维贾伊·普拉萨德 三大洲社会研究所 执行董事,印度记者、评论家https://blog.wenxuecity.com/myblog/72696/202204/21732.html

General overview of Tricontinental Institute for Social Research https://thetricontinental.org/general-overview/

Facebook: Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

https://business.facebook.com/thetricontinental/

We produce forward-thinking research in conjunction with movements across the Global South.

http://www.thetricontinental.org/

celina@thetricontinental.org

Work

Tricontinental proposes to be a fulcrum between political movements and academic production. We would like to cultivate closer ties between the agendas of political movements and intellectuals, and to stimulate debate in both the movements and in intellectual circles around issues of great importance for our times. To produce useful research and to stimulate important debates, we will produce materials that we hope will contribute to ongoing discussions and build a network of left-leaning intellectuals.

To read an interview with Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research Director Vijay Prashad and Red Pepper Magazine about our work, click here.

About VIJAY PRASHAD

Vijay Prashad is the author or editor of about thirty books, including The Darker Nations: A Biography of the Short-Lived Third World, and Washington Bullets. He is the Executive Director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, Chief Correspondent for Globetrotter, and Editor at LeftWord Books.

Articles of Vijay Prasad, director of Tricontinental Institute for Social Research

https://www.guancha.cn/VijayPrashad

为何欧美只关心乌克兰人,却对亚非人民的痛苦视而不见?

在所有给这个脆弱星球带来创伤的战争中,乌克兰战争只是其中一场。发生在非洲和亚洲的战争似乎连绵不绝,而对发生在亚非的某些战争,全世界的媒体却对其置若罔闻,社交平台上虽帖子无数可也对其鲜有评论。[全文]

我们的态度必须是,我们对西方正在发生的事情很感兴趣,但我们不能中了西方的毒,不能陶醉于西方。我们想要展望世界,向所有国家学习。对祖国的热爱并不意味着对别国的仇恨。你可以既爱国又不排外,但你爱的都是哪些国家呢?你必须打破自己对美国的迷恋。[全文]

你们只会居高临下,因为对你们来说,殖民主义不是已经被打败的“过去式”,对你们来说,殖民主义是永恒的。这种永恒的殖民主义通过两种方式进行,一种是永恒的殖民心态。你想对我们说教,你想告诉我们,我们才是一切问题的根源,因为你们永远不会接受错误,你们才是最应该负责的人。[全文]

农民落入了农业科技企业、科技巨头的手中,这些企业不会致力于解救气候灾难,而是会优先考虑大肆敛财,同时给自己的行为披上环保的外衣。这种对利益的渴求不会终止全球饥饿问题,也不会终结气候灾难。[全文]

医用氧气不足,而执政的印度人民党(BJP)却没有兑现承诺,扩大产能。印度政府一直在出口氧气,甚至在国内储备明显濒临枯竭的情况下也没有停止(印度还出口了珍贵的雷姆德西韦注射液)。[全文]

拉美与欧洲将是决定世界上支持冷战和反对冷战的力量之间斗争结果的主战场——在世界大多数地区,支持和反对的力量胜负已定。在这种情况下,中国对拉美发展大势高度关注非常重要。厄瓜多尔4月11日的总统选举,将是下一轮重要且“旷日持久”的斗争的前哨。[全文]

世界上大多数国家都面临一个选择:是选择中国提出的双赢模式,还是美国主张的臣服于美国,与它一同反华的经济毁灭性道路?美国一直将拉美视为自己的“后院”,然而越来越多的国家在寻求国家独立,少数国家在寻求社会主义发展道路。[全文]

正是为了阻止中国的技术进步,美国动用了各种手段,既施加外交压力又施加军事压力,但这些手段似乎都没有奏效。目前,中国的态度很坚决。它不愿意让步自毁其技术成果。[全文]

2020-09-01 07:31:50

印度学者维贾伊·普拉萨德当面嘲讽西方国家:这像话吗?

https://www.sohu.com/a/510843952_115479

【视频/维贾伊·普拉萨德】, 2021-12-23 08:17

首先,我想说感谢“强迫”我来到格拉斯哥,格拉斯哥是英国第二重要的城市,每当我走在格拉斯哥这种城市的街道上时,那些漂亮的建筑和街道,这是一个美丽的城市。

1919年,格拉斯哥经历了“红色克莱德赛德”(Red Clydeside)工人运动——一场试图在苏格兰建立苏维埃政权的起义(左派号召罢工反战)。当然,这场运动失败了(组织者没有寻求革命,结果被捕和被镇压)。当我看到格拉斯哥这样的城市时,我还会想到这些城市的另一面。

瓦尔特·本雅明曾说过,“文明的丰碑就是野蛮暴力的实录”,我想到孟加拉的饥荒,而孟加拉的工人,通过格拉斯哥港口将货物送往敦提(英国苏格兰东部港口城市)。我想到非洲的人们被奴役,从加纳运到“新大陆”,所有这些获得的利益,都被吸进伦敦和格拉斯哥等城市。

在1765年至1938年之间,英国从印度偷了45万亿英镑,当英国人离开印度的时候,我们没有获得报酬。当我们把英国人赶出去时,我们的识字率只有13%,几百年所谓的“文明”也不过如此。

与此同时,我们的风景被摧毁,煤炭被强加在印度身上,是你们把煤炭强加在我们身上,让我们变得如此依赖煤炭,然后你们拍拍屁股走人。而现在你们竟敢居高临下地对待我们,当我听到英国首相约翰逊的讲话、当我听到美国总统拜登讲话、更别说当我听到法国总统马克龙(提议谁排放最多,谁责任大)的讲话时,我只能想到你们是多么的居高临下。

400年前,你们居高临下地对待我们;300年前,你们居高临下地对待我们;200年前,你们居高临下地对待我们;100年前,你们居高临下地对待我们;直到今天,你们还在居高临下地对待我们。

你们只会居高临下,因为对你们来说,殖民主义不是已经被打败的“过去式”,对你们来说,殖民主义是永恒的。这种永恒的殖民主义通过两种方式进行,一种是永恒的殖民心态。你想对我们说教,你想告诉我们,我们才是一切问题的根源,因为你们永远不会接受错误,你们才是最应该负责的人。

