历史上有些冲突非得武力解决不可,如始皇帝要统一天下,不过一旦诉诸武力,难免生灵涂炭,所以孙子说不战为上策。

不过历史上不必要动武却动了武的事件就更多了,现在回想起来,以前古时大家说打就打,是愚昧,脑子没开窍,不见棺材不掉泪。可是脑子开窍了并不意味着做事就理智了,精英权贵们杀起人来眼睛不不眨,最典范的例子,莫过于一战(第一次世界大战)。

【当然,时代进步了并不意味着大家更理智了,人类的同情心就增加了。不久前,西方大肆声讨“共产主义国家”以“人民”的名义造成大规模的死亡(这点中苏和其他小兄弟解释不清),可是另一方面,二战后世界上多少真正的动刀动枪的战争是美国引起的,造成的毁坏是多少?现在整个中东不就是美国摧毁的吗?也难免有人攻击美国搬起石头砸自己的脚,直接引发极端伊斯兰组织。】

一战,是白人“文明“间的较量,大家都是基督徒,杀起来好像心里想的都是基督,开战后全欧洲爱国情绪高涨,然而一战却是最莫名其妙,最愚蠢的人类自相残杀。

当时欧洲工业革命已结成硕果,生活水平,社会环境,科学艺术技术创新和大规模工业生产,已经达到一个世纪前不可想象的水平,而且全世界通讯也非常发达,贸易遍布全球,欧洲工业也密切相关,互相依赖,虽然各国之间的竞争很激烈,尤其是殖民地和世界市场的争执(大家如果在中国接受教育,大概给熟悉“帝国主义、殖民主义历史”),比如英国海军和德国海军的军备竞赛,很危险,不过所有人都觉得不会打,不可能打,也不愿打,反应到当时的社会是一片享乐的气氛。

可是一战还是打起来了,两千万人死,两千万人伤,毁坏就更大了,连远离欧洲的中国也陷在里面,因为新的势力要抢旧的势力,中国只是个战利品。打的原因,就是各国彼此间的统治阶层盲目地宣扬仇视他国、好战的情绪,言语越来越激烈,到了被自己逼到毫无退路的环境,结果一个“意外”(意外事件其实是必然发生的事件)但悲剧式的事件就引发了文明世界相互残杀的恐怖剧。

用今天通俗的话来说,就是大家高呼口号,互相不让步,不给对方面子,不给对方台阶下,话都说死了,结果来个意外,大家除了动枪别无选择,因为那是你自己的“面子”已经无法放得下(所谓“面子”,西方称之为“尊严”,dignity,“面子”是西方贬低中国的词——虽然他们也用于自己——就是自己执政的合法性),这主观选择对立的策略,尽管完全可以避免,最后也只能将大家带上战场。

美国对中国制裁是出于中国在“西方制度、体制”内用种种手腕利用“非法占利”的回应,然而关税不仅是下策,在规矩的范围内还是最不公平的惩罚,不过这是美国总统的智力唯一能想到的。中国嘴上说要改善,但迟迟没有行动,现在一旦被攻击,觉得只能反击(否则习近平“人民领袖”的形象如何下台?);淳朴(Donald Trump,人称特朗普或川普)恰如一个中学霸王,只能阿谀逢迎,哪能冲撞?结果加码,你不是要打吗?打。

习近平咋办?只能跟上。商业部已经表态了,“奉陪到底”,双方的交涉也终止了,整个陷入僵局。

在白宫,美国政府已经没有任何制衡的力量。所有所谓“理智”的人物都已经被赶走了,剩下的要么是跟淳朴想的一样的,要么是不敢说话的,要么是跟屁虫。

在中南海,中国政府同样已经没有任何制衡的力量,别说国务院人大,即使政治局常委,也已经是形式的。李克强现在难道不是像俄国总理梅德韦杰夫似的,只是给大家照相的?

如果说淳朴是给自己中学霸王的意识支配着,那习近平就是给自己的救世主思维主宰着。两者似乎天壤之别,效应却未必有差别,那就是两个霸主,不论理智或非理智,为了“得胜”,为了“本国利益”,把世界机器引向灾难性结局。

这场灾难性的“游戏”有个大家忽略的危险因素,就是全世界(中国美国欧洲日本等等)都认真研究习近平的一言一行,觉得他说啥是啥,然而没人把淳朴说的话当真,觉得他是是咋呼,是初等“交易”(谈判)伎俩。不过,当两头公牛较上劲后,当真也好,不当真也好,不见血难有什么结局。

President Trump created confusion within his administration and abroad because of a negotiating style you could call "governing by bluffing":(Axios)

He threatened to veto a spending bill that conservatives hate, then signed it.

He announced stiff tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum, then the administration started negotiating tons of carve-outs.

He talks of war with North Korea, then agrees to meet with Kim Jong-un.

He muses openly of replacing top aides, including White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, then lets them stay.

大家都觉得淳朴其实会降价的。真的吗?

