为什么中国的死敌印度不会成为美国的盟友

https://www.newsweek.com/why-india-chinas-bitter-foe-wont-become-us-ally-1792564#:~:text=

作者:Tom O'Connor,《外交政策》资深作家兼《国家安全与外交政策》副主编 2023 年 4 月 11 日

印度陆军司令警告说,印度已做好应对针对中国的“任何意外情况”的准备

在拥有世界上人口最多的两个亚洲邻国之间的紧张关系加剧之际,印度与美国和其他西方结盟国家的关系日益密切,同时对崛起的中国也越来越警惕。

但即使新德里采取了前所未有的措施来加强与华盛顿的关系,这个传统的不结盟国家似乎也不太可能与美国建立任何正式的防务联盟。

印度前驻华大使阿肖克·坎塔(Ashok Kantha)对《新闻周刊》表示:“事实上,我们确实将印度和美国视为天然盟友,但这并不是军事联盟意义上的盟友。”

这样的联盟将违背印度超过 75 年的后殖民历史,印度从英国赢得独立,并遭受与巴基斯坦的暴力分裂,引发了与邻国伊斯兰共和国和印度之间围绕有争议领土的几场战争中的第一场。 六十年前与中国的关系。 然而,即使在该国最严重的一些危机期间,印度也选择不在世界强国中选边站。

坎塔说:“我们经历了长达两个世纪的殖民统治,然后我们成为世界上人口最多的国家之一,这在民主、多元文化和开放社会方面也具有创新性。” “我们在冷战时期得出的结论是,印度不能成为当时美国和苏联这两个大国的阵营追随者,我们将与这两个国家合作。”

如今,尽管新德里将华盛顿视为更好的合作伙伴,但在中美摩擦不断加剧的情况下,印度称之为“战略自主”的政策仍在继续。

“我们不会保持同等距离,我们会在问题上采取立场,”他补充道。 “在某些问题上我们可能会与美国走得更近,但我们不会加入军事同盟。这一基本共识没有改变。”

为什么印度是美国的合作伙伴

在这张新闻周刊照片插图中,美国总统乔·拜登和印度总理纳伦德拉·莫迪于 2022 年 11 月 15 日在印度尼西亚努沙杜瓦举行的 G20 峰会上握手。

这样的立场从来不意味着中立。 在整个冷战期间,新德里与莫斯科建立了紧密的战略伙伴关系,这种关系至今仍然以外交互动的形式存在,并且俄罗斯在印度武装部队中拥有大量武器。

因此,尽管坎塔声称印度对俄罗斯去年二月在乌克兰发动战争的决定抱有“严重疑虑”,但他表示,“我们不会谴责俄罗斯,因为这种关系在历史上对我们很重要,甚至在今天也是如此。” 由于各种原因。”

然而,甚至在乌克兰冲突之前,坎塔就表示,新德里正在寻求军事伙伴关系多元化,这一趋势为美印关系提供了重大机遇,他在其中表示,“国防正在成为一个非常重要的领域” 区域。” 除了不断扩大的情报共享协议外,两国还进行了越来越多的联合演习,包括去年 11 月在印度与中国有争议的边界附近举行的 Yudh Abhyas 训练。

中印之间长达 2,100 英里的有争议边界,即实际控制线,是两国几十年来最严重紧张局势的根源,始于 2020 年发生的一系列致命冲突。 试图缓和局势,但手持棍棒和石块的部队之间的紧张遭遇和小冲突仍在继续。

在去年 12 月发生的最新一次公开承认的冲突之后,《美国新闻与世界报道》援引未透露姓名的消息来源称,美国在整个事件过程中向印度提供了实时情报支持。

坎塔在担任大使期间亲自参与了中印外交,他表示,北京近年来的行为“在印度和美国造成了深深的痛苦、焦虑和疑虑”。

坎塔说:“因此,虽然印度绝对不倾向于采取任何形式遏制中国,但我们认为像中国这样的国家是无法被遏制的,或者说我们对与中国经济脱钩也不感兴趣。” 我们更倾向于对中国采取某种去风险策略,我们倾向于建立威慑来防范中国的鲁莽行为,以避免重蹈2020年4月和5月在西部地区边境发生的事情。”