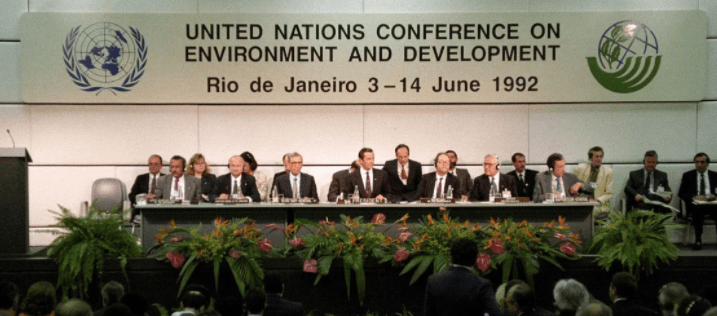

1992年,你们在里约的地球高峰会(Earth Summit)上签署了“共同但有区别的责任”原则,你们喜欢说同舟共济,但我们可没有同舟共济的情谊,美国人口只有世界人口的4%至5%,却消耗了世界四分之一的资源(绝大部分是稀有军工资源),你们将制造业转移给中国,然后说中国“碳污染”。

1992年,里约热内卢举行的地球高峰会上,155个国家签署了《联合国气候变化框架公约》。来源:维基百科

而中国正在生产你们的水桶,中国正在生产你们的螺母和螺栓,中国正在生产你们的手机,试试在你们自己的国家生产,然后看着你们的碳排放量增加成什么样。你们太喜欢说教,因为你们有殖民心态、殖民结构和机构,你每次贷款给我们的钱,那还都是我们的钱!

国际货币基金组织每次来到我们的社会告诉我们:“这是我们给你的钱。”不!那明明是我们的钱,你把我们的钱以债务的形式放还给我们,还对我们的生活方式指手画脚,这简直离谱。

这不仅仅是殖民心态,而且还是殖民结构和机构,并且永无止境地、年复一年地自我复制。气候正义运动(1999年发起,要求殖民国家正视历史责任和生态债务)对这些问题的理解还不够明确,气候正义运动说:“我们担心人类的未来。”什么未来?非洲、亚洲、拉丁美洲的那些孩子们没有未来可言,他们甚至没有现在,他们担心的不是未来,他们担心的是现在,你们的口号却是“我们担心未来”。

这是西方中产阶级的口号,你们必须担心现在,全球有27亿人吃不上饭,你却告诉他们要减少消耗?这对于一个几天没吃上饭的孩子来说像话吗?你们必须好好想想,否则这些气候正义运动将在第三世界国家毫无立足之地。

稍后我将介绍国际人民大会(该组织力求推进跨国工人国际主义,反帝反殖民),一个深深扎根在全球南方国家,由200个政治组织组成的网络,我们愿意告诉你们所面对的问题是什么,但你们愿意听吗?

专访之前愤怒指责西方的印度学者维贾伊·普拉沙德:西方并不完美,无权说教

来源:环球时报作者:白云怡; 2021-12-28

https://world.huanqiu.com/article/46A93WauHIN

【环球时报记者 白云怡】在《联合国气候变化框架公约》第26次缔约方大会(COP26)一段5分钟的“愤怒宣言”中,印度马克思主义学者维贾伊·普拉沙德痛斥西方“永恒的殖民心态和殖民结构”,在发展中国家引起强烈共鸣。这段大快人心的视频,配上不同语言的字幕,在国内外社交媒体上被大量转发。敢于当面“硬刚”西方,说出发展中国家民众内心真实不满的维贾伊24日接受了《环球时报》记者专访。他表示,发表“愤怒宣言”的导火索是由于几名石油公司高管对莫桑比克天然气田附近穷苦人民的无视。西方国家一直宣称他们拥有人权和民主的全部答案,但现在,有太多人对西方主导的国际秩序感到失望。

维贾伊(右二)在COP26上发言。

维贾伊(右二)在COP26上发言。

“格拉斯哥街头几个石油公司高管的话,成了‘愤怒宣言’的导火索”

环球时报:你当时为什么去格拉斯哥,并发表了那样一篇“愤怒的宣言”?有没有什么幕后故事?

维贾伊:发表那番演讲的早晨,我正在英国的格拉斯哥当地一个核酸检测点排队,几名石油公司的高管排在我身后。其中一个人看到我戴着参加大会的媒体通行证,就问我:“你在这里做什么?”于是我对他们讲述了一段我在莫桑比克的经历。

我曾报道过一条新闻,内容涉及在莫桑比克的两家石油公司,一家是法国的道达尔(Total),另一家是美国的埃克森美孚(Exxon Mobil)。他们在莫桑比克发现并开发了一个巨大的天然气田。2017年,在莫桑比克最贫穷的省份——德尔加杜角省,人们发起了暴动。

参与暴动的人说:“我们太穷了,我们亲眼看到了天然气的开发,但我们没有从中得到任何好处。”总之,当地人的不满情绪很高。法国和美国的军队一度想过出手干预莫桑比克的局面,不过他们最终没这么做。后来,他们和卢旺达军队达成一项协议,卢旺达军队到莫桑比克镇压了暴动。(编者注:莫桑比克政府认为,这场暴动是由当地伊斯兰极端主义者发起的。今年7月,卢旺达宣布应莫桑比克要求,将一支1000人的特遣队部署至德尔加杜角省,协助应对当地叛乱。外交消息人士认为,这是多方妥协的结果。)对这件事,我一直非常难过。

我告诉那几位石油公司高管,看到穷困的莫桑比克人生活在天然气田的附近,却连肚子都填不饱,这让我很不安,我要在会议上说一说类似这样的事情。然而,接下来他对我说的一番话,成为引发我那篇演讲的直接“导火索”。

他对我说:“你说的都对,但没有人会在乎。你没有撒谎,你说的所有事情都是正确的,可是,谁也不会关心那些在德尔加杜角的人。”他的话让我十分恼火。于是,当我返回会场后,轮到我发言时,我内心深处响起了一个声音:“好吧,如果没人关心,那我也不管了,我要把我真正想说的都说出来。”

环球时报:你的这段发言在中国的社交网络上引发了很多讨论,对此你有何感受?这段演讲在其他国家的反响怎么样?

维贾伊:你们看到的视频其实是我在格拉斯哥几场发言中的一小段。事实上,它不仅在中国社交网络上成了“爆款”,在印度、非洲、拉美和加勒比地区都被配上了字幕广为传播。

不久前,我去了委内瑞拉的一个公社,公社负责人是一名妇女,她突然走到我面前说,“啊,你就是那个在气候变化峰会上发言的家伙!”我当时的第一感觉是,“天啊,我活了54岁了,我的一生要被这短短5分钟的视频给定义了!”

