澳学者:澳大利亚必须停止敌视中国

湖北荆楚网 2022年11月20日21:53 来源: 参考消息网

http://news.cnhubei.com/content/2022-11/20/content_15248166.html

参考消息网11月20日报道 英国《卫报》网站11月15日文章发表题为《澳大利亚要想修复与中国的关系,必须停止敌视中国》的文章,作者是澳大利亚悉尼大学中国近代史高级讲师戴维·布罗菲。

全文摘编如下:

尽管人们对中澳领导人的会晤充满期待,但从工党那里很难得到除了制式文件以外的有关中国的信息。澳大利亚外长黄英贤在13日的一次演讲中称,我们将“在能合作的方面合作……在必要的方面存在分歧”。那么工党的对华政策到底是什么?

自上台以来,工党已经宣布希望“稳定”与中国的关系。这是一个模棱两可的词语,或许有意为之,以让不同的选民用自己的方式进行解读。对中澳关系乐观主义者来说,稳定将被视为一种改善;对华鹰派人士则把该词解读为巩固两国紧张关系的新常态。这个概念有什么实质内容吗?

从堪培拉的角度来看,亚洲的最理想情况看起来大体上一直如此:在美国的钢铁之墙后面,澳大利亚的出口源源不断地流向中国。当这堵墙开始显露弱化的迹象时,澳大利亚政府就会故意引导我们转过来将中国说成敌人,试图让美国牵头的遏华行动更坚定。这里的结论是,当美国步步为营的时候,澳大利亚就避免让自己太出风头。

堪培拉可能觉得在这种环境下可以避免枪打出头鸟的风险,或许还可以获得一些回旋的余地,以防美国遏制中国崛起的努力失败。如果说“稳定”在政策方面有什么意义的话,指的就是这点。

然而,事实是,工党仍然坚持最初让我们走到这一步的一整套政策。虽然澳大利亚媒体现在焦急地期待外交裂痕修复的迹象,但就在几周前,新闻头条还在欢呼B-52轰炸机抵达北部地区。澳英美联盟已经让我们走上一条与美国不断深化军事融合的道路。当我们公开为了针对一个国家而武装自己时,呼吁与之建立“稳定”关系的意义何在?

一系列以中国是敌对的危险国家为前提的举措仍然存在。仅举两个例子,对中国投资的荒谬限制,以及对从事澳大利亚研究的中国学者实施签证禁令。

与含糊其辞的“稳定”相比,取消一些这种不利措施将给澳大利亚外交官一个更好的切入点来向中国表达不满。然而,悲哀的是,一些对华鹰派人士把任何的政策变化都描述为对北京做出的不可容忍的让步。

我并不是第一个指出这种言论的反常后果的人士:我们的政策视中国的态度而定。北京若是反对澳大利亚某项新举措,必定会促使我们强化该举措。这是我们需要摆脱的思维习惯。

当人们对国际外交的激烈交锋极为感兴趣时,这样说似乎有些奇怪,但我们需要多想想希望澳大利亚成为什么样的国家和社会。澳大利亚对中国的军事化回应正在加剧全球分歧,并分裂我们自己的社会。简而言之,正在破坏稳定。

反对这种未来的境遇与迎合北京无关。相反,正视澳大利亚自身对当前紧张关系的推波助澜作用,是与北京展开严肃对话的唯一可靠途径。

If Australia wants to mend relations with China, we must stop viewing it as the enemy

David Brophy, 15 Nov 2022, Dr David Brophy; MA PhD Harvard

Senior Lecturer in Modern Chinese History; Department of History

+61 2 9114 0778 Fax +61 2 9351 3918

david.brophy@sydney.edu.au

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/nov/15/if-australia-wants-to-mend-relations-with-china-we-must-stop-viewing-it-as-the-enemy

What is the point of calling for 'stable' relations with a country while we openly arm ourselves for war against it?

