapavitsas, “If it is necessary to adopt a more interventionist attitude toward finance than merely setting a regulatory framework, then property rights over financial institutions ought to be considered directly... Controlling finance as a system would acquire a different complexion, if public ownership and control over banks were re-introduced systematically.”

He goes on: “In principle, there would be no intrinsic difficulty in publicly managing the flow of credit to households and non-financial enterprises to achieve socially set objectives as well as to eliminate financial expropriation.”

In a different way, Kingston University economist Steve Keen argues in ‘Can we avoid another financial crisis?’ that “indirect government action” to address financialisation is likely to fail to bring down private debt to GDP levels, citing the example of Japan where there has been an increase in public spending to GDP for almost every year since it’s more than quarter of a century long stagnation began in the early 1990’s, but private debt levels remain stuck at around 165 per cent of GDP (similar to the UK’s).

“If neither market nor indirect government action is likely to reduce private debt sufficiently, the only options are either a direct reduction of private debt, or an increase in the money supply that indirectly reduces the debt burden,” Keen writes.

Keen makes the case for private debt levels to be reduced to significantly below 100 per cent of GDP to ensure financial stability, and argues for debt-write off’s and/or a form of helicopter money which he calls a ‘modern debt jubilee’. This is where authorities would make “a direct injection of money into all private bank accounts, but require that its first use is to pay down debt”.

While incrementalist and rupturalist approaches have genuine and important differences, in political strategy terms they do not be fundamentally at odds with one another. If we understand politics as the ‘art of the possible’, where timing is king, both incremental and ruptural approaches have their place. The key is to understand the Minskyite cycle of finance-led growth and crisis, and how a political strategy must adapt itself to the specific phases of that crisis.

At times of finance-led growth, incremental reforms can help to re-balance power as far as possible between “those who live off wealth and those who live off work”, as economist Grace Blakeley puts it, with the understanding that the political conditions for a knock-out blow of financialisation do not yet exist.

As well as some of the incremental reforms proposed above, government should support the emergence of organic forms of resistance to finance capital, including debtors unions, tenants unions and stronger workplace organisation. It should also utilise fiscal and monetary policy in such a way that wage inflation is always higher than that of assets, eroding the value of debts over time.

Another key role in this period is to build an electoral coalition for de-financialisation, by providing quite diverse demographics with clear incentives and a stake in a de-financialised Britain, in a similar way to how Thatcher’s housing reforms built a new demographic for Tory politics.

A ‘reverse Thatcherism’ can act to prepare the ground for the key battles to come when the financial system inevitably implodes. The proposal for a right-to-buy policy for private tenants, floated by John McDonnell, is one example of reverse Thatcherism, which could be co-ordinated through regional investment banks to cut out the banking sector, with additional incentives for those who are willing to club together with other formerly private tenants in their block to form co-operative housing entities.

At times of financial crisis, the political conditions alter utterly. An incrementalist approach is not only limited – it is also useful for the defenders of financialisation, who become quite happy to concede some ground in the short-term, as long as the state acts to protect their vital interests. State action becomes inevitable during a crisis: the only question is what form it takes; whether the state acts to prop up that system or de-construct it. In this moment, a rupturalist strategy becomes essential in both resolving the crisis, and as a bridge to establishing a new economic order.

We can understand this dual strategic approach by (mis)using the Gramscian strategic dichotomy of war of position and war of manoeuvre. The war of position is understood as the struggle for influence; whereas the war of manoeuvre is the struggle for control.

The war of position therefore pertains to the phase of debt-fuelled growth, and the war of manoeuvre to the moment when that growth cycle inevitably crashes. It is the crisis phase that will be the focus of the rest of this essay.

Crisis response strategies: unpicking a bomb, or performing surgery on a malignant disease?

