现在全世界经济风风雨雨,都在看联储(美国央行)眼色,中国和发展中国家首当其冲,不过美国的富人也牵连在内。美国一旦加息,美元猛涨,除了对美国 经济是个打击,资金也从全球流回美国,发展中国家不但没钱了,堆成山一般的(美元)债务更是没法维持,难说不导致全球性的经济危机。这是为什么国际货币基金组织恳求联储别加息的原因。与此同时,即使全世界不 发生经济危机,光是美国经济所受的打击,美国股市必受重挫,那一来,美国有钱人的主要资产,股票为主,得大幅跳水,那是动了美国的根基,不能动。

所以上周联储按兵不动,我在美股翻身里说了,世界央行里,“美国是最婆婆妈妈的。 别看姚玲说话口齿伶俐,能言善辩,只字不提股市,其实一切行动,莫不以股市为中心,最无能。“

不这也好,股票接着涨,皆大欢喜。油也跟着上,只不过我以前说的“油价不可能上$40 ”要泡汤了。

有了背景,就得了解了解美联储和美联储常委。美联储由中央常委和各大军区组成。中央常委叫“Board of Governors”,头头是常委主席,就是姚玲了。各大军区是所谓“Federal Reserve Regional Banks”,共有纽约,波士顿,费城,亚特兰特,芝加哥,三番,克利夫兰,里士满,明尼苏达,堪萨斯,圣路易斯,达拉斯12区。一个军区的头头,司令员,是那儿的“President”。

【注】常委法定7人,但目前两党争斗,两个空出来的位子迟迟未能填上,故只有5人干活儿。

美联储是最婆婆妈妈的央行

美国就业很火,是美国经济领衔世界的主要体现,这也是联储的使命(之一)。按道理,该加息了。不过联储三番五次以“难见通胀”为借口不加。零利率和负利率对金融、经济扭矩很大,大家就盯着央妈,不愿意冒险。联储一边得说“美国经济全球领先”,但又得说“问题多多”,不说自打嘴巴。也是狡辩。过去几个月通胀见眉目了,联储又来“中国风险大(,不能让老大亏钱了)”,也难怪大家不信其“回归正常货币政策”的空头口号(The Fed's Credibility Dilemma)。

美联中央委员会(Federal Open Market Committee)由美联储常委(常任)加5位军区司令员(Regional Fed President)组成,共12人。纽约历来势大,纽约军区司令员是中央委员会常任委员,谁也赶不走。其它四个位子由12位司令员轮流,一年一任。排队明年进中央的,就是候补(alternate member)。每次中央全会,他们和其他司令员都能出席、发言,但无投票权。

国父哈密尔顿,如果不是杰佛逊顶着,差点儿没把纽约弄成首都。。大家熟悉独立宣言,起草人都是大智大慧的人,都是国父。不过贫民出生才华洋溢的哈密尔顿还是 瞧不起他们,自觉告他们一头,跟这些国父们都是死对头,结果被挤哒,郁郁不得志。不过哈密尔顿也不是省油的灯,有个才貌双全出生名门闺秀的老婆,还跟小姨 子谈感情,半公开地跟一有夫之妇通奸,最后别逼决斗,莫名其妙地丧了命。唉。

这不,大家现在又要把哈密尔顿从十元货币上摘下来了。

联储里的鹰派鸽派(投票资格是去年的,参见“候补”一项)

路透社实时鹰鸽图

联储自我科普:Introduction to the FOMC

现任:那个司令员进了c出了中央?

目前联储中央压倒性的是鸽派。这两天三番William, 亚特兰特Lockhart和芝加哥Evans出来说目前美国经济没问题,应当加息,对美元、股市浇了点冷水,大家是停顿揣摩以静待动。不过三人都不在中央,只有芝加哥市候补,成不了事。

