Aug 18, 2022, Nigeria sees China as a steady partner and its largest lender

https://merics.org/en/nigeria-sees-china-steady-partner-and-its-largest-lender?

How China Lost Nigeria

https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/how-china-lost-nigeria/

Even as China built up its influence, it remained deeply vulnerable to negative counter-narratives from the United States. That’s the paradox of hegemony.

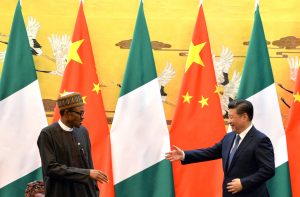

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, left, and Chinese President Xi Jinping reach for shaking hands during the signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing Tuesday, April 12, 2016

Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, left, and Chinese President Xi Jinping reach for shaking hands during the signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing Tuesday, April 12, 2016China is currently being hit in Nigeria by a burst of discontent whose outcome is still uncertain. Triggered in late July 2020 by what has become known as the “sovereignty clause” controversy in loan agreements between Nigeria and China, the discontent has, however, a longer history. The current backlash draws mainly on anger over the timeline of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China dateline; questions about Huawei’s participation in 5G networks; claims of uniquely Chinese racial practices against Nigerians; and the image of “China in Africa” more broadly.

The intensity and magnitude of the discontent means that this cannot be dismissed. Finger-pointing letters to the editor in Nigerian newspapers talking about “Nigeria’s Abusive Marriage With China and Slave Agreements” and opinions asserting that “it is unacceptable that our forefathers fought the White Man to liberate our continent only for our generation to hand over our hard-won liberties to barbarian hordes from Asia” are important signals. But, if it is not typical and cannot be dismissed, then the question of where it might be coming from arises.

The evidence indicates the phenomenon cannot be divorced from overlapping variables playing out in global politics — the public health crisis that COVID-19 has spawned, the ongoing great power succession politics, and the debate on the essence of “China in Africa.” Without doubting the individual and collective capability of Nigerians to discern how the world works, the current burst of discontent against China is best understood as a manifestation of the fragility of China’s image in the Nigerian political community rather than a nationalist assertion. In other words, China’s hegemony or soft power or “charm offensive” is experiencing a reversal in its impact on popular consciousness in Nigeria. What is thus at stake here is the paradox about hegemony: its inherent vulnerability to counter-narratives even as it is the most effective form of power. The paradox is complicated in this case by the great power competition and the associated representational practice of power. The imagining and representation of “China in Africa” as a bogeyman, to an extent the world has not seen since the end of the Cold War, is specifically playing the counter-narrative against China. Led by the United States, this framing of China, especially of “China in Africa,” has sedimented in the public sphere over the years. Now, the idea is producing the reality it invokes – China as a predatory, amoral intruder. The resultant weakening explains China’s current vulnerability to discontent in Nigeria.

A Rising Hegemon and the Beaten Track

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

However, as much progress as China was making in presenting itself as without colonial stain in Africa, with her message of “win-win” development as well as being the acknowledged force for the boom in commodity trading from which the “Africa Rising” narrative sprouted, a number of negative sentiments were also piling up. And these sentiments echoed the framing of China as a neocolonial intruder through the image of Chinese political leaders as hard headed realists on a mission to plunder the continent; the well circulated notion of Chinese manufacturers, especially pharmaceutical companies, colluding with unscrupulous Nigerian traders to produce cheap but inferior products; the representation of the remarkable Chinese presence in the Nigerian textile, electronics, and footwear markets as evidence of what is to come; and narratives of unique Chinese racial practices.

These anti-China feelings were piling up in spite of the fact that, from 2001-2012, China’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in sub-Saharan Africa grew by 53 percent annually (compared to 16 percent annual growth for the EU, 29 percent for Japan and just 14 percent in the case of the United States). By 2012, Chinese FDI had risen from about $27 billion around 2001 to about $133 billion. As early as 2009, writers such as Deborah Brautigam were already asserting that, as far as large-scale private sector manufacturing was concerned, scant Western involvement in Africa had left China the lone, dominant actor. These must have been the facts behind global media framing of the 2014 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit largely as a catch-up game. Not only was the United States low on FDI by then, it was not competitive in infrastructure provisioning at any level comparable to the Chinese across Africa.

What should, therefore, become clear is how the current anti-China uproar is not necessarily located in the facts of the matter but in what those facts have been mobilized to prove or disprove. In other words, the current uproar is coming from the generation and sedimentation of specific ideas, concepts, phrases, and metaphors about China, mostly as a predatory intruder that should be suspected and feared rather than trusted. This is what discourse analysts call the language game – the use of words and the power that comes from that. At issue here is not the ethical or normative propriety of the language game, but how the use of words translates to power through the meaning that words infuse into on a reality, making language and reality one and the same thing. Below is how the language game worked against China’s “charm offensive” in Nigeria.

Framing “China in Africa”

Central to the story of Africa in the post-Cold War is the convergence of global powers on the continent, what University of North Carolina’s Margaret Lee has framed as 21st century scramble for Africa. The United States, China, the EU, Russia, Japan, India, Iran, Brazil, Turkey, South Korea, and France are all involved in this. But it is China’s involvement that has been variously problematized and even securitized. Although Johnnie Carson, U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs under the Obama administration, did not inaugurate the bogeyman narrative, he took it far when he told oil executives in Nigeria in early 2010, for example, how aggressive and pernicious a competitor China is. His message — that China is not in Africa for anything altruistic but primarily for China — was well targeted because oil executives constitute a small but powerful belt through which to spread such a message. Obviously, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton built on this during a 2012 visit to Zambia where she framed “China in Africa” as “new colonialism” and a threat to good governance in relation to liberal democracy, labor standards, the environment, and human rights regime.

