纽约James Cohan画廊举办季云飞个展

2010-02-21 10:12 来源:99艺术网 编译:张明湖

纽约James Cohan画廊正在举办中国艺术家季云飞个展Mistaking Each Other For Ghosts,展出时间为2月19日至3月27日。展出包括艺术家最新的纸上作品及MOMA为艺术家出版的书籍《Migrants from the Three Gorges Dam》。

时间:2010年3月23日

地点:纽约 James Cohan

画廊电话:+1 212 714 9500

传真: +1 212 714 9510

| Yun-Fei Ji The Scholars Flee in Horror (detail), 2006 |

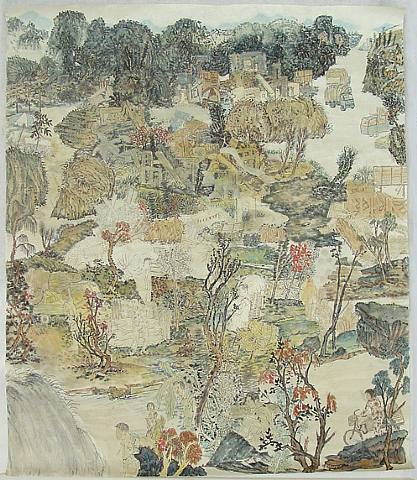

| Yun-Fei Ji Water That Floats the Boat Can Also Sink It, 2002-2005 |

Yun-Fei Ji was raised in China during the Cultural Revolution, a fact that fuels his exploration of Chinese contemporary history and directs his critical eye on issues of modernization. The title of the exhibition, “Water That Floats the Boat Can Also Sink It,” is a Chinese proverb that for Ji reflects the dark-side of development. The conflicting forces of water as provider and destroyer have been an essential theme for the artist. The Three Gorges Dam and the devastation it has caused throughout the Yangtze Valley, including the displacement of over 1.5 million people from their ancestral homes, have been subject matter for Ji’s allegorical paintings for a number of years. In this body of new works, the dam becomes the backdrop as Ji explores the cultural and psychological effects of the flooding on the rapidly changing fabric of Chinese life.

At first glance, the works appear to be traditional Chinese scroll paintings, but on a closer inspection, we are confronted with the less-serene depictions of homelessness and disaster. Yun-Fei Ji populates his richly textured landscapes with vignettes of village life in deep distress. We observe supernatural encounters with ghosts haunting the once densely populated valley, fleeing peasants scurrying through the demolished villages with their belongings on their back, and corrupt party officials flaunting their machismo while trying to find their role in the new China. Real life and fictional narrative collide, creating a dizzying array of historic and futuristic encounters.

Monumental in scale, Ji’s new paintings are his largest to date. The tallest vertical painting, Below the 143 Meter Watermark, is 118 inches high and has a stacked perspective that is densely filled with multiple layers of imagery. Water Rising is a long horizontal scroll diptych with the left panel measuring 204 inches and the right panel 114 inches. This diptych is hung on two perpendicular walls with the panels meeting in the corner of the gallery. The figures in the left panel of this cinematic drama are running toward the figures in the right panel as if they are due to collide with each other— they are fleeing with nowhere to go.

Yun-Fei Ji’s new body of work was completed while in residence at the American Academy in Rome on a Prix de Rome fellowship this past year. Ji first came to the United States on a Fulbright scholarship in 1985. Currently, he is living in London as an artist-in-residence at Parasol Unit, Foundation for Contemporary Art. In 2005, Ji had the honor of being artist-in-residence at Yale University where he was able to conduct extensive research with the help of scholars from a wide range of departments. Ji’s most recent solo museum exhibition in 2004, “The Empty City” originated at the Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis and went on to tour nationally at venues including the Rose Museum, Brandeis University, and the Peeler Art Center, DePauw University. In 2004, the exhibition “Yun-Fei Ji: The East Wind” was organized at the ICA, University of Pennsylvania. Ji’s work has been exhibited in solo and group shows throughout the United States and Europe including the Whitney Biennial 2002.