上周中央表决按兵不动,让中国松了口气(见美股翻身)鹰派肯萨斯George是唯一反对的

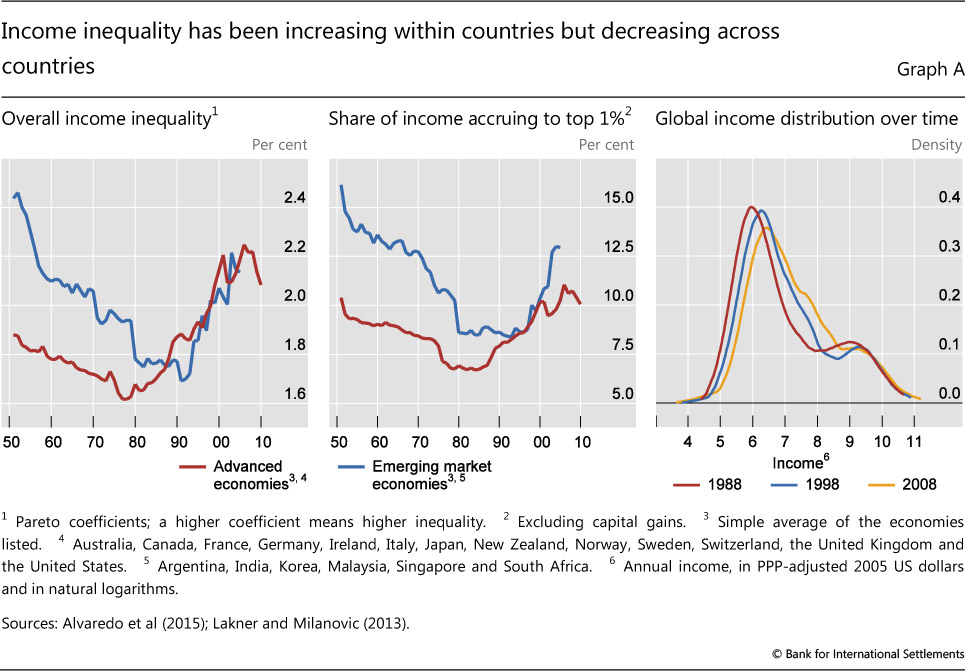

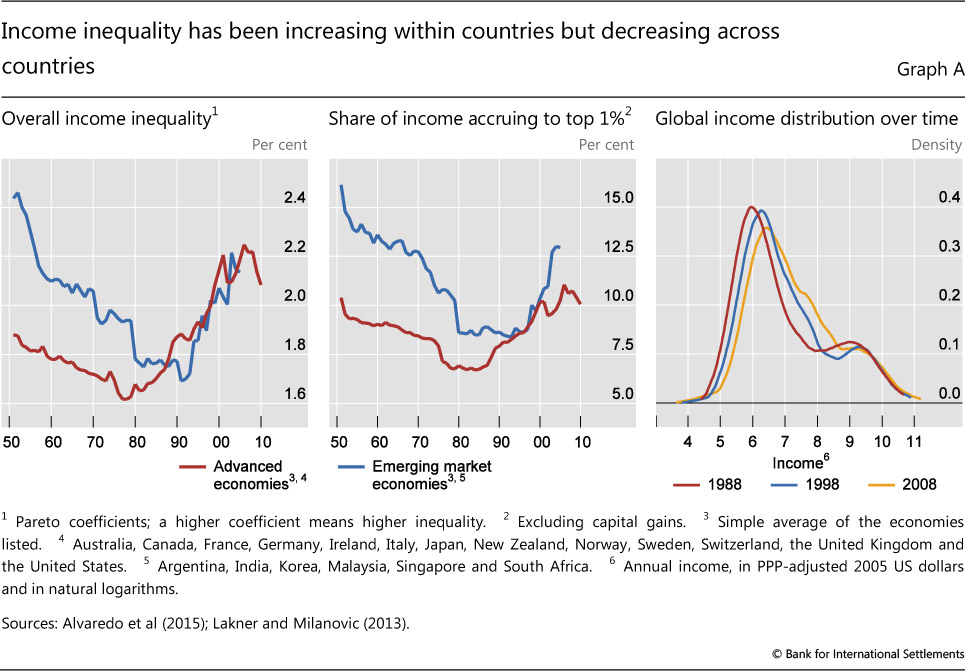

联储和不平等

大家一般认识

How Monetary Policy Impacts Income Inequality

问联储能做啥,姚玲说增加就业是咱联储能做的,唯一能做的,而且也做的不错。

6Yellen responded with a full-throated defense of how an “accommodative” monetary policy — or one that keeps interest rates low — actually reduces income inequality by maximizing job opportunities for the most vulnerable.