坎塔表示,印度面临的任务“主要是建立

发展我们自己的能力,但也需要对中国进行外部制衡,然后与美国和其他志同道合的国家合作将成为而且事实上已经是我们政策的重要组成部分。”

尽管他对在边界争端上没有取得重大进展的情况下中印关系的任何重大改善持怀疑态度,但他表示,避免更严重的冲突对于印度在其他方面实现其国家目标至关重要。

坎塔说:“这非常重要,因为我们的国防预算仍然相对有限,我们希望在可预见的未来专注于发展。” “因边界沿线的任何冲突或紧张局势长期升级而分散注意力绝对不符合我们的利益。”

印度,士兵,斯利那加,列城,高速公路,

1 月 6 日,在印控克什米尔斯利那加以东 67 英里的佐吉拉,印度陆军士兵在斯利那加-列城高速公路上的掩体外站岗。 这个战略关口连接克什米尔和位于的拉达克。

不列颠哥伦比亚大学客座教授斯瓦兰·辛格(Swaran Singh)拥有数十年在印度主要外交和军事机构授课的经验,他也认为,管理好这种关系对于实现两国的长期目标至关重要。

辛格对《新闻周刊》表示:“降级是唯一的出路,因为中国和印度都不能偏离其发展轨迹,也不能错过他们想象中的历史性复兴,成为世界事务的中心舞台。” “但随着两个快速增长的经济体和同等文明国家重新夺回自己在阳光下的地位,它们的竞争仍然不可避免。”

中国和印度之间的动态并不总是那么严峻。 虽然 1960 年代的边境战争、中国与巴基斯坦的密切关系以及印度在 1950 年代吞并西藏后主办西藏分离主义流亡政府的做法,助长了两个大国之间根深蒂固的怨恨,但这些努力始于 20 世纪 80 年代末, 2018 年和 2019 年,中国国家主席习近平和印度总理纳伦德拉·莫迪在各自国家举行了峰会。

然而,三年前,当新冠病毒 (COVID-19) 开始席卷全球时,两国发生了致命的边境口角,这标志着一个黑暗的转折。 印度外交部上周拒绝了中国重新命名印度声称拥有主权的领土内11个地点的决定,而中国外交部则批评印度内政部长阿米特·沙阿周一访问有争议的边境地区,这场争执继续成为头条新闻。

然而,由于边境紧张局势仍在发酵,辛格断言“双方都同意需要开始建立信任的新篇章,以适应他们作为快速发展的大国的新形象。”

与此同时,他表示,“双方都在继续进行大规模的前沿部署,同时也在致力于军事脱离接触,即使面对定期的核心指挥官级别和部际会议,这也是不完整和不平衡的。”

辛格说:“当他们学会处理双边和历史问题时,他们现在需要学习如何在新的大国形象中相互接触,特别是在地区和全球论坛上的互动。”

两国在某些关键领域至少取得了一些共同点,在日益多极化的国际秩序中获得了更多的相关性。 其中包括九个国家的上海合作组织集团和被称为金砖国家的非正式联盟,其中包括中国、印度、巴西、俄罗斯和南非。

阅读更多

这次选举可能会以台湾为代价给中国带来一个新的拉美朋友

两次台湾之行对最危险的中美问题的命运意味着什么

距战争边缘四年,陷入危机的巴基斯坦能否避免新的印度冲突?

其他一些国家已申请或表示有兴趣加入这两个组织,这两个组织承诺为了加强安全和经济协调而搁置双边争端。

尽管如此,中国在经济、军事和外交领域日益增长的影响力给新德里带来了风险和机遇。

辛格说:“虽然中国展现出前所未有的经济增长,巩固了其政治影响力和军事现代化,但中国的崛起使印度成为美国领导的自由世界秩序中现状大国的首选合作伙伴。” “这为印度打开了技术转让和国防合作的大门,使印度成为唯一展现出对抗中国能力的邻国。”

印度还加大了与美国、澳大利亚和日本一起参与另一个多边组织“四边安全对话”(俗称“四方”)的力度。 四方加强了成员之间的合作,中国经常指责四方试图组建一个以遏制中华人民共和国为基础的集团。

然而,与坎塔一样,辛格也指出,这些融入印度作为一个国家核心原则的联系是有限度的。

辛格说:“即使在独立和分治最脆弱的时刻,印度也选择了不结盟,这定义了其文明基因。” “今天,作为世界上人口最多的国家、第三大国防支出国、第五大经济体和拥有核武器的国家,这种情绪得到了加强,并反映在其多边结盟的公理中。”