坦率地说,我(对这段视频的广泛传播)感到特别振奋,原来有这么多不同背景的人都关注着这样一件我认为很重要的事情——(今天仍然存在的)殖民结构和殖民心态。

一个事物在网络上成为爆款,往往不是因为我们说了什么新奇的东西,而是因为我们说出了很多人心里已经在想的事情。这件事给我的感觉是,已经有太多人对现在的国际秩序感到挫败沮丧。我们想要改变。

“他们拥有一切问题的答案”的感觉让许多人不爽很久了

环球时报:正如你所说,一段话在社交媒体上能“火”起来,往往是因为它击中了很多人内心潜藏的情感。在你看来,人们对西方国家的愤怒因何而来?

维贾伊:我想,那是因为我们已经受够了被来自华盛顿、伦敦、巴黎的领导人说教,告诉我们应该做什么,不该做什么。他们声称,他们做得比我们好,他们拥有人权和民主的所有答案,他们在所有事情上都是最好的裁判。这种态度特别让人感到沮丧。

看看吧,美国才是世界上监禁率最高的国家。这一点每个人都知道,它被写在几乎所有的报告里。那为什么他们却不停地向别的国家进行人权说教?没有国家是完美的,让我们直面这一点。

事实上,我们都在努力变得更好,我们也必须改进很多现实情况。但是,西方的说教总给人一种“他们拥有一切问题的答案”的感觉,我觉得这是许多人感到不爽的原因,而且这种不爽已经很久了。

环球时报:你在大会发言中认为,对很多西方发达国家来说,殖民主义不是已经被打败的“过去式”,对他们来说,殖民主义是永恒的。

这种永恒的殖民主义通过两种方式进行,一种是永恒的殖民心态,一种是殖民结构和机构。为什么你认为今天西方国家对发展中国家的态度和19世纪并无二致?

维贾伊:坦率地说,要西方国家摆脱殖民心态非常困难。这就好像男权思想一样,过去几百年中,在很多社会里,男人很自然地认为自己天生比女人高贵,让他们意识到男尊女卑是一个疯狂的想法需要很长时间。

西方的殖民心态也是一样。殖民主义距今已存在了五六百年,在过去的五百多年中,他们一直把我们视为低等人,可以随便欺负我们,命令我们去做这做那。

比如在中国,曾经发生过鸦片战争,(英国人更习惯把叫它)英中战争。但是,中国的舰队没有跑到英国去挑起一场战争,中国人没有去轰炸英格兰,叫它英中战争是错的。没有什么英中战争,只有一场英国强加给中国的战争。

西方需要承认自己的殖民历史。现在的他们对此仿佛失忆了一般,法国、英国、美国,从来没有人承认自己的过去。比如,英国说对在香港发生的事情感到非常不安,但麻烦请记住:在香港处于英国殖民统治的时候,那里完全没有民主。他们为什么不承认这一点?最后一任港督彭定康在香港时,香港人有什么民主?现在他们居然对中国人说教,这实在太有趣了。他们甚至意识不到自己的历史。

在印度也是一样。英国人直接统治了印度两百年,完全没有什么民主。当英国人离开印度时,只有13%的印度人识字。所以,不要对我们的政府说教。

总之,西方对我们的态度,就好像我们还是小孩,他们必须扇我们的耳光,告诉我们要规规矩矩的。这是一个长期的事情,不是一个能短期解决的问题。

“想知道在印度做一个马克思主义者是一种怎样的体验?问问印度农民吧”

环球时报:你是一个研究马克思主义和社会主义的学者。能否告诉我们,在印度做一个马克思主义者是一种怎样的体验?

维贾伊:印度有很长的马克思主义传统,印度的共产党建立于1920年。印度今天还有几个不同的共产主义政党,其中最大的是印共(马派),有100多万名党员。

我从很小的时候就已经开始阅读马克思的著作。你可以看到,我的书架上有很多有关社会主义的书,许多是我从苏联买来的。1981年我还是个小男孩时,我在加尔各答买了三卷《资本论》。很多和我同时代的青年也都阅读过马克思主义的书籍。

然而,后来我们经历了苏联的解体,这一事件让我们有那么一段时间感觉自己被击败了。从此以后,做一个马克思主义者要面临很多压力。

现在,在印度做一个社会主义者并不是一件容易的事,因为印度政府倾向于用宗教的视角来处理政治问题。我对此十分不赞同。

与此同时,今年数百万印度农民在全国举行示威,反对政府强加给他们的农业改革法案,这些法案会让农民(失去土地)变成Uber司机。(编者注:印度农业改革将允许大型私有企业进入农产品销售市场,并允许商家囤积食品,被印度农民视为违背农民利益,引发强烈不满。)

很难想象,在新冠疫情肆虐的这一年,我们竟然经历了世界上最大、最有力量的群众运动之一,而且最终政府撤回了这些法案,也就是说农民取得了胜利。他们展现的正是马克思主义的活力。想知道在印度做一个马克思主义者是什么感觉?那就去问一问印度的农民吧。

环球时报:你认为今天的印度需要社会主义吗?

维贾伊:作为普通人,我们最想要的是什么?我想生活在这样一个社会:人们没有饥饿,也不是文盲,每个人都有地方可以居住,可以接受更好的教育,有电、有互联网和其他便利的设施。然而,直到今天,上千万甚至上亿的印度人还没法过上这样的生活。

如果资本主义可以为他们提供这样的生活,我会变成一个资本主义者,但资本主义做不到这一点。只有社会主义才可以让每个人都不再挨饿。

事实上,我们已经在“中国实验”中看到它实现了——我现在经常使用“中国实验”这个词,因为你们在尝试很多不同的东西。我非常欣赏这一点。

今年,当我读到中国消除绝对贫困的消息时,真的很开心,因为这意味着农民终于可以吃上饱饭了。我觉得尝试消除绝对贫困的行动也许是在很长一段时间内这个世界上发生的最重要的事情,因为它向印度这样的国家证明,哪怕是穷一点的国家也可以做到这些事。

我不是中国人,但是我为中国政府所做的事情而感到骄傲。这正是国际主义的意义所在,印度需要社会主义。在印度搞社会主义容易吗?不容易。在美国搞社会主义容易吗?不容易。它将非常困难,但值得我们为之努力。

环球时报:感谢你对中国的赞赏。不过,我们也看到,最近两年来中印因边界问题关系非常紧张。还有一些印度政治人物和学者更视中国为“敌人”,主张联合华盛顿制衡中国。你怎么看这种观点和当下的中印关系?