For further information, please contact Jane Cohan at jane@jamescohan.com or telephone 212-714-9500.

The show will open November 16 and run though December 22. For more images of new works please see www.jamescohan.com.

季云飞,1963年生于北京,年仅15岁的他考入中央美院油画系,19岁大学毕业。1986年,季云飞移居美国。纽约著名的现当代美术馆MoMA收藏了他的两幅作品,直到2002年,季云飞才开始为美国艺术界所知。当年的惠特尼双年展是他在美国第一次重要的公开亮相。此后,季云飞参加的展览越来越多。2005年是季云飞的转变之年。他获得了美国罗马学院颁发的罗马奖。罗马学院是西方各国设立在罗马的艺术学院。 季云飞的画黄黄的、旧旧的,连他自己都说是“烂纸旧画”。也有人评价说:“他的画古怪,有梦幻色彩,并非表面的水墨画,而是融合了很多西方超现实的概念。”

Blind Stream, 2008

Yun-Fei Ji, detail from “Water Rising,” 2006, Mineral pigments and ink on mulberry paper.

季云飞出生和成长于文化大革命时期,两岁时就与父母分离,在杭州附近的集体农场生活,没有电视和广播,他的童年就在祖母讲的鬼怪故事和童话中度过。季云飞在中央美术学院学习了传统中国绘画技巧,随后又于1986年前往美国继续深造。按照季云飞自己的话来说,他是运用山水画来探索从过去的集体主义到现在消费主义的中国历史的乌托邦梦想。

在新作品中,季云飞延续了借用历史与当代连接的方式,重访民间文学的宝库,将蒲松龄笔下的鬼怪精灵重现于当代社会背景之中。

季云飞于2005年获得美国罗马学院颁发的罗马奖,成为获得该奖项的第一位中国人,并于当年签约了James Cohan画廊,他的作品也已被MOMA收藏。

门外的陌生人季云飞

季云飞是一个典型的慢人,说话慢、画画慢、成名慢。他是少年神童,但比师兄徐冰成名晚了10 多年。在美国定居21 年,他的慢积淀出不一样的东西来,2005 年,他成为美国罗马学院百年历史上第一个获得罗马奖的中国人。这次,他的两幅艺术单品回国参展。他的回国展览比早已从美国杀回来的徐冰整整晚了7 年。

文/ 丁晓蕾 摄影/ 小武

“上海艺术博览会国际当代艺术展”现场,纽约詹姆士?科恩画廊(JamesCohan)的展品在无声地表明自己的身价。画廊门口站着Video 艺术之父白南准的作品。这个著名的装置作品《电视花园》像一名脾气古怪的迎宾员,身上装着十来台电视机注视着来来往往的过客。而抽象派英格雷德?卡兰、 视像装置艺术先驱比尔?维尔拉、德国大师演维姆?文德斯的摄影作品也成为镇店之宝。

画廊左侧全部让给了一个陌生的中国人——季云飞。

两幅出自季云飞之手的水墨画,跟光怪陆离的装置和油画相比,保守古旧、格格不入。

跑过去向画廊市场总监邵希亚(Arthur Solway)打听作者是谁的多半是中国人,而老外则去问价钱。在另一家纽约CRG 画廊展出的华人艺术家张欧告诉记者:“现在,Yun-Fei Ji 这个名字在美国叫得很响。”

“Yun-Fei Ji”是季云飞的英文名字。

海外出名,中国陌生

拿国际著名策展人巫鸿的话来说,季云飞就是一介书生。在艺术展热火朝天进行时,他还在纽约的画室做自己的作品。

“我是个慢性子。”电话那头的季云飞一字一句地说。

1986 年,季云飞移居美国。1987 年,谷文达、蔡国强移居美国和日本,1991年,徐冰移居美国。在展览上,同期出国的徐冰、谷文达的作品身价已经高他许多倍,季云飞的长卷《Water Rising》售价为13.5 万美元。