他还认为,世界秩序的不稳定为中国和印度的角色发挥了更大的空间,这也有助于阻止双方有效地解决两国陷入困境的双边关系。

辛格说:“疫情和乌克兰战争肯定分散了中国和印度对双边问题的注意力,甚至使中印关系进一步复杂化。” “因此,虽然一个更加和平的世界可能会给他们提供纠正一些刺激的机会,但一定程度的边缘政策将继续定义中印关系。”

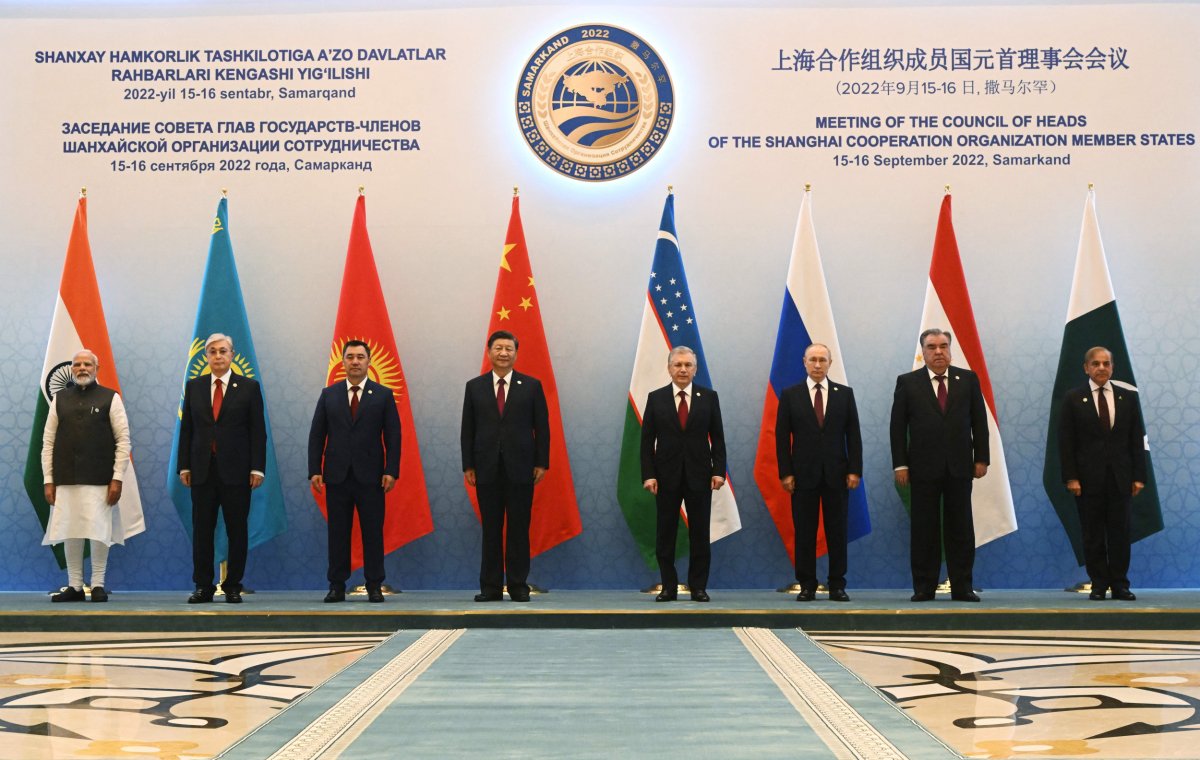

上海, 合作, 组织, 领导人, 峰会, 2022, 乌兹别克斯坦

(从左到右)印度总理莫迪、哈萨克斯坦总统托卡耶夫、吉尔吉斯斯坦总统贾帕罗夫、中国国家主席习近平、乌兹别克斯坦总统米尔济约耶夫、俄罗斯总统普京、塔吉克斯坦总统拉赫蒙和巴基斯坦总理沙赫巴兹。

尼赫鲁大学副教授、新德里战略与国防研究委员会创始人哈皮蒙·雅各布指出了中印关系复杂动态的另一个重要因素。

尽管美国去年超过中国成为印度最大的贸易伙伴,但中华人民共和国仍然是一个有影响力的经济参与者。 因此,雅各布告诉《新闻周刊》,“印度在公开谴责中国侵略方面缺乏共识,这主要是印度与中国经济关系的结果”。