It is vital to understand the psychology which informed the “first responders” of the 2008 crash, which is how the key figures of the United States’ response thought of themselves according to Adam Tooze in his monumental history of the Great Recession, ‘Crashed’:

“The metaphors…position the crisis-fighting team as first responders facing a compelling emergency. And they place us, their audience, by their side. Who would not root for the fatherly Ben Bernanke trying to keep the family car on the bridge, or [Timothy] Geithner’s heroic bomb disposal team? Politics is set aside as we anxiously watch our heroes struggle to rescue us from disaster. There is no time to ask why this happening. We are 'all in this together'. But it is precisely with that assertion that a political economy of the crisis begins. Which system was it that needed to be saved in the autumn of 2008. Who was being hurt? Who was included in the circle of those who needed to be protected? And who was not?”

This crisis response took “off the table” the structural problems of financialisation which brought the crisis to being, in order to “give absolute priority to saving the financial system” which “shaped everything else that followed”, according to Tooze.

It was the psychology of first responders that informed an OECD paper on crisis response strategies published as the 2008 financial crash was ripping through the world economy. Blundell-Wignall, Atkinson and Se-Hoon concluded that: “The basic lesson of the past solvency crises is that three steps are always required:

1. Insure all relevant deposits during the crisis to prevent runs on banks.

2. Remove the ‘bad assets’ from the balance sheet of banks.

3. Recapitalise the asset-cleansed banks.”

The state is always crucial in clearing out ‘bad assets’, rather than market mechanisms, the authors found. Why?

“The reason is because only the public sector can issue risk-free assets and exchange them for risky assets in a crisis, which is critical when liquidity is jammed and there is widespread uncertainty and a buyers strike on the part of natural holders such as pension funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds and the like.”

The OECD accepts that private sector actors are incapable of resolving a crisis of their own making, and that the systemic risk of the financial sector’s bad assets is too great to allow them to go to the wall. But what then happens after the state intervenes on a loss-making basis to cleanse banks of their bad assets?

“Much later, in the exit strategy phase, the public sector assets can be sold: gradually removing them from the public balance sheet towards more natural holders such as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance companies and other investors. Depending on the pricing of assets, and how the process is handled, the taxpayer could eventually recoup some of the losses from the costs of the rescue packages.”

This is bailout economics – the epitome of socialism for the rich, capitalism for the poor. The public sector takes on bad assets from banks and then sells them to private investors at a loss to the public purse when they become attractive assets again. The government is then left with a higher level of debt, the banks are left with a healthier balance sheet, and private investors are left with assets acquired on the cheap. Meanwhile, those on the other side of the ‘bad assets’ equation – households and businesses – receive no bailout, and lose their home or have to wind up their enterprise.

In different ways and at different speeds, this was broadly the approach that nation-states pursued in 2008. In some countries the state nationalised or part-nationalised bank assets, in others assets were auctioned off to investors – but almost always with the aim of exiting the crisis in such a way as to defend and uphold financialisation.

A de-financialisation crisis response must have the urgency of Geithner and Bernanke’s metaphors, but rather than being considered as an emergency from an exogenous threat, like an explosive device, it must be depicted as an endogenous development which has reached the point of an emergency, like a malignant disease which has caused a cardiac arrest and now requires surgery, or an addict who has over-dosed and needs a major intervention.

In this way, the crisis response is connected to the long-term strategy: surgery paves the way for the doctor to conduct chemotherapy and other treatments to fix the patient; saving the addict requires emergency treatment followed by a long-term recuperation plan which fundamentally changes the person’s way of life.

