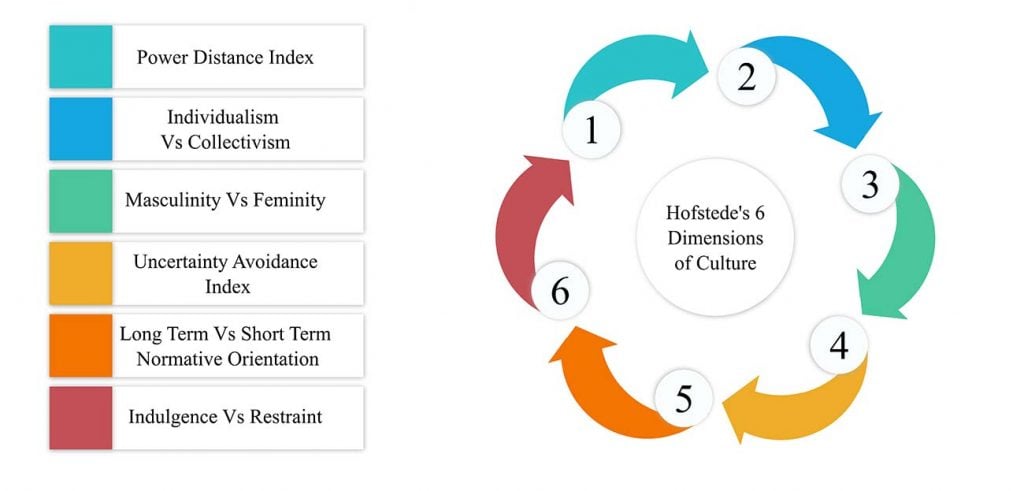

Cultural dimensions theory was proposed by the Dutch psychologist Geert Hofstede to explain the differences between national cultures. He believes that culture is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from others. Through factor analysis, he summarized the differences between cultures into six fundamental dimensions of cultural values, as shown in the figure below:

https://www.simplypsychology.org/hofstedes-cultural-dimensions-theory.html

a replication of Hofstede’s study, conducted across 93 separate countries, confirmed the existence of the five dimensions and identified a sixth known as indulgence and restraint (Hofstede & Minkov, 2010).

Cultural Dimensions

[hofstede cultural dimensions]

Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory (1980) examined people’s values in the workplace and created differentiation along three dimensions: small/large power distance, strong/weak uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and individualism/collectivism.

Power-Distance Index

The power distance index describes the extent to which the less powerful members of an organization or institution — such as a family — accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.

Although there is a certain degree of inequality in all societies, Hofstede notes that there is relatively more equality in some societies than in others.

Individuals in societies that have a high degree of power distance accept hierarchies where everyone has a place in a ranking without the need for justification.

Meanwhile, societies with low power distance seek to have an equal distribution of power. The implication of this is that cultures endorse and expect relations that are more consultative, democratic, or egalitarian.

In countries with low power distance index values, there tends to be more equality between parents and children, with parents more likely to accept it if children argue or “talk back” to authority.

In low power distance index workplaces, employers and managers are more likely to ask employees for input; in fact, those at the lower ends of the hierarchy expect to be asked for their input (Hofstede, 1980).

Meanwhile, in countries with high power distance, parents may expect children to obey without questioning their authority. Those of higher status may also regularly experience obvious displays of subordination and respect from subordinates.

Superiors and subordinates are unlikely to see each other as equals in the workplace, and employees assume that higher-ups will make decisions without asking them for input.

These major differences in how institutions operate make status more important in high power distance countries than low power distance ones (Hofstede, 1980).

Collectivism vs. Individualism

Individualism and collectivism, respectively, refer to the integration of individuals into groups.

Individualistic societies stress achievement and individual rights, focusing on the needs of oneself and one’s immediate family.

A person’s self-image in this category is defined as “I.”

In contrast, collectivist societies place greater importance on the goals and well-being of the group, with a person’s self-image in this category being more similar to a “We.”