但从根本上来说,他也认为持续不断的领土争端是导致中印关系下滑的主要原因。

雅各布说:“中印关系恶化的原因是中国在与印度边境的掠夺战略。” “中国也对印度与美国不断发展的伙伴关系感到不满,这(至少部分)首先是中国侵略的结果。”

他补充道:“如果中国恢复 2020 年夏季对峙之前的领土现状,不再对印度领土提出主权要求,双边紧张局势就有可能缓和。” “但我认为中国并不热衷于这样做。”

鉴于双方之间日益加深的不信任程度,曾在印度担任国家安全顾问的新德里观察家研究基金会研究员马诺吉·乔希(Manoj Joshi)也对《新闻周刊》表示,“两国和解的可能性很小”。 低的。”

乔希说:“两国一直非常谨慎地确保事情不会变得更糟,但似乎没有可以建立新的临时解决办法的共识。” “缓和局势是可以解决的,事实上,也正在解决中。但和解的可能性不大。怀疑不会轻易消失。”

他补充说:“局势仍将令人担忧,特别是因为双方继续在边界实际控制线两侧集结兵力。” “早期的进程是以寻求削弱此类力量的协议为基础的。”

但印度与美国日益接近也存在障碍。 尽管来自北京的威胁推动了新德里向华盛顿的转变,但印度和美国在许多其他地缘政治问题上存在分歧。

乔希说:“印度和中国之间的实力差距无疑是推动当前美印关系趋同的一个主要因素。” “但印度的立场主要是由其规模和利益驱动的。它认为来自巴基斯坦的重大安全威胁,而美国在不同时期一直是巴基斯坦的主要军事盟友。它认为伊朗是波斯半岛上相对温和的参与者。” 海湾和朋友,美国将德黑兰视为敌对参与者。”

乔希说:“这排除了与美国建立正式军事联盟的可能性,而这需要更加一致的观点。

Why India, China's Bitter Foe, Won't Become a U.S. Ally

https://www.newsweek.com/why-india-chinas-bitter-foe-wont-become-us-ally-1792564#:~:text=

By Tom O'Connor, Senior Writer, Foreign Policy & Deputy Editor, National Security and Foreign Policy Apr 11, 2023

India Ready For 'Any Contingency' Against China, Warns Head Of Army

Amid heightened tensions between neighboring Asian powers that are home to the world's two largest populations, India has grown closer to the United States and other Western-aligned nations, while becoming increasingly wary of a rising China.

But even as New Delhi takes unprecedented steps toward shoring up relations with the Washington, there appears to be little chance the traditionally non-aligned nation will establish any formal defense alliance with the U.S.

"In fact, we do refer to India and the USA as natural allies," former Indian ambassador to China Ashok Kantha told Newsweek, "but this is not in the sense of a military alliance."

Such an alliance would run contrary to more than 75 years of India's post-colonial history after winning its independence from the United Kingdom and suffering a violent partition with Pakistan, sparking the first of several wars over disputed territory with the neighboring Islamic Republic as well as one with China six decades ago. Even during some of the nation's most dire crises, however, India has opted to not choose sides among world powers.

"We had to suffer a period of colonial subjugation lasting two centuries, and then we emerged as one of the most populous countries in the world, which was also innovative in democracy, in multiculturalism and in an open society," Kantha said. "We came to the conclusion during the Cold War period that India cannot be a camp follower of either great power, at that time the USA and the Soviet Union, that we will work with both countries."

Today, this policy referred to by India as "strategic autonomy" continues amid growing frictions between the U.S. and China, even if New Delhi saw Washington as the better partner.

"We will not be equidistant, we will take positions on issues," he added. "On some issues we might be closer to the USA, but we will not join a military alliance. And this basic consensus has remained unchanged."

In this Newsweek photo illustration, U.S. President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi shake hands during the G20 Summit on November 15, 2022 in Nusa Dua, Indonesia.

Such a position has never implied neutrality. Throughout the Cold War, New Delhi forged a tight strategic partnership with Moscow, a relationship still very much alive today in the form of diplomatic interactions and the outsized presence of Russian weaponry comprising the arsenal of the Indian Armed Forces.

