CHINA, INTERNATIONAL EYE April 5, 2018

Britain Must Look to China to be Great Again

https://stanfordsphere.com/2018/04/05/britain-must-look-to-china-to-be-great-again/

At the last G20 summit, Xi Jinping informed Theresa May that Britain and China must ‘shelve their differences’ over Hong Kong. Xi could not be more correct. Britain has been in a state of perpetual decline since its superpower heyday in 1914. During the 20th century, Britain ceded its empire and global status without formulating a new role on the global stage. Britain’s historically backward outlook suddenly appeared to shift in 2015 with the declaration of the creative and forward-looking ‘Golden Age’ of British-Chinese relations. Predictably, Britain has since backtracked. To prevent a directionless twenty-first century, Britain must look back to China.

The tale of British twentieth century decline is vast and tortuous. Looking at both ends of the century, in 1914, Britain was the global superpower, possessed the world’s largest empire, and the pound sterling was the world’s dominant currency. But by 1990, Britain was reduced to a small island off the coast of Europe.

The years 1914-1945 marked the start of Britain’s decline. During this period, America superseded Britain as the world’s foremost superpower, and the dollar usurped the pound as the dominant currency. Britain further amassed vast debts with the Second World War, alone responsible for £21 billion in debt. Nevertheless, Britain remained profoundly influential on the world stage. Indeed, Britain’s empire was at its peak in 1945, covering 20% of the world’s population. However, Britain’s empire would soon disintegrate.

The collapse of the empire started with Indian independence in 1947. Not only was India Britain’s largest colony, it was also seen as the ‘jewel in the crown.’ After this profound loss, the famous ‘winds of change’ became all but inevitable, and subsequently swept across the Global South. From the late 1950s onwards, vast swathes of the previously colonized world gained independence. The process of decolonization came to an end in 1984 when Britain agreed to give Hong Kong back to China. This decision marked the end of Britain’s Empire, an empire which had taken three centuries to build, had been dismantled in just 37 years but for a few marginal islands.

Having lost its empire, Britain now had to forge a new role in world politics. No new coherent role has ever emerged. Successive governments entirely failed to show any creative or forward-looking thinking, instead reverting to old and out-dated paradigms. Britain first sought to maintain its superpower status through the so-called ‘special relationship’ with America. On certain fleeting occasions, this appeared a smart approach. For instance, the 1962 Nassau agreement between John F Kennedy and Harold MacMillan enabled the UK Polaris program, a key nuclear development. However, America’s invasion of Grenada in 1983 demonstrated that talk of a ‘special relationship’ was largely specious. Washington decided to invade a Commonwealth country without consulting the British. Most troublingly the ‘special relationship’ primarily served as a means for Britain to delude itself into believing that it maintained significant global power; that Britannia still ‘ruled the waves.’ This was palpably untrue.

Rather than the fanciful ‘special relationship,’ a role as a leading European power was Britain’s natural progression post-Empire. This could have guaranteed an important global position for decades to come. The European economy was large and growing rapidly right on Britain’s doorstep, but Britain’s leaders were never able to accept this logic. They were accustomed to thinking of Britain as a superpower or as an empire rather than as a European power. Moreover, the British view of the continent was tainted by centuries of a deeply-held island mentality. Whilst West Germany and France had realized the potential of a pan-European project as early as 1951 with the European Coal and Steel Community, the British only joined the European Economic Community in 1973 and subsequently proved very reluctant Europeans. In particular, Thatcher’s aggressive approach towards Europe solidified the perception of Britain as an unwilling and ‘bad element’ of the EEC, thereby diminishing British power on the continent. Had Britain sought a European role earlier, or shown greater commitment to the EEC, the U.K. could perhaps now be playing a role similar to that of France or Germany. Britain’s profound failure to discard old modes of thought prevented it from ever assuming a leading European role.

By 1990, Britain had seemingly lost all its former means of power. The primary losses were the Empire and its economic strength on the world stage. Particularly damaging, though, was its utter failure in the period 1945-1990 to discover a new role. Throughout the twentieth century, Britain acted like a forlorn lover, desperately searching for a new flame, but never letting go of his past love.

From 2014-2016, this decline reached its peak. First, the ‘United’ Kingdom’s own union was threatened by the 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum. More significantly, leaving the EU in 2016 was the culmination of this long-term decay. Having lost its superpower role, its empire and its ‘special relationship,’ Britain promptly decided to abandon its position within Europe. Troublingly, the rhetoric of many pro-Brexit figures indicated that, despite the experience of the twentieth century, Britain is still stuck in old paradigms. Rhetoric surrounding ‘sovereignty’ harked back to the 19th century when Britannia ‘ruled the waves.’ We are thus in the midst of a century-long crisis of British identity and direction. The famous United States Secretary of State, Dean Acheson, commented in 1962 that ‘Great Britain has lost an Empire and has not yet found a role.’ This rings even truer now than in 1962.