Those from collectivist cultures tend to emphasize relationships and loyalty more than those from individualistic cultures.

They tend to belong to fewer groups but are defined more by their membership in them. Lastly, communication tends to be more direct in individualistic societies but more indirect in collectivistic ones (Hofstede, 1980).

Uncertainty Avoidance Index

The uncertainty avoidance dimension of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions addresses a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity.

This dimension reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with their anxiety by minimizing uncertainty. In its most simplified form, uncertainty avoidance refers to how threatening change is to a culture (Hofstede, 1980).

A high uncertainty avoidance index indicates a low tolerance for uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk-taking. Both the institutions and individuals within these societies seek to minimize the unknown through strict rules, regulations, and so forth.

People within these cultures also tend to be more emotional.

In contrast, those in low uncertainty avoidance cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or changeable environments and try to have as few rules as possible. This means that people within these cultures tend to be more tolerant of change.

The unknown is more openly accepted, and less strict rules and regulations may ensue.

For example, a student may be more accepting of a teacher saying they do not know the answer to a question in a low uncertainty avoidance culture than in a high uncertainty avoidance one (Hofstede, 1980).

Femininity vs. Masculinity

Femininity vs. masculinity, also known as gender role differentiation, is yet another one of Hofstede’s six dimensions of national culture. This dimension looks at how much a society values traditional masculine and feminine roles.

A masculine society values assertiveness, courage, strength, and competition; a feminine society values cooperation, nurturing, and quality of life (Hofstede, 1980).

A high femininity score indicates that traditionally feminine gender roles are more important in that society; a low femininity score indicates that those roles are less important.

For example, a country with a high femininity score is likely to have better maternity leave policies and more affordable child care.

Meanwhile, a country with a low femininity score is likely to have more women in leadership positions and higher rates of female entrepreneurship (Hofstede, 1980).

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Orientation

The long-term and short-term orientation dimension refers to the degree to which cultures encourage delaying gratification or the material, social, and emotional needs of their members (Hofstede, 1980).

Societies with long-term orientations tend to focus on the future in a way that delays short-term success in favor of success in the long term.

These societies emphasize traits such as persistence, perseverance, thrift, saving, long-term growth, and the capacity for adaptation.

Short-term orientation in a society, in contrast, indicates a focus on the near future, involves delivering short-term success or gratification, and places a stronger emphasis on the present than the future.

The end result of this is an emphasis on quick results and respect for tradition. The values of a short-term society are related to the past and the present and can result in unrestrained spending, often in response to social or ecological pressure (Hofstede, 1980).

Restraint vs. Indulgence

Finally, the restraint and indulgence dimension considers the extent and tendency of a society to fulfill its desires.

That is to say, this dimension is a measure of societal impulse and desire control. High levels of indulgence indicate that society allows relatively free gratification and high levels of bon de vivre.

Meanwhile, restraint indicates that society tends to suppress the gratification of needs and regulate them through social norms.

For example, in a highly indulgent society, people may tend to spend more money on luxuries and enjoy more freedom when it comes to leisure time activities. In a restrained society, people are more likely to save money and focus on practical needs (Hofstede, 2011).

Correlations With Other Country’s Differences

Hofstede’s dimensions have been found to correlate with a variety of other country difference variables, including:

geographical proximity,

shared language,

related historical background,

similar religious beliefs and practices,

common philosophical influences,

and identical political systems (Hofstede, 2011).

For example, countries that share a border tend to have more similarities in culture than those that are further apart.

This is because people who live close to each other are more likely to interact with each other on a regular basis, which leads to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures.

Similarly, countries that share a common language tend to have more similarities in culture than those that do not.

Those who speak the same language can communicate more easily with each other, which leads to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures (Hofstede, 2011).

Finally, countries that have similar historical backgrounds tend to have more similarities in culture than those that do not.