So, while Kantha asserted that India had "serious misgivings" regarding Russia's decision to launch a war in Ukraine in February of last year, he said "we abstain from condemning Russia because it's a relationship that has been historically important to us, and even today for a variety of reasons."

Even before the conflict in Ukraine, however, Kantha said that New Delhi was looking to diversify its military partnerships, a trend that has served as a major opportunity for U.S.-India relations, in which he said that "defense is emerging as a very major area." In addition to a broadening array of intelligence-sharing pacts, the two countries have pursued a growing number of joint exercises, including the Yudh Abhyas training that took place in November near India's disputed border with China.

The contested 2,100-mile boundary separating China and India, known as the Line of Actual Control, has been the source of the most serious tensions between the two powers in decades, beginning with a deadly series of clashes in 2020. The two sides have repeatedly attempted to de-escalate the situation, but tense encounters and skirmishes have continued among troops armed with clubs and stones.

After the latest publicly acknowledged clash that occurred in December, U.S. News & World Report cited unnamed sources claiming that the U.S. offered India real-time intelligence support throughout the incident.

Kantha, who was personally involved in navigating China-India diplomacy during his tenure as ambassador, said Beijing's actions in recent years "caused deep pain or anxieties and misgivings in India, as also in the USA."

"So while India is definitely not inclined to move towards any kind of containment of China, we believe that a country like China cannot be contained, or nor are we interested in the economic decoupling from China," Kantha said, "I think we are more inclined towards some kind of de-risking strategy vis-à-vis China, we are inclined to build deterrence to guard against China's reckless behavior to avoid a repetition of what happened along the borders in the western sector in April and May 2020."

The task at hand for India, according to Kantha, "will largely be building our own capabilities, but also requires an aspect of external balancing of China and then working together with USA and other likeminded countries will become, and is already in fact, an important component of our policy."

And while he was skeptical of any major improvement in China-India relations without serious progress made on the border dispute, he said avoiding a more serious conflict was crucial for India to achieve its national goals on other fronts.

"It's extremely important, because our defense budget remains relatively modest and we would like to focus on development for the foreseeable future," Kantha said. "Getting distracted by any conflict or protracted escalation of tensions along the borders is definitely not in our interest."

Indian army soldiers stand guard outside their bunker on the Srinagar-Leh highway on January 6 in Zojila, 67 miles east of Srinagar in Indian-administered Kashmir. The strategic pass connects Kashmir with Ladakh, which is located.

Swaran Singh, a visiting professor at the University of British Columbia with decades of experience lecturing at India's major diplomatic and military institutions, also argued that managing this relationship was essential for achieving the long-term objectives of both powers.

"De-escalation is the only way as both China and India cannot afford to derail their development trajectories and miss their imagined historic resurgence to the center stage of world affairs," Singh told Newsweek. "But as two rapidly growing economies and peer civilizational states reclaiming their place under the sun, their competition remains inevitable."

The dynamic between China and India was not always so grim. While their 1960s border war, China's close ties with Pakistan and India's hosting of the separatist government-in-exile of Tibet following the region's annexation by China in the 1950s fostered deep-rooted bitterness between the two powers, efforts began in the late 1980s and early 1990s to rehabilitate their relations and, as recently as 2018 and 2019 Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi held summits in their respective countries.

Their fatal border spat three years ago, just as COVID-19 began to grip the world, signaled a dark turn, however. The feud has continued to make headlines as the Indian Foreign Ministry rejected China's decision last week to rename 11 places within territory claimed by India and the Chinese Foreign Ministry criticized Indian Home Minister Amit Shah's visit to the contested frontier region on Monday.

And yet, with border tensions still simmering, Singh asserted that "both sides agree on the need to begin a new chapter of confidence building to suit their new avatar as rapidly developing major powers."

At the same time, he said "both also continue with heavy forward deployments while also working on military disengagement which has been, even in face of regular core commander level and inter-ministerial meetings, patchy and uneven."

"As they learnt to deal with their bilateral and historic problems," Singh said, "they now need to learn ropes of engaging each other in their new avatars as major powers and especially in their interface in regional and global fora."

The two countries have managed to share at least some common ground in certain key venues gaining more relevance in an increasingly multipolar international order. These include the nine-state Shanghai Cooperation Organization bloc and the informal coalition known as BRICS, in which China and India are joined by Brazil, Russia and South Africa.