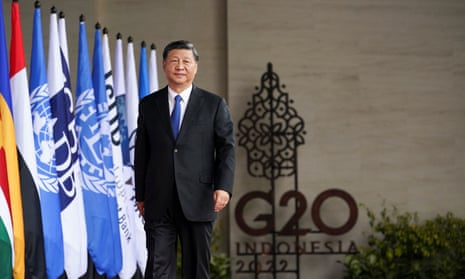

‘Australia’s militarised response to China is exacerbating global faultlines and fracturing our own society; it is, in a word, destabilising.’ Photograph: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

‘Australia’s militarised response to China is exacerbating global faultlines and fracturing our own society; it is, in a word, destabilising.’ Photograph: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

So what exactly is Labor’s China policy?

In opposition, Labor stood alongside the Coalition’s every move, only grumbling when the government descended into partisan point-scoring. Since coming to office, it has declared its desire to “stabilise” relations with China. It’s an ambiguous term, probably deliberately so, allowing different constituencies to each put their own spin on it. For Sino-Australian optimists, stabilisation will be seen as an improvement. China hawks interpret the term as consolidating a new normal of heightened tensions, with possibly a little less dog-whistling.

Is there any substance to the concept?

From Canberra’s point of view, the best-case scenario in Asia has always looked roughly the same: a world in which Australia directs an endless flow of exports to China from behind a wall of American steel. It was when that wall started showing signs of weakening that the Coalition led us on a deliberate turn towards talking up China as an enemy, in an effort to catalyse a more determined American-led containment effort.

The corollary here is that when America looks to be stepping up, Australia need not keep itself in the spotlight. Biden is doing enough now to signal a renewed American commitment to containing China. His most recent tranche of hi-tech export controls has convinced even skeptics that Washington is embarked on a policy of slowing China’s economic growth.

In this situation, Canberra may sense an opportunity to undo a little of the damage incurred while putting itself “out in front” (as Malcom Turnbull’s insiders termed his shift), and maybe also gain some wriggle room in case US efforts to stymie China’s rise fall flat.

If “stabilisation” has any meaning in policy terms, it is this.

The fact is, though, that the ALP remains committed to the whole suite of policies that got us here in the first place. While the Australian media now anxiously anticipates signs of repair to the diplomatic rift, only a few weeks ago headlines were hailing the arrival of B-52s in the Northern Territory. Whether or not the submarines ever eventuate, Aukus has put us on a path towards ever-deepening military integration with the US, all aimed at China.

What is the point of calling for “stable” relations with a country while we openly arm ourselves for war against it?

A series of measures premised on the notion of China as a singularly hostile, dangerous country, remain in place: absurd restrictions on Chinese investment, visa bans on Chinese scholars of Australian studies, to name two examples. The accompanying rise in anti-Chinese racism has been well documented.

Rolling back some of this harmful legacy would give Australian diplomats a far better entry point to air their grievances with China than vague talk of “stabilisation”. Sadly, though, some China hawks have succeeded in framing any change to today’s policy settings as an intolerable concession to Beijing. That being the case, Albanese is likely to bring little concrete to the table in his meeting with Xi today.

I’m not the first to point out the perverse consequence of this kind of rhetoric: that our policies do end up being determined by China. Beijing’s opposition to a new Australian move all but ensures that we double down on it. It’s a habit of mind we need to get out of.

At a time of heightened interest in the cut-and-thrust of international diplomacy this may seem an odd thing to say, but we need to worry less about what China thinks, and more about the kind of country and society we want Australia to be. Australia’s militarised response to China is exacerbating global faultlines and fracturing our own society; it is, in a word, destabilising.

Yes, China is moving in a more authoritarian direction under Xi. But prolonged tensions between China and the west will see concerns with human rights jettisoned on both sides. The recent race to arm strongman Manasseh Sogavare’s Solomon Islands police gives us, in microcosm, a picture of what a future of regional rivalry looks like.

Opposing this vision of the future has nothing to do with pandering to Beijing. On the contrary, confronting Australia’s own contribution to current tensions is the only credible way to start a serious conversation with Beijing about its.

David Brophy

David Brophy is a senior lecturer in modern Chinese history at the University of Sydney and an author

China is far from alone in taking advantage of Australian universities’ self-inflicted wounds

Having long encouraged universities to find funding elsewhere, politicians now home in on their ties to China to argue that they’ve lost their way

Sanctions only escalate tensions. It's time to tackle the Uyghurs' plight differently

We have to make a credible case that western opposition to China’s policies is not geopolitical manoeuvring, says Australian academic David Brophy