维贾伊:印中现在是“没必要的紧张关系”。我不认为边界争议很重要,别忘了,就在十多年前,中国和俄罗斯还存在边界争议。边界问题是可以解决的,重要的是潜在的政治问题,这才是关键。

当下,印度的精英阶层对和美国结盟更感兴趣,但这实际上对印度民众没有好处。印度应该做的是融入到“亚洲世纪”里。我们为什么要把“一带一路”想象成一个“中国计划”呢?我们应当把它视为一个亚洲的计划。印度应该积极地参与到对基础设施的投资中。

一些印度的精英阶层认为,通往自由的道路必须从华盛顿经过。但我希望印度的治国精英们能够对商业和人类自由都抱以更开放的思想,印度是一个伟大的国家,我们没必要向任何一方“选边站”。

Vijay Prashad Photo:Global Times

What made Prashad deliver such a speech in Glasgow? What is the essence of Western countries' behavior in his eyes? Why did he say India needs socialism today? And what is his understanding of China and India's relationship? Recently, the Global Times (GT) reporter Bai Yunyi conversed with Prashad (Prashad) to learn more about his experience and thoughts on such issues.What really matters

GT: What made you go to Glasgow and deliver that speech at the COP26 conference? Could you share more behind-the-scenes details with us?

Prashad: I had reported a story in Mozambique about oil companies. One is a French company, Total; while the other is an US company, Exxon Mobil. They have found the biggest offshore oilfield and a natural gas field in Mozambique, Africa.

People who lived just off the field in Cabo Delgado, which is the poorest province in Mozambique, started an uprising in 2017. They insisted that, "we are so poor. We can see this natural gas development. We are getting no benefit." They were upset. The French and American armies were to intervene. They didn't, but struck a deal with the Rwandan army which went in and crushed the uprising. I was very sad about this.

So that morning in Glasgow, I was in the queue to get a PCR test. There were some oil company executives behind me. One of them saw my press pass. He said, "What are you doing here?" So I told him the Mozambican story.

I said that I have seen poor people in the shadow of a natural gas field who will not even be able to eat. This upset me, so I had to come and talk about things of that nature.

But he said something to me that triggered that speech. He said, "You are right. But nobody cares. You're not lying. You're not wrong. Everything you say is correct, but nobody cares. They don't care about those people in Cabo Delgado."

That got me a little annoyed. And I have to tell you honestly, when I went back into the session, and they gave me my turn to speak, I thought, "I'm going to just say what I believe."

GT: Your speech at the COP26 went viral on Chinese social media. Did you receive any feedback from your Chinese counterparts? All things considered, how do you feel about the speech in hindsight?

Prashad: The truth is that this little segment you see is from a number of speeches that I made in Glasgow, which have gone viral everywhere including in India, on the African continent, in the Caribbean, and in Latin America with the use of subtitles.

I went into a community in Venezuela. And a woman who is the leader of the community said to me, "You're the climate change guy." I thought "Goodness, I'm 54 years old. I've done a lot of things in my life, and I'm going to be defined by this five-minute clip."

It's very exciting, to be honest, that so many different kinds of people are engaging with what I think is really important - the colonial structures and a neo-colonial mentality.

It's not that I said something new, but that it was a matter of what people are already thinking. And it leads me to feel that lots of people are frustrated with the current world order. And we want something different.

Arrogant 'lecturers'

A woman carries her child on her back while selling goods on the street in Luanda, capital of Angola, on October 19, 2021. Luanda is considered one of the oldest colonial cities on the African continent. Photo:IC

GT: As you said, a segment went viral on social media because it was a matter of what people are already thinking. What do you think the reason for the anger toward the West is? Why do so many people feel frustrated by the current world order?Prashad: I think that [is because] we are fed up with being told what to do by leaders from Washington, London, and Paris, who claim to be in a way better than we are. They claim they are the best judges of everything and have all the answers to human rights and democracy. Their attitude is very frustrating to people.

Consider this: The US has the highest per capita incarceration rate in the world. Why do they still keep lecturing everybody else about human rights?

We're all struggling to make better things happen. But they "lecture" us as if they have all the answers, and I think [that's why people] have been frustrated for such a long time.

GT: You also talked about the "permanent colonial mentality" of West in your speech. Where do you think their colonial mentality comes from? Why do you think Westerners' attitudes toward developing countries today are still the same as they were in the 19th century?

Prashad: Let's be frank. It's very difficult to get rid of the West's colonial mentality. It's like patriarchal mentality: Over the centuries and in many societies, men have thought they are superior to women. It has taken a long time to teach men that believing that women are inferior to men is a crazy idea. Similarly, it is going to take a long time to transform Westerners' colonial mindset, which has been there for five or six hundred years. For over 500 years, they thought that we are lesser people. They therefore think they can go and bully us, telling us what to do.

In China there was the Opium Wars in the 19th century, which the British tend to call "Anglo-Chinese Wars." However, the Chinese ships didn't go and start a war in England, and the Chinese did not bombard England. They were the wars that the British imposed upon China. These were no "Anglo-Chinese" wars but British wars.

I always get annoyed when Westerners say "the Vietnam war." There was no "Vietnam war" but a US war imposed upon Vietnam. There's no Iraq war but another US war imposed upon Iraq. It's very hard to get this attitude out of their heads.

The West needs to recognize the history of colonialism. But they seemed to have amnesia about this - France, the UK, and the US - nobody ever accepts their past. The British, for instance, are currently very upset about what's happening in Hong Kong. But remember, the British held Hong Kong as a colony. There was no democracy there under British rule. Why don't they recognize that? When Chris Patten was the last governor of Hong Kong as a British colony, what democracy was there for Hong Kong people? And yet they are busy lecturing the Chinese, which sounds very interesting to me. They don't even possess self-awareness about their own history.

The British directly ruled India for at least 200 years, during which time there was no democracy. When the British left India, only 13 percent of the Indian population was literate. So now don't lecture us about our government.

The West's attitude toward us is that of infantilization. They feel they have to cajole us to make us behave. It's a long-term issue, and one that's going to take time to purge such attitudes from Western thinking.

India needs socialism

GT: You are a Marxism and socialism scholar. Can you tell us what it is like to be a Marxist in India?

Prashad:India has a very long communist tradition. There are several communist parties in India. The largest communist party is the Communist Party of India, which has more than 1 million members. Until recently, Marxism was one of the dominant forms of thought in India. Especially in the field of economics, Marxism held its own.