READ MORE

This election may give China a new Latin America friend at Taiwan's expense

What two Taiwan trips mean for fate of most dangerous U.S.-China issue

Four years from brink of war, can Pakistan in crisis avoid new India clash?

A number of other countries have applied to or expressed interest in joining these two groups that promise to put bilateral quarrels aside in the interest of greater security and economic coordination.

Still, China's growing clout in the economic, military and diplomatic spheres have presented both risk and opportunity for New Delhi.

"While China has demonstrated an unprecedented economic growth that undergirds its political influence and military modernization, China's rise has made India the preferred partner for status quo powers in the U.S.-led liberal world order," Singh said. "This has opened doors for technology transfers and defense cooperation for India, making India the only neighbor that has showcased capacity to stand up to China."

India has also doubled down on its participation in another multilateral group, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, commonly known as the Quad, alongside the U.S., Australia and Japan. The quartet has intensified cooperation among members and it is regularly accused by China of representing an attempt to form a bloc built on containing the People's Republic.

But, like Kantha, Singh pointed out that there were limits to these ties built into India's core tenets as a nation.

"Even at its weakest moment of independence with partition, India chose nonalignment that defines its civilizational DNA," Singh said. "Today, as the world's largest population country, third-largest defense spender, fifth-largest economy and a state with nuclear weapons, this sentiment stands reinforced and reflected in its axiom of multialignment."

He also argued that the same instability in the world order that has made room for growing roles for both China and India has also helped to prevent the two sides from effectively catering to their ailing bilateral relations.

"Pandemic and the Ukraine war have surely distracted both China and India from attending to their bilateral problems, if not further complicated China-India equations," Singh said. "So, while a more peaceful world may avail them opportunities to redress some of their irritants, some amount of brinkmanship will continue to define China-India relations."

(L-R) Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Kazakhstan's President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Kyrgyzstan President Sadyr Japarov, Chinese President Xi Jinping, Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Russian President Vladimir Putin, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon and Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz.

Happymon Jacob, an associate professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and founder of the Council for Strategic and Defense Research in New Delhi, pointed to another important factor in the complex dynamic of China-India relations.

While the U.S. surpassed China as India's top trading partner last year, the People's Republic remains an influential economic player. As such, Jacob told Newsweek that there is "an absence of a consensus in India on openly calling out Chinese aggression, which is primarily a result of India's economic relationship with China."

Fundamentally, however, he too saw the ongoing dispute over territory as primarily driving the downturn in China-India relations.

"The reason behind the deterioration in Sino-Indian relationship is China's land grab strategy on the border with India," Jacob said. "China is also unhappy about India's growing partnership with the U.S., which (at least partly) is a result of China's aggression in the first place."

"If China were to reinstate the territorial status quo as it existed prior to the summer standoff of 2020 and stake no more claims to Indian territories, it is possible to deescalate bilateral tensions," he added. "But I don't think China is keen to do that."

Given the level of mistrust that has been fostered among the two sides, Manoj Joshi, a fellow at the New Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation who has served in national security advisory roles in India, also told Newsweek that "the chances of a rapprochement are low."

"The two countries have been very careful in ensuring that things don't go from bad to worse, but there seems to be no meeting ground on which a new modus vivendi can rest," Joshi said. "De-escalation can be worked out and is, in fact, being worked out. But rapprochement is unlikely. Suspicions will not go away easily."

"The situation will remain fraught, especially since both sides continue to build up their forces on either side of the Line of Actual Control that marks their border," he added. "The earlier process had rested on agreements that had sought to build down such forces."

But obstacles exist to India's growing proximity to the U.S. as well. While the perceived threat from Beijing has helped fuel New Delhi's shift toward Washington, there are a host of other geopolitical issues on which India and the U.S. are at odds.

"The power gap between India and China, is certainly a major factor driving the current convergence of U.S.-India ties," Joshi said. "But India's positions are mainly driven by its size and interests. It perceives a significant security threat from Pakistan, whereas the U.S. has been at various times a major military ally of Pakistan. And where it sees Iran as a relatively benign actor in the Persian Gulf and a friend, the U.S. has seen Tehran as a hostile player."

"This rules out the possibility of a formal military alliance with the U.S.," Joshi said, "something that would require a much closer identity of views."