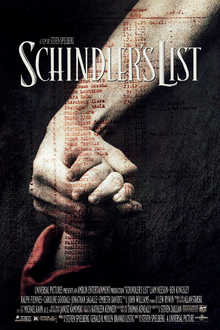

Schindler's List

Schinder's List (film)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Schindler's List is a 1993 biographical film directed by Steven Spielberg and written by Steven Zaillian, telling the story of Oskar Schindler, a German businessman who saved the lives of more than one thousand Polish Jews during the Holocaust. It was based on the novel Schindler's Ark by Thomas Keneally, and starred Liam Neeson as Schindler, Ralph Fiennes as Schutzstaffel officer Amon Göth, and Ben Kingsley as Schindler's accountant Itzhak Stern. The film was both a box office success and recipient of seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Score.

Plot

The film begins with the relocation of Polish Jews from surrounding areas to Krakow in late 1939, shortly after the beginning of World War II. Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), a successful businessman, arrives from Czechoslovakia in hopes of using the abundant cheap labour force of Jews to manufacture goods for the German military. Schindler, an opportunistic member of the Nazi Party, lavishes bribes upon the army and SS officials in charge of procurement. Sponsored by the military, Schindler acquires a factory for the production of army mess kits. Not knowing much about how to properly run such an enterprise, he gains a contact in Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), a functionary in the local Judenrat (Jewish Council) who has contacts with the now underground Jewish business community in the Ghetto. They loan him the money for the factory in return for a small share of products produced (for trade on the black market). Opening the factory, Schindler pleases the Nazis and enjoys his new-found wealth and status as "Herr Direktor," while Stern handles all administration. Stern suggests Schindler hire Jews instead of Poles because they cost less (the Jews themselves get nothing; the wages are paid to the Reich). Workers in Schindler's factory are allowed outside the ghetto though, and Stern falsifies documents to ensure that as many people as possible are deemed "essential" by the Nazi bureaucracy, which saves them from being transported to concentration camps, or even dying. Amon Göth (Ralph Fiennes) arrives in Krakow to initiate construction of a labor camp nearby, Płaszów. The SS soon clears the Krakow ghetto, sending in hundreds of troops to empty the cramped rooms and shoot anyone who protests, is uncooperative, elderly or infirmed, or for no reason at all. Schindler watches the massacre from the hills overlooking the area, and is profoundly affected. He nevertheless is careful to befriend Göth and, through Stern's attention to bribery, he continues to enjoy the SS's support and protection. The camp is built outside the city at Płaszów. During this time, Schindler bribes Göth into allowing him to build a sub-camp for his workers, with the motive of keeping them safe from the depredations of the guards. Eventually, an order arrives from Berlin commanding Göth to exhume and destroy all bodies of those killed in the Krakow Ghetto, dismantle Płaszów, and to ship the remaining Jews to Auschwitz. Schindler prevails upon Göth to let him keep "his" workers, so that he can move them to a factory in his old home of Zwittau-Brinnlitz, in Moravia, away from the "final solution", now fully underway in occupied Poland. Göth acquiesces, charging a certain amount for each worker. Schindler and Stern assemble a list of workers that should keep them off the trains to Auschwitz. "Schindler's List" comprises these "skilled" inmates, and for many of those in Płaszów camp, being included means the difference between life and death. Almost all of the people on Schindler's list arrive safely at the new site, with exception to the train carrying the women and the children, which is accidentally redirected to Auschwitz. There, the women are directed to what they believe is a gas chamber; but they see only water falling from the showers. The day after, the women are shown waiting in line for work. In the meantime, Schindler had rushed immediately to Auschwitz to solve the problem and to get the women off from Auschwitz; to this aim he bribes the camp commander, Rudolf Höß with a cache of diamonds so that he is able to spare all the women and the children. However, a last problem arises just when all the women are boarding the train because several SS officers attempt to hold some children back and prevent them from leaving. So Schindler, who is there to personally oversee the boarding, steps in and is successful in obtaining from the officers the release of the children. Once the Schindler women arrive in Zwittau-Brinnlitz, Schindler institutes firm controls on the Nazi guards assigned to the factory, permits the Jews to observe the Sabbath, and spends much of his fortune bribing Nazi officials. In his home town, he surprises his wife while she's in church during mass, and tells her that she is the only woman in his life (despite having been shown previously to be a womanizer). She goes with him to the factory to assist him. He runs out of money just as the German army surrenders, ending the war in Europe. As a German Nazi and self-described "profiteer of slave labor", Schindler must flee the oncoming Soviet Red Army. After dismissing the Nazi guards to return to their families, he packs a car in the night, and bids farewell to his workers. They give him a letter explaining he is not a criminal to them, together with a ring engraved with the Talmudic quotation, "He who saves the life of one man, saves the world entire." Schindler is touched but deeply distraught, feeling he could've done more to save many more lives. He leaves with his wife during the night. The Schindler Jews, having slept outside the factory gates through the night, are awakened by sunlight the next morning. A Soviet dragoon arrives and announces to the Jews that they have been liberated by the Red Army. The Jews walk to a nearby town in search of food. As they walk abreast, the frame changes to another of the Schindler Jews in the present day at the grave of Oskar Schindler in Israel. The film ends by showing a procession of now-aged Jews who worked in Schindler's factory, each of whom reverently sets a stone on his grave. The actors portraying the major characters walk hand-in-hand with the people they portrayed, also placing stones on Schindler's grave as they pass. We learn that the survivors and descendants of the approximately 1,100 Jews sheltered by Schindler now number over 6,000. The Jewish population of Poland, once numbering in the millions, was at the time of the film's release approximately 4,000. In the final scene, a man (Neeson himself, though his face is not visible) places a pair of roses on the grave, and stands contemplatively over it.