季云飞坦白地说:“看别人出名自己也羡慕,也想好好办个大展,但没办法,只能把自己的事儿做好,慢慢来吧。”纽约著名的现当代美术馆MoMA收藏了他的两幅作品,此前,被MoMA收藏作品的中国艺术家有蔡国强、徐冰、方力均等四位。最近,MoMA 的人找到季云飞,要为他出一本画册。

直到2002 年,季云飞才开始为美国艺术界所知。当年的惠特尼双年展是他在美国第一次重要的公开亮相。此后,季云飞参加的展览越来越多。

2005 年是季云飞的转变之年。他获得了美国罗马学院颁发的罗马奖。罗马学院是西方各国设立在罗马的艺术学院。著名画家德加、安格尔等都曾在罗马学院学习过。美国罗马学院成立于1904 年,已有百年历史,季云飞是迄今为止第一个获得罗马奖的中国人。

这一年,季云飞转签纽约一流的詹姆士?科恩画廊。 科恩画廊成立于1999 年,主要经营已成名的和正崭露头角的国际当代艺术家的作品。当年的画廊开幕展就出手不凡,展出了吉尔伯特和乔治的早期艺术作品。季云飞是画廊代理的唯一的华人艺术家。

而在中国,季云飞几乎不为人知。出现在“上海当代”现场的这两幅画,是他第一次在中国展出。当记者换成中文名字搜索他时,连一份完整的画家简历也搜不到。

新一代老怪

一次,一位朋友特地跑去展览现场看季云飞的作品,回来后告诉他,根本没看到他的画。“我的画很容易被忽略,”季云飞笑着说, “我不喜欢画那种给人视觉冲击力很强的画,我希望让人慢慢读出画中的故事。”

季云飞的画黄黄的、旧旧的,连他自己都说是“烂纸旧画”。在2006 年的作品《The Dead Can Still Dance》里,山上的树林里隐藏着兽面人身的妖怪,透明的鬼魂和骷髅若隐若现,仿佛山林中在开一场盛大的死亡宴会。

在表现三峡移民的作品《Last DaysBefore The Flood》里, 季云飞使用典型中国山水画的布局,画面都是山林和河水,但现代建筑物间出其中,大都是中国乡村的二层小楼,只是屋里街道都空无一人;画面的左下角有三五个人在赶路。显然,他们是最后一批离开村子的人。同样毕业于中央美院,留学美国,季云飞与师兄 “海外四大天王”之一的徐冰走的是完全相反的道路。徐冰比季云飞大12 岁,学水墨画,出国之后完全转向了观念艺术,他的成名作《天书》都是大尺寸,有扩张性、政治性的。而季云飞出国后反而更加珍视起中国的传统,不玩观念,不做装置,索性开始一笔一画地画起水墨画来。

1991 年,徐冰到美第一年就在威斯康星州文维姆美术馆举办了个人展览,而季云飞直到2001 年才在纽约布鲁克林pierogi 画廊举办个展。

季云飞坚持着自己的兴趣,选择了一条通向成名的最慢的道路。就算是一直关注美国华人艺术家变迁、对美国艺术圈很熟悉的巫鸿,也是通过惠特尼双年展才知道季云飞。“有人说他在美国出名靠画国画,但想想看,画国画的人实在太多了,要出名实在太难了。”

巫鸿说: “他的画古怪,有梦幻色彩,并非表面的水墨画,而是融合了很多西方超现实的概念,比如西班牙戈雅的传统;还有,我在他身上看到了过去扬州八怪的影子。他很像石涛和罗聘。”同是经历过“文革”时期的一代人,季云飞的感受不会比徐冰、谷文达少。季云飞在作品中创造了一套属于他自己的绘画语言,鬼怪、灵魂都是他的语言符号,他用比喻的方式把传统和前卫的东西结合起来。同时,他在作品中展现的都是中国历史中的重要事件,除了三峡移民,还涉及鸦片战争、义和团运动、河流环保等近现代中国的历史事件。2002 年,他创作的三峡移民系列,成为他被纽约艺术圈认可的代表作品。季云飞画画非常慢。他喜欢在画上表现层次感,加入很多隐藏的元素,画一幅画要琢磨很久,一幅画动不动就要花上两三个月的时间。近年来逐渐有了影响力之后,买画的人越来越多,但他还是保持着自己画画的速度。宣纸薄,经不起折腾,有时画到最后一下子破了,就一切再从头开始。低产让他错过了很多展览机会,“画廊的人也挺着急的,不过也没办法。”季云飞说。