历史都一样,民众觉得这世界太不公平了,觉得霸王能改变现状,还给自己应有的权益,而几个霸王自觉代表全民,一举一动都是必要的措施,结果一步一步走向不可逆转的灾难。

蠢。

《金融时报专栏》狼马(Martin Wolf)

2018.04.08

The Chinese economy is rebalancing, at last

The Chinese economy is rebalancing, at last

We are seeing a necessary change towards more reliance on consumer demand

Consumption is at last becoming the most important driver of demand in the Chinese economy. This is a long-awaited and desirable adjustment. It promises to shift China away from its excessive reliance on inefficient, debt-fuelled investment. But it still has a long way to go. As the shift is being completed, the country will need to manage an overhang of bad debt. But the adjustment has begun.

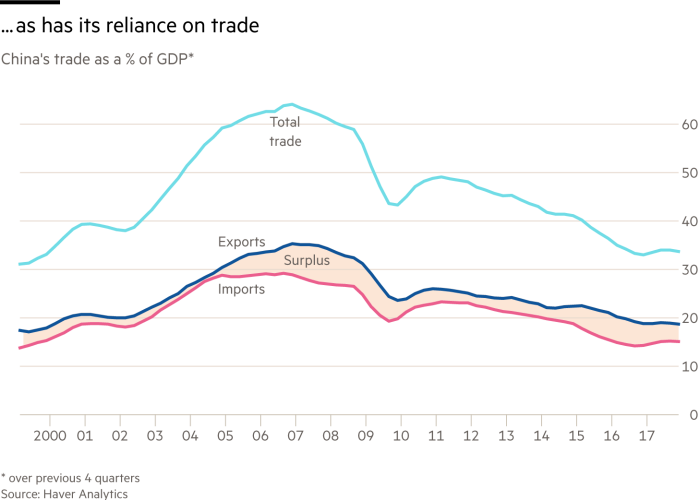

In 2007, premier Wen Jiabao argued rightly that “the biggest problem with China’s economy is that the growth is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”. In that year, gross national savings were 50 per cent of gross domestic product, up from 37 per cent in 2000. These huge savings financed domestic investment of 41 per cent of GDP and a current account surplus of 9 per cent.

Then came the global financial crisis. The Chinese authorities promptly realised that the current account surplus had become unsustainable. In the short run, the only way to avoid a slump was to expand investment further. In 2011, gross investment reached 48 per cent of GDP and the current account surplus fell to 2 per cent. But national savings remained at 50 per cent of GDP. (See charts.)

This solution brought new problems. The first was a declining return on investment. The simplest way of showing this is via the incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR), which measures the amount of investment needed to generate a given increase in output. This has roughly doubled since 2007. That is not surprising: the investment rate has jumped, while growth has nearly halved. Moreover, the rise in the ICOR may well understate the true decline in returns: as Michael Pettis of Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management argues, useless investment does not contribute to GDP.

The second problem is that the increased investment was driven by a huge rise in debt. According to the Institute of International Finance, gross debt rose from 171 to 295 per cent of GDP between the fourth quarter of 2008 and the third quarter of 2017. This is very high for an emerging country. Moreover, half of the increased debt went to non-financial corporate entities, which did much of the increased investment. A substantial portion of this increased debt may prove to be bad. Starting from the dramatic rise in the credit-dependence of growth, London-based Enodo Economics argues that the needed debt write-offs might ultimately amount to 20 per cent of GDP. This might seem big. But it would be manageable for a creditor country with a largely closed financial system.

Up to 2014, then, nothing had happened to make the Chinese economy seem any less unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable. On the contrary, China had merely replaced an excessive current account surplus, with still more excessive investment, soaring debt and property bubbles. The past three years have witnessed change at last: investment has fallen by 3 per cent of GDP, while public and private consumption have risen by much the same proportion. As a result, consumption has become a more important source of additional demand than investment. Thus, in 2017, notes a background paper to this year’s China Development Forum, final consumption contributed 59 per cent of GDP growth. As investment growth has declined at long last, the rise in indebtedness has also (apparently) stopped.

Behind this has been a willingness to substitute quality for quantity of growth. Explanations for this willingness include the shrinkage of the labour force and a slowing of the rate of rural-urban migration. The increasingly service-driven economy of today is also more employment-intensive than the heavy-industry driven economy of the past. With the labour force now shrinking and growth more employment intensive, real wages have soared, raising the share of labour in national income. Enodo Economics argues that in 2015 the share of household disposable income and labour compensation were already higher than in Japan and South Korea.

It is only because the household savings rate is still very high in China that private consumption is so low a share of GDP. As ageing takes hold, that is likely to change, possibly quite quickly. If the government were to provide an adequate safety net and better health and education services, as well, the household savings rate might fall sharply. If so, the investment rate could also shrink to a more appropriate level. After all, it is still substantially higher than it was in 2007, let alone 2000.

In brief, while the shifts are slow and the full adjustment to more reasonable levels could take until the middle of the next decade, we are seeing early signs of the necessary change in the structure of the Chinese economy towards one that is less unbalanced and, above all, one that is more reliant on the consumer demand of China’s vast population. That would, in turn, be good for China and for the rest of the world.

