Techno-nationalism explained: What you need to know

https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/feature/Techno-nationalism-explained-What-you-need-to-know

Techno-nationalism changes the way providers do business and the way users interact with tech.

Techno-nationalism is a concept that ties technology and technological innovation to national identity, security, economic prosperity and social stability. It describes the way different countries approach technology governance and how the countries use technology to influence power in the global market. Also known as neo-mercantilism or multilocalism, techno-nationalism contrasts against techno-globalism.

In techno-nationalism, national governments may seek to protect their own interests by developing and promoting their own technologies and restricting the use of foreign technologies. Nations do this to maintain their own political, social and economic advantages. States may also view technologies developed by citizens of their country or promoted in their country as uniquely theirs.

What is causing techno-nationalism?

While the evolution of social media also plays a role in the proliferation of techno-nationalism, it ultimately breaks down into three parts:

- Governments pass policies, and regulations follow. Many global governments have a desire for digital sovereignty to keep their technology and data separate from other nations'.

- Information technology diverges due to a lack of interoperability and market protectionism.

- Business and commercial practices surrounding technology change to adapt to the new technology landscape.

With real-world trends, like the Fourth Industrial Revolution, advances in AI, big data and biomedical technology, contributing to governments' increased reliance on technology and as countries move further in their digital transformation, technology influences national economic, political and social standing more powerfully. These technological powers may enforce and empower different standards around censorship, data privacy, digital money, intellectual property and surveillance.

For example, an authoritarian government might rely on national champions, single companies given a dominant position by governmental policy, to run the economy.

At Davos 2019, Gen. John Allen, former president of the Brookings Institution, said: "As our digital entities, our techno-entities, gain economic capacity, increased markets and more capacity for investment, they begin to become almost statelike entities unto themselves -- given the population of the world they could influence at any given moment. We use the term 'digital citizen' because there are people in the world that feel more aligned moment to moment with a digital entity than the sovereign government 500 miles away that just preys on them."

How does techno-nationalism affect the economy?

Techno-nationalism is a trend in global technology ecosystems that sees economies becoming increasingly local, causing an increase in digital sovereignty regulations and a decoupling of technology stacks. Countries may begin to claim certain technologies as their own.

In theory, nations can use techno-nationalism to maintain an advantage over other nations, resulting in an increase in domestic production, job creation, increased investment and economic growth. It may also increase exports as other countries begin to rely on the nation for technology.

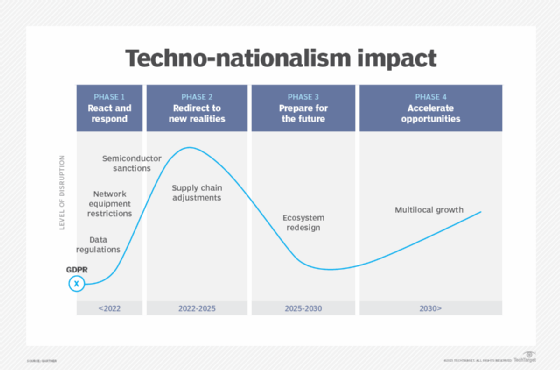

If multiple nations adopt techno-nationalism, there could be an increase in global competition, decrease in trade and rising international tensions if they find their national interests to conflict with one another. Economic disruption may increase as supply chains adjust to new techno-nationalist policies. After the disruption comes gradual business ecosystem redesign followed by growth of multiple local economies.

Gartner projected a basic pattern of economic disruption over the next decade as it relates to techno-nationalism.

Techno-nationalism and data sovereignty

Technological sovereignty, digital sovereignty and data sovereignty drive techno-nationalism through policy and regulation. Data sovereignty pertains to country-specific regulations that data residing in that country must abide by.

Foreign companies that do business in these countries are subject to data protection regulations. Business leaders need to understand where their data resides, as well as the laws of that country, to ensure proper compliance.

Data sovereignty affects both cloud providers that may have data centers in several countries and the customers who use their services. Businesses that use a cloud provider should not solely rely on their provider's governance, and these businesses should have their own policies to ensure data is both safe and compliant.

Countries may view data as a competitive advantage and enact policies to protect it. For example, a country may ban a foreign-made application because it views that application as a security threat. Countries may also aim to create entirely sovereign internets, separate from the larger global internet.

Examples of techno-nationalism

Techno-nationalism can be demonstrated in government policies and national strategies for technical innovation. A couple recent examples of techno-nationalist policies and strategies are the following:

- China's Made in China 2025 plan. Started in 2015, Made in China 2025 seeks to decrease China's dependency on foreign supply chains. The plan targets several industries, including AI, quantum computing, robotics, agricultural equipment and self-driving cars. The plan seeks to achieve 70% domestic content of core components and materials by 2025.

- America's CHIPS and Science Act of 2022. The CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) and Science Act of 2022 is an act designed to increase U.S. competitiveness, innovation and national security by investing in domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The act directs $280 billion in spending over the next 10 years with the majority of the funding going to scientific research and commercialization.

- Germany's Industrie 4.0 initiative. The national strategic initiative aims to drive digital manufacturing forward over a period of 10 to 15 years to ultimately improve Germany's competitive position in manufacturing.

- Russia's Sovereign Internet Law. This mandates the creation of an independent internet for Russia. Russia's sovereign internet is known as a splinternet. Splinternets are parallel fragments of the global internet that do not interact.

Divergent technology stacks are a feature of techno-nationalism. Applications are regionalized. Different countries have their own sets of companies, applications and application developers. Developers optimize their application for technology that is available or most convenient to use in their country.

Countries with policies that aim to optimize domestic consumption, empowering national champions, may have a more vertically integrated stack with less competition between companies at each level. One company provides an application that performs many functions. These apps have a larger scope than they have scale. One example of this is the Chinese application Meituan, which has more than 30 services with functions like ride-hailing, food delivery, home rental and payment. The application functions more like a portal to other services within the application. Apps like these are sometimes called super apps.

Contrast this against countries with policies that empower individual companies that address specific needs and encourage competition between companies. In this context, a composable stack is more common, with more competition and interchangeable providers at each level. Many companies provide applications that have one function, and those applications work together in the stack. For example, American applications, like Uber, Yelp, Fandango and Venmo, all address a specific function. These may all work on the same underlying infrastructure, but each application provides a different service. These app have more scale than scope -- they do one specific thing and target users with that specific need.