I have been reading Marx's works since long ago. As you can see, I have many books on socialism on my shelves, many of which I bought from the Soviet Union. When I was a little boy in 1981, like many of my contemporaries, I bought three volumes of Capital in Calcutta.

However, then we were faced with the collapse of the Soviet Union, an event that made us feel defeated for a while, and since then, there has been a lot of pressure to be a Marxist. To be honest, things are not easy in India for socialism today, because the government has a certain sort of religious perspective, regarding politics. I'm not in favor of religion in politics.

However, this year, millions of farmers in India held protests against farm reform bills. In a way the farmers showed the vitality of Marxism because this was authentic class struggle.

Indian activists and farmers try to stop a train at a railway station in Kolkata to protest against the central government's agricultural reforms on September 27, 2021. Photo: AFP

It has been a very powerful year amid the COVID-19 pandemic. We had one of the world's largest mass movements in which the government had to repeal its laws. That means the farmers won. If you want to know what it feels like to be a Marxist in India, ask the people who has walked among the farmers.

GT:Do you think today's India needs socialism?

Prashad: What do we want as ordinary people? I want to live in a society where people are not hungry or illiterate, where people have shelter and access to high quality education, and access to the internet and electricity. But today, hundreds of millions of Indians don't have these things. If capitalism can provide them such living conditions, I would become a capitalist, but capitalism cannot do it. Only socialism can lift everybody up from the brink of starvation. We see that it has actually been done in the "Chinese experiment"— I use the term "Chinese experiment" a lot because innovative Chinese people are constantly trying different things. I really appreciate that.

I think that China's attempt to eradicate poverty is probably the most important thing that's happened in a long time in the world, because it showed countries like India it can be done in a poor country.

I'm not Chinese, but I am proud of what the Chinese government has done. I think socialism is necessary in India. Is it easy to make socialism in India? No. Is it easy to make socialism in the US? No. It's going to be very difficult, but it worth the struggle.

GT: Some Indian politicians and scholars see China as a big threat. They think India should stand with the US to confront China because of current border tensions between China and India. What is your view on this perspective?

Prashad: I don't think the current border tensions are important. China had a border dispute with the USSR that was only resolved 10 years ago. And today, Russia and China have one of the closest global relationships. Border disputes can be solved. It's the underlying political problems that are important.

Right now, the Indian elites are more interested in an alliance with the US. This is actually bad for the people of India, because India needs to get involved in the "Asian era."

Why should we imagine the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) as being solely a Chinese project? We have to imagine BRI as being an Asian project. India needs to also be involved in this investment in infrastructure and so on.

The elites, however, feel that the road to freedom comes through Washington. I think India needs to have a non-aligned foreign policy. India should take a neutral position. India is a great country and doesn't have to be in anybody's camp. Indian ruling elites should have a more open-minded attitude toward business, commerce, and human freedom.

Book:

Washington Bullets

https://mayday.leftword.com/catalog/product/view/id/21820

LeftWord Books, New Delhi, 2020

“Like his hero Eduardo Galeano, Vijay Prashad makes the telling of the truth lovable; not an easy trick to pull off, he does it effortlessly.” — Roger Waters, Pink Floyd

“This book brings to mind the infinite instances in which Washington Bullets have shattered hope.” — Evo Morales Ayma, former President of Bolivia

Washington Bullets is written in the best traditions of Marxist journalism and history-writing. It is a book of fluent and readable stories, full of detail about US imperialism, but never letting the minutiae obscure the larger political point. It is a book that could easily have been a song of despair – a lament of lost causes; it is, after all, a roll call of butchers and assassins; of plots against people’s movements and governments; of the assassinations of socialists, Marxists, communists all over the Third World by the country where liberty is a statue.

Despite all this, Washington Bullets is a book about possibilities, about hope, about genuine heroes. One such is Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso – also assassinated – who said: ‘You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future. It took the madmen of yesterday for us to be able to act with extreme clarity today. I want to be one of those madmen. We must dare to invent the future.’

Washington Bullets is a book infused with this madness, the madness that dares to invent the future.

Contents

Preface by Evo Morales Ayma 9

Files 13

‘Bring Down More US Aircraft’ 17

Part 1

Divine Right 23

Preponderant Power 24

Trusteeship 26

‘International Law Has to

Treat Natives as Uncivilized’ 28

‘Savage Tribes Do Not Conform

to the Codes of Civilized Warfare’ 31

Natives and the Universal 34

UN Charter 36

‘I am for America’ 39

Solidarity with the United States

against Communism 42

‘No Communist in Gov. or Else’ 45

‘Nothing Can Be Allowed’ 48

Third World Project 51

Expose the US ‘Unnecessarily’ 53

Part 2

Manual for Regime Change 65

Production of Amnesia 90

‘Be a Patriot, Kill a Priest’ 93

8

Contents

The Answer to Communism

Lay in the Hope of Muslim Revival 96

‘I Strongly Urge You to Make This a Turning Point’ 100

‘The Sheet is Too Short’ 106

The Debt of Blood 109

All the Cameras Have Left For the Next War 111

Part 3

‘Our Strategy Must Now Refocus’ 115

‘Rising Powers Create Instability

in the International State System’ 119

‘Pave the Whole Country’ 122

Banks Not Tanks 125

First Amongst Equals 128

Only One Member of the Permanent

Security Council – the United States 130

Republic of NGOs 132

Maximum Pressure 135

Accelerate the Chaos 140

Sanctions are a Crime 142

Law as a Weapon of War 146

Dynamite in the Streets 148

We Believe in People and Life 152

Sources 155

Acknowledgements 161

9

Preface

This is a book about bullets, says the author. Bullets that assassinated democratic processes, that assassinated revolutions, and that assassinated hope.

The courageous Indian historian and journalist Vijay Prashad has put his all into explaining and providing a digestible and comprehensive way of understanding the sinister interest with which imperialism intervenes in countries that attempt to build their own destiny.

In the pages of this book, Prashad documents the participation of the United States in the assassination of social leaders in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, and in the massacres of the people, who have refused to subsidize the delirious business dealings of

multinational corporations with their poverty.

Prashad says that these Washington Bullets have a price: ‘The biggest price is paid by the people. For in these assassinations, these murders, this violence of intimidation, it is the people who lose their leaders in their localities. A peasant leader, a trade-union

leader, a leader of the poor.’ Prashad provides a thorough account of how the CIA

participated in the 1954 coup d’état against the democratically elected president of Guatemala, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. Árbenz had the intolerable audacity of opposing the interests of the United Fruit Company.