隐居纽约的中国民间艺人

季云飞,北京人,生于1963 年,妈妈是知青,父亲是随军医生,他从小在杭州的军区大院长大。

季云飞绘画中的很多元素都可以从他的童年找到源头。有一段时间他被送去跟乡下的外婆同住,听外婆讲鬼故事就成了每天最好的娱乐。在季云飞的作品中,人物总是面无表情,若隐若现,仿佛鬼魂一般,源于童年时对鬼故事的迷恋。长大后,他读《聊斋志异》,很欣赏其中充满人性的鬼的形象,他说,“通过死去的魂灵讨论生者,这是个好办法。”在“文革”时期军区大院长大的季云飞保持了少年的敏感和反叛。他早早地显露了绘画天赋。10 岁时,母亲送他到一个专门画军事训练示意图的军官那里学画。“文革”结束高考恢复,年仅15 岁的他考入中央美院油画系,19岁大学毕业,被周围的人视为“神童”。“我在一个什么都讲究快速进步的环境中长大,”季云飞说,“我的父辈们热情非常高涨,希望在很短的时间内赶超英美,但之后‘文革’等事件的发生让他们非常失落。”

当时的中央美院还在苏联画派的笼罩之下,而老师们反复画领袖像的行为让季云飞觉得无趣,也许是因为少年的叛逆,在大三那年,季云飞的兴趣更多地转向了中国传统绘画和书法篆刻,尤其喜欢以陈老莲为首的明末“四大怪杰”。快毕业时,季云飞跟着老师一起去敦煌写生。莫高窟讲述佛经故事的壁画和佛像深深地打动他,回北京之后,他也采用类似的叙述方式、。这一次旅行,改变了他后来的创作道路。

1986 年,在北京工艺美校教书的季云飞获得了阿卡萨斯大学的富布莱特奖学金资助,赴美留学。硕士毕业之后,季云飞到了纽约,在一些朋友的帮助下安顿下来,他一直获得各种学院和基金会的支持,生活过得虽不富裕,但却支撑得下去。

没有生存的压力,让季云飞更加专心地发展自己的绘画。多年的纽约生活也影响了季云飞的创作风格。季云飞承认比利时静物名家让?勃吕盖尔以至美国地下 大师罗伯特?克鲁博对自己的影响。

另外,季云飞还受到文学作品的启发,从曹雪芹、白居易,到波兰裔英国作家约瑟夫?康拉德等,他还喜欢维姆?文德斯和科恩兄弟的电影。大事件下的小人物、他们的生存状态,成为季云飞的兴趣所在。影响季云飞最深的,还是中国传统的民间文化,不论是绘画还是传说、故事、音乐,“我甚至以为自己就是个民间艺人。”季云飞说。

现在,季云飞住在纽约布鲁克林一个新兴的艺术家聚集地。 季云飞喜欢自己在纽约的生存状态,周围都是来自世界各地的艺术家,他每时每刻都能感受到不同文化的碰撞。他甚至在爵士乐中攫取灵感,在去三峡考察期间,他带着画笔画纸,走到哪画到哪,“这是即兴创作,就像爵士乐里的即兴部分。”季云飞希望能在不久之后回国办个展,他说:“等有了合适的机会,慢慢来吧。”

http://www.brooklynrail.org/2006/12/art/yun-fei

Yun-Fei Ji with John Yau

by John Yau and Yun-Fei Ji

Photo of the artist by Phong Bui.