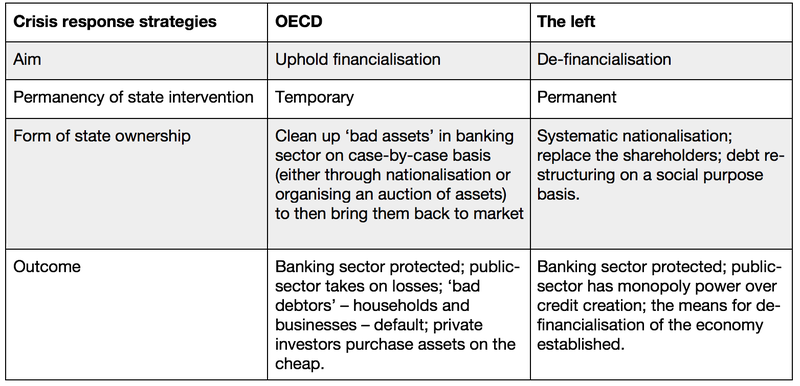

What does this mean broadly in policy terms? The following table conceptually separates out crisis response strategies between that proposed by the OECD and that of a de-financialisation agenda pursued by the left.

Just as the OECD outline three phases, or steps, to their crisis response strategy, the left’s strategy must also be phased in a way which:

a) Resolves the crisis in the short to medium term; and

b) Makes a decisive shift towards the long-term de-financialisation plan.

There is insufficient space to thoroughly debate the detailed policy implications of such an approach (which in any case requires further research and policy development), but the steps which are required for a de-financialisation crisis response strategy may look like the following:

Step 1: Nationalise systematically, not on a case-by-case basis. Starting with the institutions where the risk to the UK economy as a whole is systemic, the aim should be to eventually bring all credit creation into public control. This is the key link between crisis response and de-financialisation – by taking credit creation into public ownership, the rate and direction of investment in the economy can be controlled.

Step 2: Ensure confidence in the financial sector. Guarantee all deposits. Inject liquidity where necessary.

Step 3: Introduce capital controls. Preventing capital flows out of the country will be essential in keeping financial markets in check.

Step 4: Implement a systematic evaluation of the credit portfolio, including a plan for a major debt write-down’s and write-off’s to reduce the private debt to GDP burden. Guarantee no repossession of homes or business properties from defaults. Explore the potential for a sale of some foreign assets to reduce international exposure.

Step 5: Re-design finance with new social purpose criteria. Re-write regulations to eliminate financial expropriation from hedge funds and private equity firms; transform pension fund investment criteria and create transparent accounting practices; write a new tax code to prevent avoidance; reform ‘shareholder value’ in company law; etc.

Step 6: Resolve the crisis in the interests of the majority. A huge fiscal stimulus to ensure full employment; plans for improving provision of universal services that were previously heavily financialised (e.g. education, public transport, housing) to reduce the cost of living.

The barriers to de-financialisation

The de-financialisation crisis response strategy outlined above would face formidable barriers.

In an economic sense, the most important challenge would be the pressure placed on the UK’s exchange rate by international financial markets. This will be particularly challenging in relation to the domestic banking sector’s foreign debt liabilities; specifically, access to dollar liquidity. The role of the Federal Reserve as “global lender of last resort” during the 2008 crash was barely known about at the time, but has since been revealed to have been absolutely instrumental, “transforming what we imagine to be the relationship between financial systems and national currencies”, according to Tooze.

Britain has a financial sector which is uniquely internationalised, as Tony Norfield shows in ‘The City’. UK financial services exports are worth 2 to 3% of GDP, a figure five or six times higher than for the US, and it has by far the largest total loans to, and deposits from, other countries of any major economy, totalling a massive 16.7% of UK banking. And that’s not including the string of UK controlled tax havens around the globe. One of the key challenges this presents is therefore how to deal with foreign-owned banks operating in the UK with substantial UK-based assets.

Politically, the strategy outlined above would be an existential threat to UK financial elites, who would muster all of their enormous lobbying power to stop it. If the financial sector itself is held off, there is then a broader coalition of benefactors from financialisation – private equity firms, pension fund managers, landowners, landlords, property owners – who could be forged into a bloc with the aim of disarming any de-financialisation agenda.

Institutionally, there will be a massive challenge in getting the state to respond to crisis in the way we’ve described above, both in terms of the close relationships between the permanent representatives of the state in the civil service and financial elites, and in terms of the lack of experience of state actors in leading the sort of actions that would be necessary to make de-financialisation happen.