“To me the main thing that an accommodative monetary policy does is put people back to work,” Yellen said. “And since income inequality is surely exacerbated by having high unemployment and a weak job market — and that has the most profound negative effects on the most vulnerable individuals — to me, putting people back to work and seeing a strengthening of the labor market, that has a disproportionately favorable effect on vulnerable portions of our population. That is not something that increases income inequality.”'

联储辩护者说

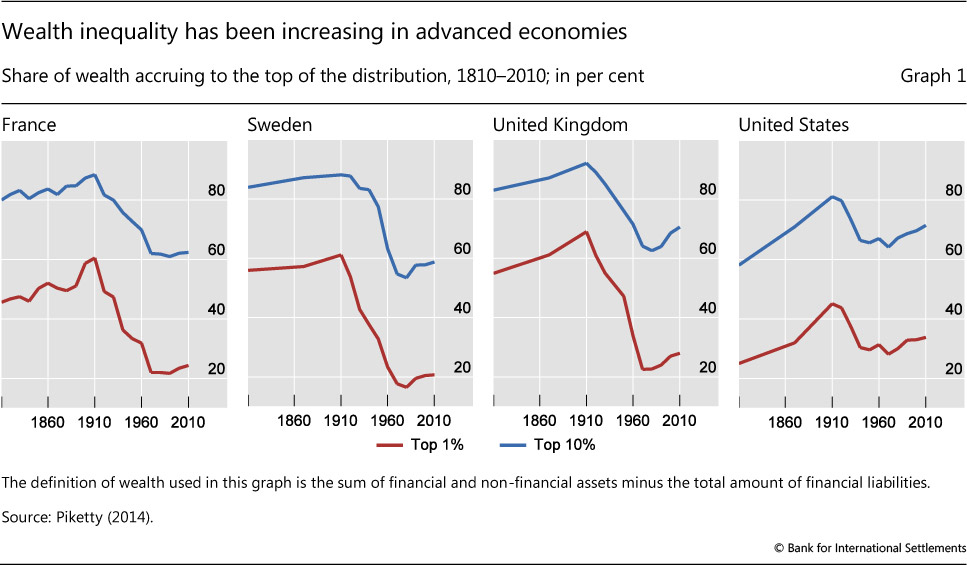

其实中产,而非顶层,获益最大,原因是得益最大的资产是房价,联储的政策对这个阶层的作用最大。也许极少数有钱人压在资产上财富倍增,但范围更广的上层(如5%)不少人都是积蓄了终身的老人,不敢将钱压在风险较大的资产上,也未必有路子(如私募),结果他们在固定利率产品上的投资基本全亏了,让联储吃了,成了受害者)我在“百里挑一又有何用?”唠叨过,0.01%的,得到的利益最大。联储难以辩护的,是这几个人吃的,大得不得了,参见我唠叨的百里挑一又有何用?。

现任美联储中央委员会:

2016 Committee Members

- Janet L. Yellen, Board of Governors, Chair

- William C. Dudley, New York, Vice Chairman

- Lael Brainard, Board of Governors

- James Bullard, St. Louis

- Stanley Fischer, Board of Governors

- Esther L. George, Kansas City

- Loretta J. Mester, Cleveland

- Jerome H. Powell, Board of Governors

- Eric Rosengren, Boston

- Daniel K. Tarullo, Board of Governors

Alternate Members

- Charles L. Evans, Chicago

- Patrick Harker, Philadelphia

- Robert S. Kaplan, Dallas

- Neel Kashkari, Minneapolis

- Michael Strine, First Vice President, New York

克利夫兰的Mester,也是个鹰派,没George那么“右”,但也常常出来说很多地方有通胀。不过上周她支持不加息

当代西方主流经济学家的观点是,西方的经济理论基本是对的,货币政策方面的使用,没有啥不妥的,风险经过美国2008金融大危机的考验,风险也可控,现在世界央行越救越大,没关系,没效果,那是还不够大,接着做,加码做,一定行。埃里安(穆罕默德·埃里安,Mohamed El-Erian)今年对此有个总结,说世上央行们认也好,不认也好,已是黔驴技穷了。