People who share a common history are more likely to have similar values and beliefs, which leads, it has generally been theorized, to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures.

Applications

Cultural difference awareness

Geert Hofstede shed light on how cultural differences are still significant today in a world that is becoming more and more diverse.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can be used to help explain why certain behaviors are more or less common in different cultures.

For example, individualism vs. collectivism can help explain why some cultures place more emphasis on personal achievement than others. Masculinity vs. feminism could help explain why some cultures are more competitive than others.

And long-term vs. short-term orientation can help explain why some cultures focus more on the future than the present (Hofstede, 2011).

International communication and negotiation

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can also be used to predict how people from different cultures will interact with each other.

For example, if two people from cultures with high levels of power distance meet, they may have difficulty communicating because they have different expectations about who should be in charge (Hofstede, 2011).

In Business

Finally, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can be used to help businesses adapt their products and marketing to different cultures.

For example, if a company wants to sell its products in a country with a high collectivism score, it may need to design its packaging and advertising to appeal to groups rather than individuals.

Within a business, Hofstede’s framework can also help managers to understand why their employees behave the way they do.

For example, if a manager is having difficulty getting her employees to work together as a team, she may need to take into account that her employees come from cultures with different levels of collectivism (Hofstede, 2011).

Evaluation

Although the cultural value dimensions identified by Hofstede and others are useful ways to think about culture and study cultural psychology, the theory has been chronically questioned and critiqued.

Most of this criticism has been directed at the methodology of Hofstede’s original study.

Orr and Hauser (2008) note Hofstede’s questionnaire was not originally designed to measure culture but workplace satisfaction. Indeed, many of the conclusions are based on a small number of responses.

Although Hofstede administered 117,000 questionnaires, he used the results from 40 countries, only six of which had more than 1000 respondents.

This has led critics to question the representativeness of the original sample.

Furthermore, Hofstede conducted this study using the employees of a multinational corporation, who — especially when the study was conducted in the 1960s and 1970s — were overwhelmingly highly educated, mostly male, and performed so-called “white collar” work (McSweeney, 2002).

Hofstede’s theory has also been criticized for promoting a static view of culture that does not respond to the influences or changes of other cultures.

For example, as Hamden-Turner and Trompenaars (1997) have envisioned, the cultural influence of Western powers such as the United States has likely influenced a tide of individualism in the notoriously collectivist Japanese culture.

Nonetheless, Hofstede’s theory still has a few enduring strengths. As McSweeney (2002) notes, Hofstede’s work has “stimulated a great deal of cross-cultural research and provided a useful framework for the comparative study of cultures” (p. 83).

Additionally, as Orr and Hauser (2008) point out, Hofstede’s dimensions have been found to be correlated with actual behavior in cross-cultural studies, suggesting that it does hold some validity.

All in all, as McSweeney (2002) points out, Hofstede’s theory is a useful starting point for cultural analysis, but there have been many additional and more methodologically rigorous advances made in the last several decades.

References

Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology. Oxford University Press, USA.

Hampden-Turner, C., & Trompenaars, F. (1997). Response to geert hofstede. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21 (1), 149.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International studies of management & organization, 10 (4), 15-41.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online readings in psychology and culture, 2 (1), 2307-0919.

Hofstede, G., & Minkov, M. (2010). Long-versus short-term orientation: new perspectives. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16(4), 493-504.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences (Vol. Sage): Beverly Hills, CA.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind. London, England: McGraw-Hill.

McSweeney, B. (2002). The essentials of scholarship: A reply to Geert Hofstede. Human Relations, 55( 11), 1363-1372.

Orr, L. M., & Hauser, W. J. (2008). A re-inquiry of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: A call for 21st century cross-cultural research. Marketing Management Journal, 18 (2), 1-19.

Hofstede's cultural dimensions theory is a framework for cross-cultural psychology, developed by Geert Hofstede. It shows the effects of a society's culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behavior, using a structure derived from factor analysis.