Production

Development Poldek Pfefferberg was one of the Schindlerjuden, and made it his life's mission to tell the story of his savior. Pfefferberg attempted to produce a biopic of Oskar Schindler with MGM in 1963,[1] with Howard Koch writing,[2] but the deal fell through. In 1982, Thomas Keneally published Schindler's Ark, which he wrote after he met Pfefferberg. MCA president Sid Sheinberg sent director Steven Spielberg a New York Times review of the book. Spielberg was astounded by the story of Oskar Schindler, jokingly asking if it was true. Spielberg "was drawn to the paradoxical nature of [Schindler]... It was about a Nazi saving Jews... What would drive a man like this to suddenly take everything he had earned and put it in all the service of saving these lives?" Spielberg expressed enough interest for Universal Studios to buy the rights to the novel, and in early 1983 Spielberg met with Pfefferberg. Pfefferberg asked Spielberg, "Please, when are you starting?" Spielberg replied, "Ten years from now."[1] Spielberg was unsure of his own maturity in making a film about the Holocaust, and the project remained "on [his] guilty conscience". Spielberg attempted to pass off the project to director Roman Polanski, but Polanski turned down the project, finding the subject matter too sensitive because his mother was gassed at Auschwitz,[3] and from his own personal experiences in (and his eventual survival of) the Kraków Ghetto. Spielberg also offered the film to Sydney Pollack.[2] Martin Scorsese was attached to direct Schindler's List in 1988. However, Spielberg was unsure of letting Scorsese direct Schindler's List, as "I'd given away a chance to do something for my children and family about the Holocaust." Spielberg offered him to direct the Cape Fear remake instead.[2] Billy Wilder also expressed interest in directing the film, "as a memorial to most of [his] family, who went to Auschwitz." Spielberg finally decided to direct the film, after hearing of the Bosnian genocide and various Holocaust deniers.[1] Spielberg stated that with the rise of neo-nazism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, people were once again tolerating intolerance, as they did in the 1930s. In addition, Spielberg, who suffered Antisemitism as a child, was accepting his Jewish heritage while raising his children.[4] Sid Sheinberg greenlit the film on one condition: that Spielberg make Jurassic Park first. Spielberg later said, "He knew that once I had directed Schindler I wouldn't be able to do Jurassic Park".[2] Thomas Keneally was initially hired to adapt his book in 1983, and he turned in a 220-page script. Keneally focused on Schindler's numerous relationships, and admitted he did not compress the story enough. Spielberg hired Kurt Luedtke, who wrote Out of Africa, to write the next draft. Luedtke gave up almost four years later, as he found Schindler's change of heart too unbelievable. During his time as director, Scorsese hired Steve Zaillian to write the script. When he was handed back the project, Spielberg found Zaillian's 115-page draft too short, and asked him to extend it to 195 pages. Spielberg wanted to focus on the Jews in the story, and extended the ghetto liquidation sequence, as Spielberg "felt very strongly that the sequence had to be almost unwatchable." Spielberg also felt Schindler's transition had to be ambiguous, and not "some kind of explosive catharsis that would turn this into The Great Escape."[2]

Music

John Williams composed the score for Schindler's List. The composer was amazed by the film, and felt it would be too challenging. He said to Spielberg, "You need a better composer than I am for this film." Spielberg replied, "I know. But they're all dead!" Williams played the main theme on piano, and following Spielberg's suggestion, he hired Itzhak Perlman to perform it on the violin. In the scene where children are transported away on trucks, while their screaming mothers give chase, the folk song "Oyf'n Pripetshok" is sung by a children's choir. The song was often sung by Spielberg's grandmother, Becky, to her grandchildren.[11] References ^ a b c David Ansen; Abigail Kuflik. "Spielberg's obsession", Newsweek, pp. 112-116. ^ Susan Goldman Rubin (2001). Steven Spielberg. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 73-74. ISBN 0-8109-4492-8.

Retrieved from and for more: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schindler's_List

|

/>

|