In Chile, Prashad shows us how the US government spent $8 million to finance strikes and protests against Allende.

What happened in Brazil when the parliamentary coup removed president Dilma Rousseff from office in August 2016 is an example of the perverse practice of ‘lawfare’, or the ‘use of law as a weapon of war’. The same method was used against former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who suffered in prison for 580 days as a result of a trial in which the prosecutors did not provide concrete evidence – just ‘firm beliefs’.

Times have changed, and business is no longer carried out in the same way, but the underlying methods and responses of imperialism have remained largely unaltered.

Bolivians know this perverse politics well. Long before our fourteen years at the head of the Plurinational State of Bolivia, we have had to confront the operations, threats, and retaliation of the United States.

In 2008, I had to expel Philip Goldberg, the ambassador of the United States, who was conspiring with separatist leaders, giving them instructions and resources to divide Bolivia. In that moment, the US Department of State said that my claims were unfounded.

I don’t know what they would say now, when the participation of the US embassy in the coup that overthrew us at the end of 2019 is so clear. What will future researchers say who take up the work of reading the CIA documents that are classified today?

The Monroe Doctrine and the National Security Doctrine attempt to convert Latin America into the United States’s backyard and criminalize any type of organization that opposes its interest and that attempts to build an alternative political, economic, and social model.

Over the decades, the US has invented a series of pretexts andhas built a narrative to attempt to justify its criminal political and military interventions. First, there was the justification of the fight against communism, followed by the fight against drug trafficking, and, now, the fight against terrorism.

This book brings to mind the infinite instances in which Washington Bullets have shattered hope. Colonialism has always used the idea of progress in accordance with its own parameters and its own reality. This same colonialism – which puts our planet in a state of crisis today, devours natural resources, and concentrates wealth that is generated from devastation – says that our laws of vivir bien [‘living well’] are utopian. But if our dreams of equilibrium with Pachamama [‘Mother Earth’], of freedom,and of social justice are not yet a reality, or if they have been cut short, it is primarily because imperialism has set out to interfere in our political, cultural, and economic revolutions, which promote sovereignty, dignity, peace, and fraternity among all people.

If the salvation of humanity is far away, it is because Washington insists on using its bullets against the world’s people.

We write and read these lines and this text in a moment that is

extremely tense for our planet. A virus is quarantining the global

economy, and capitalism – with its voracious habits and its need

to concentrate wealth – is showing its limits.

It is likely that the world that will emerge from the convulsions

of 2020 will not be the one that the one that we used to know.

Every day, we are reminded of the duty to continue our struggle

against imperialism, against capitalism, and against colonialism.

We must work together towards a world in which greater respect

for the people and for Mother Earth is possible. In order to do this,

it is essential for states to intervene so that the needs of the masses

and the oppressed are put first. We have the conviction that we are

the masses. And that the masses, over time, will win.

Evo Morales Ayma Buenos Aires Former President of Bolivia April 2020

I make no secret of my opinion that at the present time the

barbarism of Western Europe has reached an incredibly high

level, being only surpassed – far surpassed, it is true – by the

barbarism of the United States.

– Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, 1955

Books and documents that detail the tragedies afflicted upon the

people of the world surround me. There is a section of my library

that is on the United States government’s Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA) and its coups – from Iran in 1953 onward, every

few years, every few countries. The International Monetary Fund

(IMF) reports make up an entire bookshelf; these tell me about

the roadblocks placed before countries that try to find a way out

of their poverty and inequality. I have files and files of government

documents that had investigated old wars and new wars, bloodshed

that destabilized countries in the service of the powerful and the

rich. There are memoirs of diabolical leaders and advisors – the

complete works of Henry Kissinger – and there are the writings

and speeches of the people’s leaders. These words create a world.

They explain why there is so much suffering around us and why

that suffering leads not to struggle, but to resignation and hatred.

I reach above me and pull down a file on Guatemala. It is on

the CIA coup of 1954. Why did the US destroy that small country?

Because the landless movement and the Left fought to elect a democratic politician – Jacobo Árbenz – who decided to push through a moderate land reform agenda. Such a project threatened to undercut the land holding of the United Fruit Company, a US

conglomerate that strangled Guatemala. The CIA got to work. It

contacted retired Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, it paid off brigade

commanders, created sabotage events, and then seized Árbenz in

the presidential palace and sent him to exile. Castillo Armas then

put Guatemala through a reign of terror. ‘If it is necessary to turn

the country into a cemetery in order to pacify it,’ he said later, ‘I

will not hesitate to do so.’ The CIA gave him lists of Communists,

people who were eager to lift their country out of poverty. They

were arrested, many executed. The CIA offered Castillo Armas

its benediction to kill; A Study of Assassination, the CIA’s killing

manual, was handed over to his butchers. The light of hope went

out in this small and vibrant country.

What other day-lit secrets of the past are sitting in my files and

books? What do these stories tell us?

That when the people and their representatives tried to forge

a just road forward, they were thwarted by their dominant classes,

egged on by the Western forces. That what was left was a landscape

of desolation. Humiliation of the older colonial past was now

refracted into the modern era. At no time were the people of the

Third World allowed to live in the same time as their contemporaries

in the West – they were forced into an earlier time, a time with less

opportunity and with less social dignity. Tall leaders of the Third

World felt the cold steel of execution – Patrice Lumumba in the

Congo (1961), Mehdi Ben Barka of Morocco (1965), Che Guevara

in Bolivia (1967), Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso (1987), and so

many others, before, after, and in between. Entire countries – from

Vietnam to Venezuela – faced obliteration through asymmetrical

and hybrid wars.

This book is based on a vast amount of reading of US government documents, and documents from its allied governments and multilateral organizations, as well as the rich

secondary literature written by scholars around the world. It is a

book about the shadows; but it relies upon the literature of the

light.

‘Bring Down More US Aircraft’ Estados Unidos: el país donde

La libertad es una estatua.

United States: the country where Liberty is a statue.

– Nicanor Parra, Artefactos, 1972

What is the price of an assassin’s bullet? Some dollars here and there.

