‘American’ names come in many forms

June 2, 2016 Updated: June 2, 2016 3:51pm

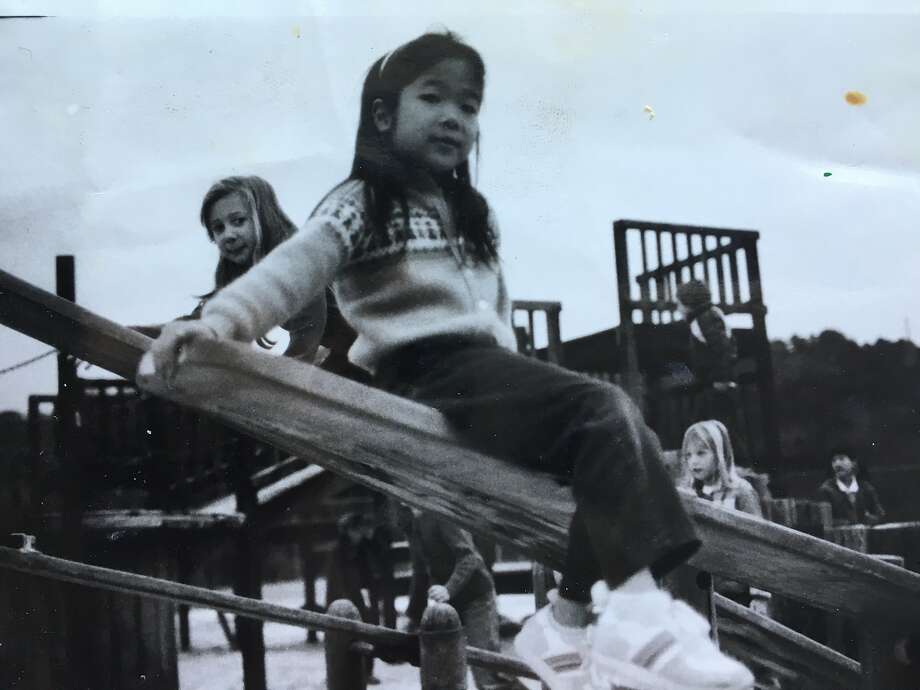

In the first or second grade, the principal mangled my last name during an academic-achievement award ceremony. I marched up in front of the school and announced, “It’s Hua! Not Hoo-aah.” Everyone laughed — even the principal — and I took my seat, pleased as a sassy kid in a television sitcom.

At the next ceremony, the principal mispronounced my name again. I corrected her — as I thought I was allowed to, as I thought I should. No one at school had told me otherwise, but this time, she turned me away.

I surely must have sunk into fear, shame and confusion, but the next moment I could remember was sitting in her office. “Correcting people isn’t nice,” she said. She handed me my award and shook my hand. She didn’t explain how and when I — a lowly kid — could have told her.

People mispronounced her name all the time, she said. Her message was clear: Don’t make a fuss. I wasn’t trying to be rude, but if the principal wouldn’t take the time to learn my last name — the name of my Chinese forefathers, the name my brother, my sister and my parents shared — why should anyone else?

In this season of graduations and final assemblies, students in the Bay Area and beyond may harbor similar fears. A new national campaign — My Name, My Identity — promotes respect for students and their diverse names and backgrounds. Educators can sign an online pledge, promising to pronounce students’ names correctly.

Chances are, if your last name isn’t Smith or Jones, people may mispronounce it. Some might think, lighten up, what’s the big deal, get over it, but tales of humiliation and anger have been pouring out on social media under the campaign’s #mynamemyid. They recount teasing by teachers and classmates, or being given another name or nickname against their will.

Launched by Santa Clara’s Office of Education, the National Association for Bilingual Education, and the California Association for Bilingual Education, the campaign through its website has already collected more than 1,200 pledges from more than 500 cities and nearly 300 school districts.

Learning to pronounce a name is another task in an educator’s unending day, but doing so can set the tone for how classmates treat a fellow student that year and beyond.

In my hometown, we were among a handful of Asian families. A few classmates declared open season on me, transforming the three letters of my last name into a high-pitched shriek of a kung fu master. “Hoo-aaaah! Hoo-aaah!”

They used my name against me, telling me I didn’t belong. A 2012 study contends that daily mispronunciations in K-12 schooling may make students feel inferior, lead to anxiety and resentment, and for some, may hinder academic performance.

Many educators already try to say names with respect and accuracy, to establish a rapport with their students and make them feel welcome. Mandy Stewart, an assistant professor of bilingual and ESL education at Texas Woman’s University, tweeted: “Because my students are worth me saying their name correctly!”