However, for a brief period in pre-Brexit 2015 this appeared to have changed. The then-Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne defied the gravity of Britain’s past century of foreign policy logic. Shockingly, they looked to China as well as Europe. Osborne talked of a ‘Golden Age’ of British-Chinese links and aimed for China to become Britain’s second largest trading partner by 2025. British leaders were thinking creatively about the country’s global role. There was significant basis for this dual focus on China and Europe; although most of Britain’s trade is with Europe, the European Union has exhibited far slower growth than developing economies over the past decade. By contrast, China has consistently grown by 7% per annum over the past few years and looks set to pass the size of America’s economy in the near future. Cameron and Osborne were looking to new avenues rather than reverting to the old, outmoded paradigms. At long last!

This should have marked the start of a serious reformulation of Britain’s world role. Sadly, this was not to be and Britain reverted back to old ways of thinking. The leadership change from Cameron-Osborne to Theresa May following Leave’s victory in the EU referendum heralded a more backward-looking vision of Britain’s global role. Two leading candidates have emerged out of all the talk surrounding the endless free trade deals Britain would sign post-Brexit. First, Australia. This makes a mockery of May’s ‘global Britain’ vision; Australia is a former colony and is only the world’s 13th largest economy. Even worse, America seems to have become Britain’s greatest hope post-Brexit. This was a retreat into the Anglo-Saxon world. May has recently talked about the ‘special relationship.’ This is vacuous British thinking at its worst from a leader who lacked any democratic mandate pre- or post-election 2017. As discussed, even at its height the ‘special relationship’ was merely a means for Britain to delude itself into believing it maintained superpower pretentions and to protect itself from realizing the reality of deep decline. Moreover, America has profoundly changed in the half-century since the height of the supposed ‘special relationship.’ Far from its peak, America is facing serious political decay and is led by Trump, who threatens the integrity of American liberal democracy. Now is certainly not the time to move closer to America.

Even worse, Britain appears to have abandoned the prospect of a ‘Golden Age’ of Chinese relations when this looked to be one of the best options post-Brexit. This was firstly expressed in May’s attitude toward the development of the nuclear power station Hinckley Point. May initially halted construction due to unfounded suspicions that Chinese investment could present a security threat. This echoed the worst vestiges of the ‘yellow peril’ and was a serious backward step from Osborne’s far-sightedness. Secondly, tensions have arisen between the two countries over Hong Kong, with Britain arguing that the ‘one country two systems’ framework is supposedly disintegrating. Xi is completely right that China and Britain’s differences on this issue must be ‘shelved.’ An issue as unimportant as Hong Kong must not be allowed to complicate Britain’s future role on the world stage. Moreover, Britain’s criticism of China’s failure to introduce democracy to Hong Kong reveals a deep historical amnesia .During Hong Kong’s 155 years as a British colony, all 28 governors were appointed from 6000 miles away in London. So much for democracy!

Britain has also distanced itself from China on the basis of human rights infractions. This is another serious case of historical amnesia. Britain prided itself on the ‘special relationship’ with a country that continually funded autocratic states such as Saudi Arabia and overthrew democratically elected governments such as Allende’s Chile and Mossadeq’s Iran. Moreover, in recent years America has directly violated human rights in Guantanamo Bay. This reveals a severe double standard in Britain’s foreign policy.

Britain must get over itself. May, or preferably Corbyn’s, government must think creatively to forge a role for Britain in the twenty first century. Rather than constantly reverting to outmoded paradigms, Britain must move closer to China and Asia, and look to the fastest growing countries rather than the old, declining world. Ideally, it must present itself as the gateway to Asian and Chinese trade. This would make the most out of a very difficult situation post-Brexit and would involve completely rethinking Britain’s identity and role in the world. But this is exactly what Britain has avoided since 1914.

Moving closer to Asia and China is Britain’s best hope for a return to greatness: showing the ability to carve a unique and pioneering role in world affairs. Alternatively, if Britain fails to think creatively about its identity and future, it will be resigned to a directionless twenty-first century.

Ravi Veriah Jacques

An earlier edition of this article was published in guancha.cn

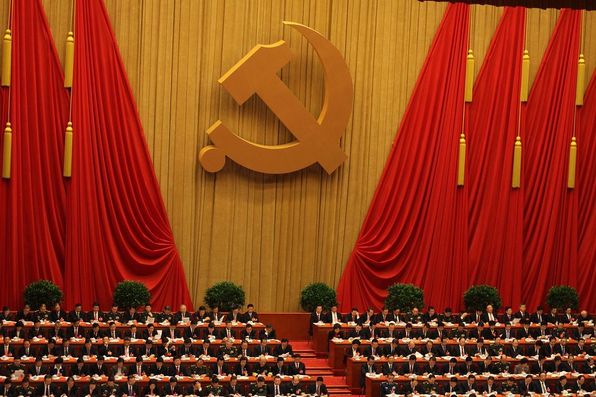

Photograph: 18th National Congress of the Community Party of China, 11th November 2012. Credit: Dong Fang