The cost of the bullet. The cost of a taxi ride, a hotel, an airplane,

the money paid to hire the assassin, his silence purchased through

a payment into a Swiss bank, the cost to him psychologically for

having taken the life of one, two, three, or four. But the biggest

price is not paid by the intelligence services. The biggest price is

paid by the people. For in these assassinations, these murders, this

violence of intimidation, it is the people who lose their leaders in

their localities. A peasant leader, a trade-union leader, a leader of

the poor. The assassinations become massacres, as people who are

in motion are cut down. Their confidence begins to falter. Those

who came from them, organized them, spoke from them, either

now dead or, if not dead, too scared to stand up, too isolated, too

rattled, their sense of strength, their sense of dignity, compromised

by this bullet or that. In Indonesia, the price of the bullet was in

the millions; in Guatemala, the tens of thousands. The death of

Lumumba damaged the social dynamic of the Congo, muzzling

its history. What did it cost to kill Chokri Belaïd (Tunisian, 1964–

2013) and Ruth First (South African, 1925–1982), what did it take to kill Amílcar Cabral (Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean,1924–1973) and Berta Cáceres (Honduran, 1971–2016)? What did it mean to suffocate history so as to preserve the order of the rich?

Each bullet fired struck down a Revolution and gave birth to our present barbarity. This is a book about bullets.

Many of these bullets are fired by people who have their own

parochial interests, their petty rivalries and their small-minded

gains. But more often than not, these have been Washington’s

bullets. These are bullets that have been shined by the bureaucrats

of the world order who wanted to contain the tidal wave that swept

from the October Revolution of 1917 and the many waves that

whipped around the world to form the anti-colonial movement.

The first wave crested in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

(USSR) and in Eastern Europe, and it was this wave that provoked

the Cold War and the East–West conflict; the other wave went

from Vietnam and China to Cuba, from Indonesia to Chile, and

this wave engendered the far more deadly North–South or West–

South conflict. It was clear to the United States, as the leader of

the West, that no muscular conflict would be possible along the

East–West axis, that once the USSR (1949) and China (1964)

tested their nuclear weapons no direct war would be possible.

The battlefield moved from along the Urals and the Caucasus into

Central and South America, into Africa, and into Asia – into, in

other words, the South. Here, in the South where raw materials are

in abundance, decolonization had become the main framework

by the 1940s. Washington’s bullets that pointed towards the USSR

remained unused, but its bullets were fired into the heart of the

South. It was in the battlefields of the South that Washington

pushed against Soviet influence and against the national liberation

projects, against hope and for profit. Liberty was not to be the

watchword of the new nations that broke away from formal

colonialism; liberty is the name of a statue in New York harbour.

Imperialism is powerful: it attempts to subordinate people to

maximize the theft of resources, labour, and wealth. Anyone who denies the absolute obscenity of imperialism needs to find another answer to the fact that the richest 22 men in the world have more wealth than all the women in Africa, or that the richest one per

cent have more than twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people.

You would have to have an answer for the reason why we continue

to suffer from hunger, illiteracy, sickness, and indignities of

various kinds. You could not simply say that there are no resources

to solve these problems, given that tax havens hold at least $32

trillion – more than the total value of gold that has been brought

to the surface. It is easy to bomb a country; harder yet to solve

the pressing problems of its peoples. Imperialism’s only solution

to these problems is to intimidate people and to create dissension

amongst people.

But liberty cannot be so easily contained. That is why, despite

the odds, people continue to aspire for alternatives, continue to

organize themselves, continue to attempt to win a new world – all

this despite the possibility of failure. If you do not risk failure, you

cannot taste the fruit of victory.

On 2 September 1945, H? Chí Minh appeared before a massive

crowd in Hanoi. He had never before been to the capital, but he was

known by everyone there. ‘Countrymen,’ he asked, ‘can you hear

me? Do you understand what I am saying?’ A few weeks before,

in Tân Trào, the National Congress of People’s Representatives

laid out the agenda for the new Vietnam. At that meeting, H? Chí

Minh said, ‘The aim of the National Liberation Committee and all

the delegates is to win independence for our country – whatever

the cost – so that our children would have enough to eat, would

have enough to wear, and could go to school. That’s the primary

goal of our revolution.’ The people in Hanoi, and across Vietnam,

knew exactly what H? Chí Minh was saying; they could hear him,

and they could understand him. His slogan was food, clothes, and

education.

To feed, clothe, and educate one’s population requires

resources. Vietnam’s revolution meant that it would no longer allow its own social wealth to drain away to France and to the West. The Vietnamese government, led by H? Chí Minh, wanted to use that wealth to address the centuries-old deprivations of the

Vietnamese peasantry. But this is precisely what imperialism could

not tolerate. Vietnamese labour was not for its own advancement;

it was to provide surplus value for Western capitalists, in particular

for the French bourgeoisie. Vietnam’s own development could not

be the priority of the Vietnamese; it was Vietnam’s priority to see

to the aggrandizement of France and the rest of the imperialist

states. That is why the French – in cahoots with the Vietnamese

monarchy and its underlings – went to war against the Vietnamese

people. This French war against Vietnam would run from 1946

to 1954, and then the mantle of war-making would be taken up

by the United States of America till its defeat in 1975. During the

worst of the US bombing of the northern part of Vietnam, H? Chí

Minh went on a tour of air defences. He was already in his late 70s.

His comrades asked after his health. ‘Bring down more US aircraft,’

he said, ‘and I’ll be in the best of health.’

Washington’s bullets are sleek and dangerous. They intimidate

and they create loyalties out of fear. Their antidote is hope, the

kind of hope that came to us in 1964 as the Colombian civil war

opened a new phase, and the poet Jotamario Arbeláez (translated

by Nicolás Suescún) sang of another future –

a day after the war

if there is a war

if after the war there is a day

I will hold you in my arms

a day after the war

if there is a war

if after the war there is a day

if after the war I have arms

and I will make love to you with love

a day after the war

if there is a war

if after the war there is a day

if after the war there is love

and if there is what it takes to make love.

A book like this relies upon a wide range of sources, but more than

that, it relies upon a lifetime of activity and of reading. Listing all

the books and articles would surely make this book double its

current size. I have been involved – in one way or another – in

the left movement for decades, and in these decades have been

active in campaigns against the criminal behaviour of imperialism.

And I have been reading about this behaviour in pamphlets and

newspapers for these past many decades. There is no greater clarity

for a writer than being involved in the very process that they wish

to write about; distance is useful, surely, but distance can also

create a false sense of dispassion.