But far from being concerned with a revolving door between the financial sector and government, the Treasury argued in a review of its crisis response published in 2012 that a “higher degree of staff exchange with other institutions” would have been helpful, despite noting the organisation’s high turnover was partly due to “officials returning to other organisations after short spells on loan or secondment at the Treasury”. This is a glimpse into the depths of the institutional challenge the left would face.

If the institutional culture of the Treasury would be problematic, the institutional independence of the central bank would potentially be deadly. The strategy outlined here would require the Bank of England to be working in lock-step with the Treasury, willing to take unprecedented power over the banking sector, and wield that power in a way that is anathema to its present remit. The Bank of England gets its mandate from the Treasury, but control over the bank on a day-to-day level is independent from government influence. The Bank of England’s raison d’être is to protect the financial sector first and foremost. It’s not clear that a change in its remit would be sufficient to deliver a de-financialisation crisis response strategy – the vexed question of central bank independence may have to be confronted head on.

There would also potentially be an institutional challenge at the intra-national level, depending on Britain’s relationship with the EU at that time, with rules preventing controls on capital at EU level potentially acting as an impediment.

Legally, the ownership proposals here could come under challenge if the sector is nationalised in its entirety, rather than on a failed bank-by-bank basis, due to stringent UK property laws, and potentially a challenge at the European Convention of Human Rights. There is also the potential for debt restructuring to be challenged on a legal property basis.

In non-crisis times, this combination of barriers would likely make a full-frontal attack on the proprietors of the financial sector too dangerous to pursue for a left government. But the weakness of finance is its high-risk dimension, which means that it needs the state to break with governing norms to protect it in times of crisis.

Instability is built into the logic of finance-led growth. In a political environment of a mass movement against the banks where it loses hegemony in society as a whole, the government can be put in a position where the barriers to a de-financialisation crisis response strategy suddenly do not look as daunting as upholding the status quo.

A case study in de-financialisation: Iceland

It’s not within the scope of this essay to attempt to answer conclusively all of the barriers identified above – further research and policy development is required on that front. Beyond posing questions and suggesting possible answers, we can look to one of the few examples from the 2008 crash which at least partially disproves the pessimistic view that there is no alternative to bailout economics.

Iceland responded to the 2008 crash with “a series of conventional and unconventional policy actions” which led to “a certain degree of de-financialisation”, According to Björn Rúnar Guðmundsson, in his study of financialisation and financial crisis in Iceland.

An Emergency Act broke up the three big banks into a new bank for domestic activities and an “old’ bank for international activities. The government also pledged to guarantee all bank deposits. Then, capital controls were introduced that meant “all capital account transactions were prohibited in order to prevent the exit of financial assets, most of which were held by foreign investors”. Capital controls ended up lasting until 2017, “impeding general financial sector recovery”.

These two policies were the foundations for a transformation in banking portfolios and activity. All loans transferred to the new banks were-revalued “on a fair value basis”. The focus of the banks became about “debt restructuring and balance sheet repair” while “market turnover in the foreign exchange market, the equity market, and the bond market plummeted”.

The outcome was a profound de-leveraging across the economy, especially in the business sector. Corporate debt fell from over 300 per cent of GDP just before the crash to under 80 per cent by 2014 as a result of systematic “write-downs and write-off’s”. Household debt fell more slowly, but by 2014 it had reduced to 2005 levels.

The clean-up of bank balance sheets has proved enormously successful, even for the banks, which have “revalued their portfolios upwards and report profits accordingly”. In this way, Guðmundsson finds, “the originally impaired loan portfolios have over performed relative to expectations in the wake of the crisis.”

The outcome is Iceland’s economic development model has fundamentally changed, with “a shift away from financial-led towards increasingly export-led growth”. The drop in the value of the Krona internationally during the crisis provided the basis for an export-led recovery, with the country recording a current account surplus in 2014 for the first time in over a decade. The current account deficit peaked in 2006 at 23 per cent of GDP.