Photo of the artist by Phong Bui.During his brief visit to New York for his first one-person exhibit at James Cohan Gallery, “Water that Floats the Boat Can Also Sink It: New Work by Yun- Fei Ji”, which will be on view till December 22, the artist came to visit Rail’s art editor John Yau to talk about his new body of work.

John Yau (Rail): Did you make all the work in your show at James Cohan Gallery during your stay in England?

Yun-Fei Ji: Most of the work actually got started while I was in Rome on my Prix de Rome fellowship last year. Then with the last piece, Water Rising, which is a long horizontal piece that has two panels that meet in the corner, it was started in Rome and got finished in London. In fact, the first two attempts didn’t quite work out, but I managed to pull through in the last one. The reason for this was simply in the early conception of Water Rising, the group of displaced people who are carrying their belongings was initially on the left of the bottom area. So I moved them to the right in the first panel and likewise in the second, from right to left, and they eventually meet and disappear into the wall.

Rail: Because it is a corner piece that almost mirrors itself in terms of how the images are read.

Ji: Right. In the early version I painted just people as silhouettes against an empty background, and I was hoping, by describing what they carry with them, it would say something about each of the characters. So I did a lot of sketches, which were based on my archives of digital photos that I took of the people in their villages from my trips to China over the years. In the second version I felt I was being too heavy-handed, but in the last I was finally able to make it in a way that sometimes the people would disappear into the landscape, while other times you see the littered landscape of the area where they were taking and putting things in their baskets; what they couldn’t take with them they had to leave there, by the side of the road, and the scavengers would come and collect the abandoned things, in order to reuse or sell them. The torn-down houses enhance the whole scene, which adds to the feeling of desperation.

Rail: You are talking about a massive relocation that involves a few million people.

Ji: Anywhere from 1.5 to 1.9 million people from an area with about a 500-kilometer radius, there are about a thousand villages and about three fairly large and old cities. You know the villages and cities on the Yangtze River, where there is a long history: it used to go through Sichuan province and the only route to get there is by taking a boat upstream for hundreds of miles; it’s a very mountainous area. The Yangtze River is one of the longest rivers in the world. It starts from the Tibetan plateau, melting ice coming down to Sichuan province and Chongqing, one of the three largest cities in China, and then comes downstream into the Three Gorges area bordering the Sichuan and Hubei provinces in the west, the central part of China, where it has a thousand twists and turns and the riverbed becomes very narrow. That was why, a hundred years ago, people were already thinking of building a dam there. Mao in fact was thinking of having hydroelectric power developed in that area and the government is still working on it right now.

Rail: And that’s going to be finished in 2009?

Ji: 2009, yeah. But the water now has risen to 175 meters, and the first time I visited this area they were in the process of dismantling the cities.

Rail: when did you first go there?

Ji: 2001 or 2002

Rail: And when did the project itself start?

Ji: The physical construction began in 1990.

Rail: Did they build cities for the people to move to?

Yun-Fei Ji, “The Scholars Flee in Horror” (2006). Courtesy of artist and gallery.

Yun-Fei Ji, “The Scholars Flee in Horror” (2006). Courtesy of artist and gallery.Ji: Yes, there are immigrant cities that are higher up in the mountains. So, if you have a city resident card and you move to “the cities,” you get compensated according to the size of the apartment or house you previously owned. They would give you a certain amount of money, which allows you to relocate and buy an apartment in the immigrant cities. Or if you are from the village, you will be relocated all across China, which could be a thousand miles away.

Rail: So the villagers had to suffer more than the townspeople. This whole project would break up the villagers’ traditional family system.

Ji: Yes, for generations. You know, villagers had to dig up their ancestors’ graves and take their bones with them; it’s quite sad.

Rail: Ghosts in China are very different than ghosts in America or in the West. You said that they coexist with the living in a very real way.