My first indelible memory of political activity comes from

the US intervention in Grenada in 1983. Here was a small island

nation in the Caribbean, with not even a population of 100,000,

that had been experimenting with its own form of socialism

through the New Jewel Movement. The United States government,

rather quickly, developed a narrative that it fed to the corporate

press, of Cuban involvement in the New Jewel Movement and in

the government of its leader Maurice Bishop. This was likely true,

but the point was not whether it was true; the point was to tar the

New Jewel Movement with the brush of communism and Cuban as

well as Soviet involvement. It is precisely what the US government

had done to all revolutionary struggles in Central America and

the Caribbean in this period, allowing the bogey of communism to justify their support for the most wretched right-wing – often genocidal – forces in the region. My first essay for a newspaper was written on the US intervention into Grenada (it was published

in my school’s alternative newspaper, The Circle).

The first draft of history, the truism goes, is the media; like

all truisms, it is only partly correct. In the case of imperialism, it

is downright misleading. The corporate media in the West – and

the media elsewhere that mirrors it – is not capable of writing

the first draft of history because it is a part of the story. It takes

dictation from the imperialist institutions, such as the CIA, and

produces narratives that have varying degrees of truth to them,

but which are almost always stories that are framed by what suits

Western interests, rather than by the facts on the ground. To read

the media about Grenada after the 1979 revolution was to take

stenography from the US government. In 1979, for instance, the

New York Times ran a story called ‘Radical Grenada Symbolizes

Political Shift in Caribbean’ (20 August). The story was anchored

by two paragraphs of quotations from John A. Bushnell, Deputy

Assistant Secretary of State of Inter-American Affairs in the US

government. Bushnell said that while the US government does

‘not believe that Cuba is following some master plan for expanding

its influence in the Caribbean’, nonetheless ‘there also appears to

be a drawing together of young radicals and radical movements

in the Caribbean, encouraged by the recent events in Grenada and

perhaps also by Cuba’. Cuba, he said, is a ‘patron of revolutionaries’

and it comes to ‘the aid of radical regimes’. There was no detailed

account of the plans of the Bishop government; no voices from

that government, nothing really about the Grenadian people’s

desperation for a different kind of future.

To get the point of view of the New Jewel Movement, its own

newspapers were invaluable, as were the speeches of Maurice

Bishop; Bishop spoke openly about the challenges in this small

island and offered an expansive vision of what would be possible

if the people found themselves truly to be in charge (these are collected in Maurice Bishop Speaks, New York, 1983). For a socialistaccount of the revolution, the first draft of history must be the records of the government (1979–83) and the words left behind

by its architects. These offer the revolution in its own words. But

a revolution – like the counter-revolution – is capable of being

blinded by its own rhetoric, which is why its critics from the left

are often invaluable guides to the revolutionary process. In the

days before the internet, it was hard to follow these debates, easy

to be swept away by the calumnies of the corporate media. But

there were always solidarity platforms – such as the Ecumenical

Program for Interamerican Communication and Action (EPICA)

and TransAfrica – that produced their own dossiers and bulletins;

these would be filled with newspaper clippings and documents

of all kinds, a hodgepodge of essential information that would

circulate among leftists who were in solidarity with experiments

such as the New Jewel Movement and who were outraged by

imperialism’s antics. Such collections are key to the archive of a

book such as Washington Bullets.

In 1983, the US invaded Grenada and swept aside the New Jewel Movement.

It was not until 2012 that the National Security Archive – a

not-for-profit investigative project in the United States – was able

to attain 226 documents, largely from the US State Department,

about Grenada. These documents allow a meticulous researcher

to piece together the story of how the US government conducted

a hybrid war against the Maurice Bishop government and how

it created the conditions for its invasion. A close read of these

documents shows how obsessed the US government was with the

potential for Cuban and Soviet involvement in Grenada, and how

this motivated every negative policy decision of the administration

of Ronald Reagan against the New Jewel Movement. The real first

draft of history is this secret trove of documents, which come to

light decades after the event. This book is written with these sorts

of documents in hand, State Department and CIA materials that

158 Washington Bullets

are either available in the CIA’s own digital archive, or through the

National Security Archive, or else in the private papers of former

State Department and CIA officials as well as US presidents. It takes

a lot of effort to run down some of these papers, and even more

effort to learn to read them carefully. These documents cannot be

taken at face value because – as I have learned over the years in

talking to retired CIA and State Department officers – there is a

great deal of career-driven exaggeration. One has to sift through

the information with care and diligence.

Nothing is as valuable as hindsight, and often the best

hindsight comes in memoirs and in memories as well as in

academic work. Maurice Bishop was killed, and Milan Bish – the

key US ambassador – is now dead. But Wendy Grenade, who

teaches at the University of West Indies, Cave Hill (Barbados),

edited a book in 2015 called The Grenada Revolution: Reflections

and Lessons, which had an interview with Bernard Coard, who

was Bishop’s deputy and would have Bishop arrested (how Bishop

died remains a mystery); and two essays by participants in the

revolution – Brian Meeks and Patsy Lewis. A book such as edited

by Grenade presents an opportunity for participants to look back

and offer their own context for the revolution, and it allows other

contributors to assess the nature of the coup d’état against the New

Jewel Movement. The kind of book you have just read cannot

be written without reading the vast and important secondary

literature, often the best place to understand the contours of the

national liberation revolutions that provoke Washington’s bullets.

Nothing has been as useful to me in writing this book as the

conversations I have had with ex-CIA agents, people such as Chuck

Cogan, Rafael Quintero, and Tyler Drumheller. John Stockwell’s In

Search of Enemies (1978) is a book designed to clear the conscience

of a man who was disgusted by the work he had done. Stockwell

was in Grenada just before Bishop was killed; he went to Trinidad

and got the flu so was not present at the key moment when New

Jewel was destroyed. When the US invaded Grenada, Stockwell said that US President Ronald Reagan ‘likes controversy. It makes him look like what he thinks is a leader’. The US had exaggerated the Cuban presence in Grenada, Stockwell said, as a way to justify

the intervention. He knew this stuff from the inside out. Without

the input of people like Stockwell or Chuck Cogan, this sort of book

cannot be written. Before he died, Chuck met me several times

in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at a restaurant and would walk me

through his work in the Directorate of Operations in the key years

of 1979–84. I was then interested in the 1979 assassination of US

ambassador Adolph Dubs in Kabul; Chuck would say, ‘Don’t touch

that; it is too hot.’ But then he’d tell me another story, take me down

the road into another US-made disaster. This book is peppered

with insights I got from these men, who did nasty things, hated

talking about them, but were honest enough to say towards the

end of their lives that they had helped to make a mess of the world.