Good policy could also accelerate the shift, by increasing the transfer of profits to the people, via ownership, taxation or, better still, a bit of both. It is more or less inevitable that a clean up of excessive debt will also be needed, together with substantial reform of the financial sector. But that would also become far easier if the huge imbalances — above all, the excessive reliance on investment — were at an end.

The chances of achieving desperately needed rebalancing and even of managing that transformation fairly smoothly are rising. The story told by former premier Wen is far from over. But we can now at least envisage a happy ending.

2018.03.27

How China can avoid a trade war with the US

How China can avoid a trade war with the US

Beijing must recognise the shift in American perceptions and make some concessions

How should China respond to Donald Trump’s aggressive trade policy? The answer is: strategically. It needs to manage a rising tide of US hostility.

Of the events in Washington last week, the appointment of John Bolton as the US president’s principal adviser on national security may well be more momentous than the announcement of a “section 301” trade action against China. Nevertheless, the plan to impose 25 per cent tariffs on $60bn of (as yet, unspecified) Chinese exports to the US shows the aggression of Mr Trump’s trade agenda. The proposed tariffs are just one of several actions aimed at China’s technology-related policies. These include a case against China at the World Trade Organization and a plan to impose new restrictions on its investments in US technology companies.

The objectives of these US actions are unclear. Is it merely to halt alleged misbehaviour, such as forced transfers — or outright theft — of intellectual property? Or, as the labelling of China as a “strategic competitor” suggests, is it to halt China’s technological progress altogether — an aim that is unachievable and certainly non-negotiable.

Mr Trump also emphasised the need for China to slash its US bilateral trade surplus by $100bn. Indeed, his rhetoric implies that trade should balance with each partner. This aim is, once again, neither achievable nor negotiable.

The optimistic view is that these are opening moves in a negotiation that will end in a deal. A more pessimistic perspective is that this is a stage in an endless process of fraught negotiations between the two superpowers far into the future. A still more pessimistic view is that trade discussions will break down in a cycle of retaliation, perhaps as part of broader hostilities.

Which it turns out to be also depends on China. It must recognise the shift in US perceptions, of which Mr Trump’s election is a symptom. Moreover, on trade, the Democrats are far more protectionist than the Republicans. What are the forces driving this shift? China’s rise has made the US fear the loss of its primacy. China’s communist autocracy is ideologically at odds with US democracy. What economists call “the China shock” has been real and significant, although trade with China has not been the main reason for the adverse changes experienced by US industrial workers. The US has also failed to provide the safety net or active support needed by affected workers and communities.

Furthermore, the deal reached when China joined the WTO in 2001 is no longer acceptable. As Mr Trump states, the US wants strict “reciprocity”. Finally, many business people argue that China is “cheating”, in pursuit of its industrial objectives.

Experience shows that the complaints will never end. A decade or so ago, complaints were about China’s current account surpluses, undervalued exchange rate and huge accumulations of reserves. All these have now been transformed: the current account surplus itself has fallen to just 1.4 per cent of gross domestic product. Now complaints have shifted towards bilateral imbalances, forced transfers of technology, excess capacity and China’s foreign direct investment. China is successful, big and different. Complaints change, but not the complaining.

How might China manage these frictions, exacerbated by the character of Mr Trump, yet rooted in deep anxieties?

First, retaliate with targeted, precise and limited countermeasures. Like all bullies, Mr Trump respects strength. Indeed, he respects China’s Xi Jinping.

Second, defuse legitimate complaints or ones whose redress is in China’s interests. Liberalising the Chinese economy is in China’s own interests, as the astonishing results of 40 years of “reform and opening up” demonstrate. China can and should accelerate its own domestic and external liberalisation. Among the widely shared complaints of foreign businesses, is over pressure to transfer know-how as part of doing business in China. Such “performance requirements” are contrary to WTO rules. China needs to act decisively on this.

Third, make some concessions. China could import liquefied natural gas from the US. This would reduce the bilateral surplus, while merely reallocating gas supplies across the world. But doing the same thing for commodities in which China is the world’s dominant market would be far more problematic, since it would hurt other suppliers. Mr Trump may well want China to discriminate against Australian foodstuffs or European aircraft. That way lies the end of the liberal global trading system.

Fourth, multilateralise these discussions. The issue of surpluses in standard products like steel cannot be dealt with at a purely unilateral or bilateral level. As a rising global power, China could play a central role in trade liberalisation, thereby strengthening the system and increasing the world’s stake in the health of the Chinese economy. Operating at such a global level brings another potential benefit: it is hard for great powers to negotiate bilaterally, since they tend to view concessions to each other as humiliating.

In the global context, however, a concession can be seen as a benefit to everybody. Finally, by operating under the rubric of the WTO, China puts Europeans in a difficult position. Europeans share US anxieties over China’s policies on intellectual property, but they also believe in the rules. If China took the high road, Europeans might feel compelled to support it.

We are in a new era of strategic competition. The question is whether this will be managed or lead to a breakdown in relations. Mr Trump’s trade policy is a highly destabilising part of this story. China should take the longer view of it, for its own sake and that of the world.