Ji: Yeah, when I was growing up in a village with my grandmother, because there was no television, no radio, and no films, she would tell me all kinds of ghost stories and legends that are basically parts of the oral tradition, storytelling, which is still very much alive among many people in China, particularly if they live in a village. For example, the legend of Lui Jai Ji Yi has a different folk spirit, but given so much humanity, she is free to speak her mind. That’s why ghosts are the most popular vehicles for substituting what people can express in such a tightly controlled society where you, the living, can’t say it.

Rail: And in a way you are implying that the three Gorges Dam Project is disturbing all the ghosts or bodies that have inhabited that region.

Ji: But it’s also the idea of modernity, which kind of wipes everything out. So ghosts and other local legends are slowly disappearing as a result.

Rail: That is a big issue with China; everything has to be changed in such a hurry so they can catch up with modernity. I mean the Three Gorges wasn’t a pilgrimage site, but primarily for enlightenment.

Ji: Every child in China who reads a story about coming down the Yangtze River through the Three Gorges, knows about all the legends, and can recite all those poems; but this is the area they are going to change. Archeologically, it was quickly organized by the government to dig up and keep as many things as possible before the flood. They even built a museum for it, but there are so many remnants, it was just impossible to recover everything in such a short period of time. It’s a very unfortunate situation.

Rail: Increasingly, that’s what we hear about, how China doesn’t know what to do with the past.

Ji: As a child growing up in China, you would learn the modern history of China. It began with the opium wars, which initiated our long struggle against the West and colonialism; it was very brutal, humiliating, and eventually led to unfair treaties where Hong Kong was leased to England for a hundred years.

Rail: So it’s a history of overcoming humiliation?

Ji: Yeah. Because you are living under the imposed rule of western powers, you kind of have to internalize all of that in order to catch up, and be modern. Otherwise you’ll be cut into pieces. Most people seem to think that our long and invested tradition in Taoist or Confucius ideas led to this horrible state of affairs. That’s why, when Mao came to power, he said we needed to have modernization, we needed to have the state, and that all these countries in the West were trying to threaten us. The people rallied behind him until the Cultural Revolution disillusioned them. Everyone realized that we needed a change in everything, including the government.

Rail: Do you think that living through the Cultural Revolution as a child had a profound effect on you and your family?

Ji: Undoubtedly yes, though my family was luckier than others. At the same time maybe some of this message, Mao’s idea of rebellion, or of disregarding authority, helped get people to think for themselves.

Rail: So the Cultural Revolution also had a reverse effect, and got people to distrust the government. I know that many people, at least two generations, couldn’t and didn’t go to school for years. Is that what happened to you?

Ji: We were running wild for about eight or nine years. It was terrible.

Rail: Ha Jin, the writer, told me a story about how, when he was stationed in Mongolia during the Cultural Revolution, they would get armed with sticks and cross the border and fight Russian soldiers for fun. All the soldiers in his group were teenagers around fifteen or sixteen, I believe. And this was the way they passed their time.

Ji: By the time Mao died in 1976 and Deng Xiaoping came to power, we were exhausted from the political struggle and endless meetings. People just got fed up with the subsequent corruptions. It was a very disturbing time.

Rail: Your family was taken apart right?

Ji: Yeah, and my mother was kind of in trouble for a while.

Rail: But at this same time, you went to the Academy where you were trained under the program of Socialist Realism via the Soviet Union. It must have been strange to see artists who had been rehabilitated, allowed to paint for the first time probably in years, who are your teachers, who are afraid to paint anything other than what they are supposed to paint.

Ji: They were products of the 1930s, they had a lot of progressive ideas, they developed their own language, but when the Cultural Revolution started they were all sent away to the factories and the farms so they were deprived of their own work as artists. So when they came back they were in their fifties and they were our teachers in school. Some of them were able to make new work, because when Deng Xiaoping came to power, he hadn’t yet drawn a line and said, “There is the boundary.”

Rail: So everything was possible for a while, but when Xiaoping drew the boundaries of what you are suppose to do in 1982, ’83, with reference to the anti-spiritual pollution, what happened then?

Ji: That was sort of a wake up call to all of us. Once again, we became disillusioned just like before.