货币政策实施周期长,影响深远,一时半会儿改也改不了,其危害得一代人遭殃才能熬过。我对西方经济学在货币政策上的态度感觉是:过山车,总有一天大家一块死。

大起大落,没完没了

【注】

(中国)央行遵循西方经济理论的气氛也浓,周小川国内培训,副行长陈雨露郭庆平也属国内,但常常出头露面的潘功胜(国内博士,剑桥大学博士后学者及哈佛大学高级研究员)和易纲(伊利诺大学经济学博士)西方影响痕迹大,范一飞(中国人民大学经济学博士,美国哥伦比亚大学国际经济硕士)也有些瓜葛。

国际结算银行警告负利率的危害

What the central banker's central bank thinks about negative interest rates

(原文)Wealth inequality and monetary policy

对此,经济学家Diana Choyleva在《金融时报》有篇专栏,说这其实就是爱因斯坦所说的“疯了”。

《金融时报专栏》Central banks prove Einstein’s theory

Diana Choyleva

Fed, BoJ and ECB have not learned the lessons of financial crisis

©AFP

Albert Einstein is said to have defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. By failing to change their way of thinking since the global financial crisis, the world’s main central banks are proving Einstein right.

Many in the markets worry that central banks are running out of ammunition to boost global growth and generate inflation. They are not. The Bank of Japan’s adoption of negative interest rates, the European Central Bank’s extension of its quantitative easing (QE) programme and theFederal Reserve’s decision to slow the normalisation of US interest rates show that policymakers can still draw on plenty of firepower.

So it is not that central banks are not doing enough. It is that their policies are misguided and are hampering global rebalancing. In particular, investors should be worried that policymakers have failed to learn three main lessons from the subpar performance of the global economy since the 2008-09 crisis.

First, if an economy is drowning in debt, the solution is not to pile on even more debt. That is why the ECB’s offer, under the terms of its new targeted longer term refinancing operations, to pay eurozone banks to increase their lending is badly judged. The ECB is right to do QE, but at the same time it should use its new powers as the supervisor of eurozone banks to force a swifter write-off of bad debts. Almost 20 per cent of Italian bank loans are non-performing. Until now, the ECB has counted on QE to work by weakening the euro. Its strategy instead should be to use QE to buy time to cleanse bank balance sheets.

Second, no one wins from competitive devaluation when global consumer demand is weak because of excessive savings, as is the case today. The Bank of Japan has deployed the big battalions in the currency wars. Abenomics, the economic strategy of prime minister Shinzo Abe, was meant to combine monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and structural reform. Instead, in the past two years it has boiled down to a devaluation of the yen. On that narrow criterion, Abenomics might be judged a success — the yen has become so undervalued as a result of the BoJ’s loose monetary policythat traders are snapping it up.

But in fact the BoJ’s policy is as ill-thought-out as the ECB’s. Japan’s biggest economic imbalance is that too much income flows to companies, which sit on mountains of cash instead of investing it or returning it to shareholders. A cheaper yen compounds this problem. By boosting export earnings and making imports dearer, a weaker exchange rate transfers ever more income from households to the corporate sector. So the BoJ should welcome the recent recovery in the yen.

Unfortunately, the central bank has waited far too long to do the right thing. A financial crisis in Japan is now a matter of when, not if. As unlikely as it sounds in an economy fighting falling prices, the crisis will take the form of inflation. That will happen when Japanese banks run out of government bonds to sell to the BoJ, which will be forced to increase its purchases from insurers and other non-bank financial institutions. The result will be a rapid expansion in broad money, unmatched by growth in the real economy. That will unnerve domestic investors and spark a flight into US Treasuries and other overseas assets, sapping the yen. If the crunch comes in the next year or two the rest of the world will be too weak to withstand it.

Third, tepid growth since the crisis shows that a short, sharp adjustment and purging of past excesses is better in the long term than prolonged attempts to preserve the economic status quo. The Fed should have stuck to its plan to raise interest rates four times in 2016 instead of worrying that higher rates might hurt the rest of the world or asset markets might throw a tantrum. An upbeat message that higher borrowing costs were justified by positive domestic economic trends, notably a strong labour market, would have given US consumers the confidence to spend their windfall gains from cheaper oil.

In short, the ECB, the BoJ and the Fed have missed a golden opportunity this month to make much-needed course corrections. As a result, the euro area and Japan remain fragile while the US is not making the most of much-improved fundamentals, so the global economy is still perilously unbalanced. The world might muddle through for another year, but its leading central banks have failed to banish the risk of a calamitous 2017.

Diana Choyleva is chief economist at Lombard Street Research