The combination of international political pressure to comply with European Economic Area (EEA) rules and a re-assertion of the domestic political power of finance led to the end of capital controls in 2017. With foreign debts and international capital flows only slowly beginning to re-assert themselves, it’s too soon to say if the neoliberal model is back, but this does highlight the limitations of Iceland’s partial de-financialisation.

While Icelandic banking was re-organised, it was not sufficiently re-purposed, with short-term profitability remaining the key driver. Despite this, Iceland is evidence that while the barriers to de-financialisation are formidable, they are not insurmountable, especially if the depths of the crisis of financialisation is profound.

Conclusion

An interesting thought experiment, which we will never know the answer to, is the following: if Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell were in charge during the 2008 crash, rather than Gordon Brown and Alistair Darling, would things have turned out any differently?

McDonnell has certainly been thinking about this. Richard Barbrook, founder of the group ‘class wargames’ which was behind the viral General Election game ‘Corbyn Run’, has been advising the shadow Chancellor’s team on war gaming a crisis in a Labour government.

“A run on the Pound, an exodus of investors and a financial crash like the one that struck the global economy in 2008 are the types of scenarios the team will try to respond to,” PoliticsHome reported.

It’s clear that McDonnell especially is a deep thinker about how socialists should utilise government power in a neoliberal economy, knowing that he will not necessarily have many organic allies. Across large sections of British industry there is no workers movement to speak of, and across the Western world there are few socialists in power to act as international allies. He can’t even rely on his own backbench MPs.

What appears to be McDonnell’s thinking is that, given those circumstances, survival will be the first order of the day. Not to be forced out of office by the power of finance will be an achievement in and of itself. With that in mind, the shadow chancellor may be satisfied with the financial sector’s growing ease towards the idea of a Corbyn-led Labour Government.

But, as the futurist writer Alvin Toffler put it, “if you don’t have a strategy, you’re part of someone else’s strategy”. While it may be comforting for Labour to feel like The City has been neutralised as a political threat to the party’s electoral prospects, finance will also be looking to subdue any radical reforms from Corbyn and McDonnell which could threaten its power.

In the age of financialisation, if a left government does not go on the offensive against the power of finance, can it really expect not to pay the price at some future point down the line? Plus, in a crisis-ridden financial system, can the major contradictions of financialisation really be left unresolved by a Labour Government, à la 2008? And can a Labour government realistically face up to the urgent challenges of our time – including but not limited to climate breakdown, inequality and poverty, a demographic crisis and automation – while allowing finance to remain in the saddle of the British economy?

None of these questions have easy answers, but avoiding them will only see problems accumulate. The ‘what is to be done?’ question about finance needs urgent attention.

Ukraine's fight for economic justice

Russian aggression is driving Ukrainians into poverty. But the war could also be an opportunity to reset the Ukrainian economy – if only people and politicians could agree how. The danger is that wartime ‘reforms’ could ease a permanent shift to a smaller state – with less regulation and protection for citizens.

Our speakers will help you unpack these issues and explain why support for Ukrainian society is more important than ever.

Read more

- Here’s how Humza Yousaf can deliver a fairer, greener ScotlandWritten by: Adam RamsayAll Articles By:Adam Ramsay

- Breaking corporate monopolies is the only way to save democracyWritten by: Nick DeardenAll Articles By:Nick Dearden

- UK government lets airlines off the hook for £300m air pollution billWritten by: Lucas AminAll Articles By:Lucas AminWritten by: Ben WebsterAll Articles By:Ben Webster

- Don’t be fooled by childcare pledges, Hunt’s budget offers the bare minimumWritten by: James MeadwayAll Articles By:James Meadway

Image: Matt Crossick/PA Archive/PA Images

Image: Matt Crossick/PA Archive/PA Images