Rail: But there was a brief moment in the late 70s where Chinese painting seemed to be starting to develop into a new direction. And then in the early 80s it all got shut down again. Were you still in school then?

Ji: I actually graduated and then quickly went to teach in Beijing.

Rail: Is that where you learn about classical Chinese painting?

Ji: Yeah, I had some colleagues who were doing calligraphy, and also because of my early visits to old Buddhist sites while I was still in school. I went to Tibet, and we did a lot of copying of those beautiful Tangka paintings, which depict hundreds of years of Buddhist art from the period of mid-16th century. So it was a combination of both that finally led me to study and pay more attention to classical Chinese painting.

Rail: So you went on a trip to Tibet, what was that like and how old were you?

Ji: I was eighteen. I went with a friend and two of our teachers. One of them was in Tibet for twenty years. He was sent there to be rehabilitated, so while we were there, he had a lot of Tibetan artisans visit him and we were drinking together a lot. They took us to visit Jokang, the third largest temple in Tibet.

Rail: So even, say, in China, during this moment of the melting of the ice, there is this other culture within the very structured society of artists and that culture is a little bit outside the mainstream, I mean there is obvious communication because this teacher has been rehabilitated but he has Tibetan students, so then something else happens, information gets passed around below the surface.

Ji: Yeah that’s true. My teacher did a lot of beautiful charcoal drawings of Tibetans, I remember when I was a kid I would copy them. Otherwise most other things were very stylized propaganda work in which you had to follow the proper hierarchy. So I was happy to study with him. Also, the drawings are part of what they did. It was the result of the time they spent with Tibetan farmers. The drawings were more fresh, and more interesting than the paintings, which they’d spent months working on in the studio, because they had to represent history in a certain way.

Rail: Because they had to idealize everything.

Ji: The first and most important story is of the Communist Party member, the leader had to be in the center with his supporting casts surrounding him, then the farmer and so on. Everyone was assigned a place within the painting, and it all depended on your status within or outside the Communist Party.

Rail: A hierarchy where the intellectual is at the bottom (laughs). And you are aware of all those codes and symbolic structures in Chinese classical painting which also exist in socialist-realism, and you were saying earlier that when you were in Rome you were interested in the hierarchy of Christian iconography for the same reason: Christ in the center and all other beings surrounding him. One of the ways you seem to look at art is to see that there’s a symbolic structure that is used as a scaffold to hold the information. For example in the big vertical piece, Below the 143 Meter Watermark, you pointed out that people are going only so high up on the mountain, as if the mountain is really the symbol of the government.

Ji: Of course, the farmers are the people with no voice at all. Even though in the Chinese system, there is such thing as petition, where, if they were abused, they can go to high government officials to petition. But that process can take years for the officials even to look at the case. And most of them are too poor to go through that agony. Some have and ended up losing everything. Thinking about their struggle with the government’s hierarchy and corruption, I went back to study the great paintings of the Sung period, where the institution of landscape painting was actually established. And according to their values, the main mountain represented the central sovereign power and the supporting mountains bow down to it depending on the ranking systems. So the reference does have some connotations of a hierarchical basis.

Rail: So in your own way, you are taking some of those structures and redoing them with a certain subtext that undermines them. At the same time, you reconstruct the space to address a new pictorial requirement, which is up against the surface of the picture plane, while allowing some depth to exist. As a result, the viewer feels this contradiction just as much as the people in the painting: they can’t go up the mountain; it’s like they are stuck where they are. Yet again, like scroll painting, you’re moving through and with the landscape.

Ji: Yes, that’s how I do my work as well. When I travel, I paint. I move from one little section to the next. The large sheets of paper are folded and refolded, and I work on small parts.

Rail: But in your head you must have some sense of how it will go together.

Ji: Very roughly, and it’s a long process. I spend weeks and weeks on a piece, and sometimes it would take one bad part, which may lead me to discard the whole thing. Other times I have to stay with it in order to bring some unexpected clarity to the piece. Even though I kind of work back and forth. But it’s impossible to simultaneously work in all these areas, so what I tend to do is work on one section, almost finish it, and then move onto another section.