Hofstede's cultural dimensions theory - Wikipedia

**

普京的长桌:权力距离指数

普京的长桌:权力距离指数

两年前,普京在会见内阁官员时用的长桌,在网上吸引了大量的关注,一度成为网民们津津乐道的话题。其实,普京的长桌,非常生动形象地诠释了文化维度理论中的权力距离指数。

文化维度理论是是荷兰心理学家吉尔特·霍夫斯泰德提出的,用来解释不同国家文化差异的理论框架。他认为文化是在一个环境下人们共同拥有的心理程序,能将一群人与其他人区分开来。他通过因素分析,将不同文化间的差异归纳为六个基本的文化价值观维度,如下图所示:

权力距离指数(power distance index,缩写为PDI),指在政府、家庭、公司、社区等组织机构中地位较低的成员对于权力分配不平等的接受程度。在权力距离指数高的社会,地位较低的成员更倾向于服从地位较高的成员的命令,而同样的情形在指数低的社会,则需要合理化命令。简而言之,权利距离指数是指该文化中人们对权威或特权的接受程度。

高权力距离指数(High PDI)表明文化中能接受不公平和权力差异,接受官僚主义,并表现出对等级和权威的高度尊重。典型国家是:俄罗斯,中国、墨西哥、马来西亚等。这种文化下的具体表现包括:尊重权威和长者;接受权威、期待权威;更具依赖性;为社会地位而消费。

低权力距离指数(Low PDI)表明文化鼓励扁平的组织结构,具有分散的决策责任、参与式管理风格和强调权力分配的特点。典型国家是:英国、挪威、丹麦、芬兰等欧洲国家。这种文化下的具体表现包括:缩小不平等,反对权威论点;有批判性思维,尊重年轻观点;更具独立性;为实用性消费。

最初,人们对权力距离的研究大多集中于跨文化领域,并将其作为文化的一个维度进行阐述。现在,权力距离指数的研究已经广泛存在于管理学、市场学、政治学和社会学等领域。

有专家发现,权力距离指数和风险规避措施的有效性关系密切。具有高权力距离指数团体或企业,成员在表达自己观点时,往往使用一些极度含蓄的话,从而很难将情景准确地反映出来。当群体面对风险或危机时,下属往往忌惮于上级的权威,很难及时与上级沟通,或是在上报时使用一些较为含蓄词语,使上司很难准确或及时把握实际情况,从而延误风险诊断时间,给群体造成较大的经济损失。

譬如,1988年到1998年10年间,韩国航空飞机失事率为4.79架/百万次,相当于美国运联的17倍多。美国国家交通安全委员会将大韩航空后续发生的所有失事事件都记录备案。调查显示,大韩航空事故频发,跟飞机性能关系不大,而是飞机上的沟通机制出了问题。在他们的一次坠机事故前,黑匣子记录飞机曾发出了14次警铃,却仍然无法避免悲剧。事故很大程度上归咎于机师对机长权威的敬畏与服从。一方面,机师很难及时并且准确地向机长反映问题,并认为自己向机长提出解决选项是不合适的;另一方面,机师由于对机长权威的依赖必须等待机长给出明确的指令。类似情况是高权力距离国家国民的典型心态,这不仅会延误问题解决的最佳时机,也可能会对领导者的决策失误变本加厉。

只有当问题凸显在大众面前时,高权力距离国家才能在解决问题的效率上有所优势。但是,冰山位于水下的部分往往多于浮在水面的部分。因此,权力距离指数较高的情况下,不利于风险的及时规避。

权力距离指数高的国家,更容易滋生腐败。英国政治家阿克顿爵士有一句名言:“权力导致腐败,绝对的权力导致绝对的腐败”。

一方面,权力距离越大,对管理人员职权滥用的制约越少,腐败分子越是无所忌惮。有研究人员收集了18个发达国家的政府工作人员、企业领袖等的权力距离指数和腐败指数,发现二者有显著的正相关关系。反腐组织---透明国际发布的腐败指数中,76%的差异可以通过权力距离指数预测出来。