It may take a few tries, but students appreciate the effort. More than a century ago, immigrants may have felt compelled to change their names — or had their names changed for them — erasing generations of history and identity. You weren’t supposed to look back, but today, our gaze travels around the world. Opportunities go to those who can think beyond borders, those who can befriend, learn from and work with people whose histories and whose names differ from their own.

Asian Americans are the country’s fastest-growing racial group. By 2040, nearly 1 in 10 Americans will be of Asian descent, demographers predict, and last names such as Zhang, Gupta or Autufuga could become more common.

At my middle school graduation, though I was excited to wear my lacy white Gunne Sax dress and clip my hair in a puffy bow, I dreaded the catcalls that my family would hear. It’s been a long time since anyone made fun of my last name, but even now I grapple with when — or if — I should explain the pronunciation: “Wah, like W-A-H” or “Hua, like the end of chihuahua.”

In Chinese, the character for my name is built into the Middle Kingdom’s formal designation: zhong hua ren ming guo. To be a Hua is to be Chinese. To me, it’s also what it means to be American.

When you ask people how to say their names, it’s a chance for cultural exchange, a chance to hear their stories. What’s yours?

Vanessa Hua’s column appears Fridays in Datebook.

My name gets mispronounced all the time but it does not make me feel inferior.

I had a Chinese girlfriend who was born in Vietnam she was named Peace which is pronounced WAH but is spelt Hoa. I was with her at some union meeting where the head of the union pronounced her name HO AH. Fair enough, but she was also Chinese and even though American born, should have had a bit of a clue or should have asked, especially since this was Local 2 where nearly all the members were immigrants.

~~

华裔作家:中国姓让我在美国从小受尽嘲弄(图)

华裔专栏作家瓦妮莎•华(Vanessa Hua,音译)2日在《旧金山纪事报》(San Francisco Chronicle)撰文,谈到自己的姓氏从小带给自己的困扰。文章编译如下:

一到二年级的时候,学校校长有一次曾在学校的颁奖仪式上把我的姓读错。然后在我上台领奖的时候,我对所有人说道:“我姓华,不是呼哈(Hoo-aah)。”所有人都笑了起来,包括校长。

然后在下一次仪式上,校长又一次读错了我的名字。我也再一次没有顾及的纠正了她,因为我认为自己应该这么做。不过这一次,她批评了我的做法。

我当时肯定有些害怕和困惑,不过还记得的是我坐在她的办公室里,“当众纠正别人可不好。”她说道,然后将奖品递到我的手中。但是却没有告诉我,应该在什么时候,或者怎么样去告诉她我的姓氏的正确发音。

人们也总是叫错她的名字,她说道。她的意思很清楚,不要为此大惊小怪。我不是不礼貌,但是如果我的校长都不花时间了解我的姓氏,那么其他人会怎么做呢?

又到了毕业季的时候,旧金山学区的学生们可能会面临跟我那时候一样的窘境。现在一项名为“我的姓名,我的身份”的新的全国性活动正在推出,督促对学生们姓名以及身份背景的差异性予以尊重。教育工作者们可以在线签署一份承诺,答应正确叫出学生们的名字。

有人可能会认为这没有什么大不了。不过,在社交媒体上发起的#mynamemyid话题下,已经涌现出了很多对此的抱怨。他们都容忍过老师或者同学的嘲笑,甚至会因此被冠上绰号。

这一活动由圣克拉拉教育办公室(Santa Clara’s Office of Education)、全美双语教育协会(the National Association for Bilingual Education)、加州双语教育协会(California Association for Bilingual Education)联合发起,目前在500多座城市和近300个学区募集到了1200多份承诺签名。

虽然说对繁忙的教育工作者来说,学习如何正确叫出这些名字,意味着给他们增加负担,但是同时也会让师生间对彼此更为尊重。

2012年的一份调查显示,在我们的基础教育中,这种做法会让学生出现自卑、焦虑、怨恨等负面情绪,更有甚者还会严重影响到他们的学习。

一个多世纪以前,移民为了尽快融入新环境会选择改名字,来消除与周围人的陌生感。但是现在,情况已经有了变化,那些眼光越过了身份障碍、懂得求同存异的人才能获得更多机会。

作为美国人口数量增长最快的少数族裔群体,预计到2040年,美国人口中有十分之一会有亚洲血统,到时候张、古普塔(Gupta,印度姓氏)等等类似的姓会变得越来越普遍。

虽然现在已经没有什么人再取笑我的姓,但是有时候还是免不了费一番口舌向他们解释到底该如何正确发音。华姓在中文里代表着中国人的意思,但是对我来说,这个姓氏同样意味着我的美国人身份。