Rail: In this new body of work, it seems to me that the scale has changed dramatically. These are the biggest paintings you have done so far, right?

Ji: Yeah, for this show I had the idea of really using the physical scale in relation to the body. For instance, when you look at a mountain, you’re looking from the bottom up. And sometimes the reverse happens. Ultimately your vision is unclear about what you’re looking at.

Rail: That’s true.

Ji: You can see similarly in the corner piece where we have the people walking from two directions, I deliberately painted them low, eye-level, so you can’t really look at all the details. In other words, you are aware that you are looking at one section of the painting while other things are moving at the same time. You kind of see one panel on the left wall, people moving from one direction, while you are looking at a group of people moving to another direction, on the right panel. Again, it’s all happening kind of simultaneously.

Rail: So you wanted simultaneity in that piece, in a sense that it’s much larger than you can even see or experience.

Ji: Yes. I imagine that there would be two people looking at one section at a time, usually from right to left on one side, and one side from left to right. And since they’re all opened up and coming together the corner wall, I felt that they should have a physical locality and the height that I intended.

Rail: But as far as the narrative aspect is concerned, your work doesn’t quite follow that tradition exactly. It is a narrative of desperation in a way. I mean there are ghosts in the form of people taking their whole lives with them. A certain internal migration, perhaps?

Ji: An internal migration and an abandonment of all these things. Another part that is important to me, which has never happened before, is this sort of industrial scale of moving people that has been orchestrated by the government.

Rail: Yeah, one and a half million people. That’s a huge number.

Ji: And the landscape is vast.

Rail: Can you talk a bit about your drawing?

Ji: For me, drawing is a way to get a hold of the detail that was important. Especially with this project, since these are fairly big pieces it’s necessary that they can defer to the drawings. And I don’t mind that. I sort of wanted to be a little bit more removed from the whole process.

Rail: You wanted to be more objective and less overtly satirical. Whereas, in the earlier work, there is a kind of grotesqueness to some of these figures, these new ones seem less so. Anyway, you said at one point that you were influenced by the German expressionists like George Grosz and Otto Dix. In what way do you relate to their work?

Ji: I like their work in a formal sense, the way they construct the figure with a certain Expressionistic pathos and contempt for their social and political conditions. Though in my work, the figures are portrayed more or less in despair and lost in their environment, which in this case, the surrounding landscape that connects to a long history in traditional Chinese painting as well as its culture. So there’s a sense of affection I have for them. If I want to describe a learned person in this very rustic landscape, there would always be some bamboos near him to indicate that he was the learned figure. It’s kind of hidden, but here and there you can see a fisherman, or a poet.

Rail: You had spoken about the tradition of the poet in relationship to the emperor, the poet being the one who can speak or write to authority.

Ji: From early on, the poet had an official post—he goes through the countryside and collects folk songs from the people; these songs reflected the true feelings of the people, like their complaints. The emperor had to do something to fix it, to correct his behavior and policy. So by the Hung dynasty I like that the poet had such power; but if he criticized the emperor too much, then the emperor got upset and sent him away to some remote province. So he became very angry, the poet.

Rail: So that’s the tradition you see yourself in some way. Do you think that the Misty poets, like Bei Dao, had to be indirect before they came to the West? You know the poets of post culture revolution, that first generation?

Ji: Yeah, very much like that.

Rail: Yeah, the Zigzag poets of the more recent tradition. The ones who stayed in China, the most recent generation, seem to be trying to find ways of being critical of the government and their society, but they have to do it in very round about ways. The whole thing with China, (we’ve talked about this,) is that everything has to be read between the lines.

Rail: There is a whole tradition of the commentators on the paintings, the commentators on the poets who develop or write on the painting that’s not equal to the painting. So when you say you’re trying to be more descriptive, you’re trying to be less directive. You’re not telling us how to read this.

Ji: No, not at all. It’s more about looking than anything else.