另一方面,权力距离指数越高越容易滋生行贿行为。对权力的追求和对权威的依赖,使权力拥有者成为社会资源的分配者,拥有较少权力的人为了追求更高的地位,倾向于抑制正常消费(除奢侈消费品外),节约资源用于对权力的追捧。研究统计了21个国家的行贿指数,结果和权力距离指数显著相关,行贿指数中45%的差异可以通过权力距离指数预测出来。

普京的长桌,形象地宣示俄罗斯是权力距离指数高高在上的国家。我推测,俄乌战争初期,俄军遭受的挫折,就和权力距离指数高有关。

还有,马来西亚是权力距离指数最高的国家,这是不是也导致了马航前些年出了好几起大事故?

附:各国及地区权力距离指数(从高到低排列,摘自网络,仅供参考):

马来西亚 104;危地马拉95;巴拿马 95;菲律宾 94;俄罗斯 93;墨西哥 81;委内瑞拉 81;中国 80;埃及 80;伊拉克 80;科威特 80;黎巴嫩 80;利比亚 80; 沙特阿拉伯 80; 阿拉伯联合酋长国 80;厄瓜多尔 78;印度尼西亚 78;加纳 77;印度 77;尼日利亚 77;塞拉利昂 77;新加坡 74;巴西 69;法国 68;香港 68;波兰 68;哥伦比亚 67;厄瓜多尔 66;土耳其 66;比利时 65;埃塞俄比亚 64;肯尼亚 64;秘鲁 64;坦桑尼亚 64;泰国 64;赞比亚 64;智利 63;葡萄牙 63;乌拉圭 61;希腊 60;韩国 60;伊朗 58;台湾 58;捷克共和国 57;西班牙 57;巴基斯坦 55;日本 54;意大利 50;阿根廷 49;南非 49;匈牙利 46;牙买加 45;美国 40;荷兰 38;澳大利亚 36;哥斯达黎加 35;德国 35;英国 35;瑞士 34;芬兰 33;挪威 31;瑞典 31;爱尔兰 28;新西兰 22;丹麦 18;以色列 13;奥地利11。

写于2024-06-12 蒙村

所有跟帖:

• 光是开会的,没有吃饭的:) -JSL2023- ![]() (0 bytes) (1 reads) 06/12/2024 postreply 20:56:12

(0 bytes) (1 reads) 06/12/2024 postreply 20:56:12

• 吃货本色,看见桌子就想到饭桌! -百里舟- ![]()

![]() (0 bytes) (1 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:25:25

(0 bytes) (1 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:25:25

• 赞!谢谢百里兄!涨知识学习了。中国得分高80,和好几个国家并列。-:)-:) -有言- ![]()

![]() (0 bytes) (2 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 03:56:38

(0 bytes) (2 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 03:56:38

• 中国的这个分数应该和传统的忠孝文化有关。谢谢鼓励! -百里舟- ![]()

![]() (0 bytes) (0 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:26:58

(0 bytes) (0 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:26:58

• 应该有一个权力距离指数与民航安全指数的对比,最好再加一个与腐败指数的对比。 -为人父- ![]()

![]() (126 bytes) (7 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 06:59:34

(126 bytes) (7 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 06:59:34

• 肯定有人作过这些对比,现在研究权力距离指数的文章和专著很多。我只知道一点皮毛。 -百里舟- ![]()

![]() (251 bytes) (5 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:34:14

(251 bytes) (5 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:34:14

• 不说权力 -PingFanCQ- ![]() (165 bytes) (44 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 07:52:50

(165 bytes) (44 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 07:52:50

• 是这个道理。谢谢点评! -百里舟- ![]()

![]() (156 bytes) (11 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:38:40

(156 bytes) (11 reads) 06/13/2024 postreply 09:38:40

已有5位网友点赞!查看