It did not take long before Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, the then governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, wrote an op-ed articulating a position that shared a lot with Carson and Clinton’s. In arguing that “China in Africa” had a whiff of colonialism, Lamido was, consciously or otherwise, popularizing the American position beyond the oil and elite banking circle, positioning China as a threat. Given Lamido’s popularity across social, ideological, and regional tendencies in Nigeria, now and then, his intervention could not have been without advantages to China critics.

The U.S. framing of China reached its climax by 2014 when President Barack Obama staged the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit in Washington. That was where he differentiated the United States from China, portraying the U.S. as “a good partner, an equal partner, and a partner for the long term in Africa,” one interested in Africa not “simply for its natural resources; we recognize Africa for its greatest resource, which is its people and its talents and their potential.” Although he did not name China in this address to the Business Forum, his references to the United States in the same message as the responsible and genuine partner on the one hand and to some others as partners that took away Africa’s natural resources achieved that comparison. In any case, Senator Chris Coons completed the job of naming names by directly contrasting the two. In doing so, he privileged what he called the United States’ “values-driven policy and investments in people, especially in public health” to what he considered to be China’s “reputation for paying for the friendship of African governments with low-interest financing of construction projects.”

So, while China is generally regarded as a success story in the language game, probably in accordance with the challenge of “laying the basis for an alternative international system in the 21st century,” the United States plays the game from the position of an established or status quo power. Even as many variables are changing in global power politics, the United States and the Western world still hold the ace in terms of the language game in any audience.

U.S. influence is intact in many spheres in Nigeria. The universities are filled with scholars who trained in Western spaces of scholarship — more than in China, at the moment. The English language is an independent force, with particular reference to the influence of popular culture in general and the mass media in particular. As influential as the Hausa Language Service of China Radio International (CRI) is in northern Nigeria, for instance, it has not supplanted the VOA, the BBC, or Radio Deutschevelle. A similar claim can be made about the China Global Television Network (CGTV) in relation to CNN or BBC World, whose real competitor in Nigeria must be just Al Jazeera. The longer cultural interaction between Nigeria and the West/United States has meant a level of fusion that enhances American discursive power in the country relative to China. The business arena in Nigeria is diversifying as quite a number of Nigerians are “looking towards the East,” but it is debatable if that has amounted to a game changer. The United States has a history of king making in Nigeria, from the political to the business and cultural. It is also still the established intelligence power in Nigeria.

Things have, indeed, been changing but not fast enough to wash away these age-old advantages in favor of the West or make a large chunk of Nigerian not echo U.S. feelings on most issues of the day, notwithstanding pervasive and authentic radical nationalist consciousness. China is paying for that in the current burst of anti-China feelings.

Enjoying this article? Click here to subscribe for full access. Just $5 a month.

Conclusion

The above sets the ground for understanding the current discontent with China in Nigeria as the paradox of hegemony. The paradox is how much of a power resource hegemony can be, even as it cannot be secured from counter-narratives that could overwhelm it. The challenge for China is not rushing to work harder on hegemony in Nigeria but taking note of the very nature of hegemony, especially in the context of great power politics.

But the fragility of hegemony means that there is a challenge for Nigeria and Nigerians to position themselves against their country being turned into a battleground for great power discursive warfare. That would be no less than a repeat of the unproductive U.S.-USSR scenario in the Cold War, or of how the sharing of the African pie underlined 20th century global conflicts. It would be the ultimate tragedy. To avoid that, Nigerians must master contingent interpretation of politics, away from entrenched, doctrinaire positions which would neither change the United States’ or China’s strategic orientations nor make them countries Nigeria can afford to ignore.

Adagbo Onoja, a former Nigerian Foreign Affairs Ministerial Aide, (1999- 2003), teaches Political Science at The Catholic University of Nigeria, Abuja. As an academic, he focuses on critical geopolitics, great power competition in Africa and Interpretivism.

Nigeria sees China as a steady partner and its largest lender

Aug 18, 2022

https://merics.org/en/nigeria-sees-china-steady-partner-and-its-largest-lender?

You are reading chapter 6 of the MERICS Paper on China "Beyond blocs: global views on China and US-China relations". Click here to go to the table of contents.

Nigeria has the largest population and biggest economy in Africa, yet, it is confronted with serious challenges.1 About 80 million of Nigeria’s 200+ million people live in poverty. There is insufficient infrastructure, weak and ineffective institutions, transparency and governance issues, and an oil-dependent rent-seeking economy. Meanwhile, insurgency in the northeast is now being compounded by separatist Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) attacks in the southeast.2 Within that context, Nigeria-China relations are dominated by economic considerations. China is a major investor and an alternative to other sources of development finance like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and other bilateral lenders; it has become Nigeria’s largest bilateral lender.

Status quo: Economic relations are at the core

China is one of Nigeria’s top trading partners. According to the World Bank, Nigeria-China trade in products increased from about USD 1.2 billion in 2003 to USD 13.7 billion in 2019. Nigeria’s trade with the United States in the same period declined from USD 11.5 billion to USD 7.5 billion. Within the same period, Chinese investment in Nigeria increased from USD 24.4 million to 123.27 million. Nigeria became one of the top five Chinese investment destinations in Africa – after Kenya, The Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, and Ethiopia in 2020.3

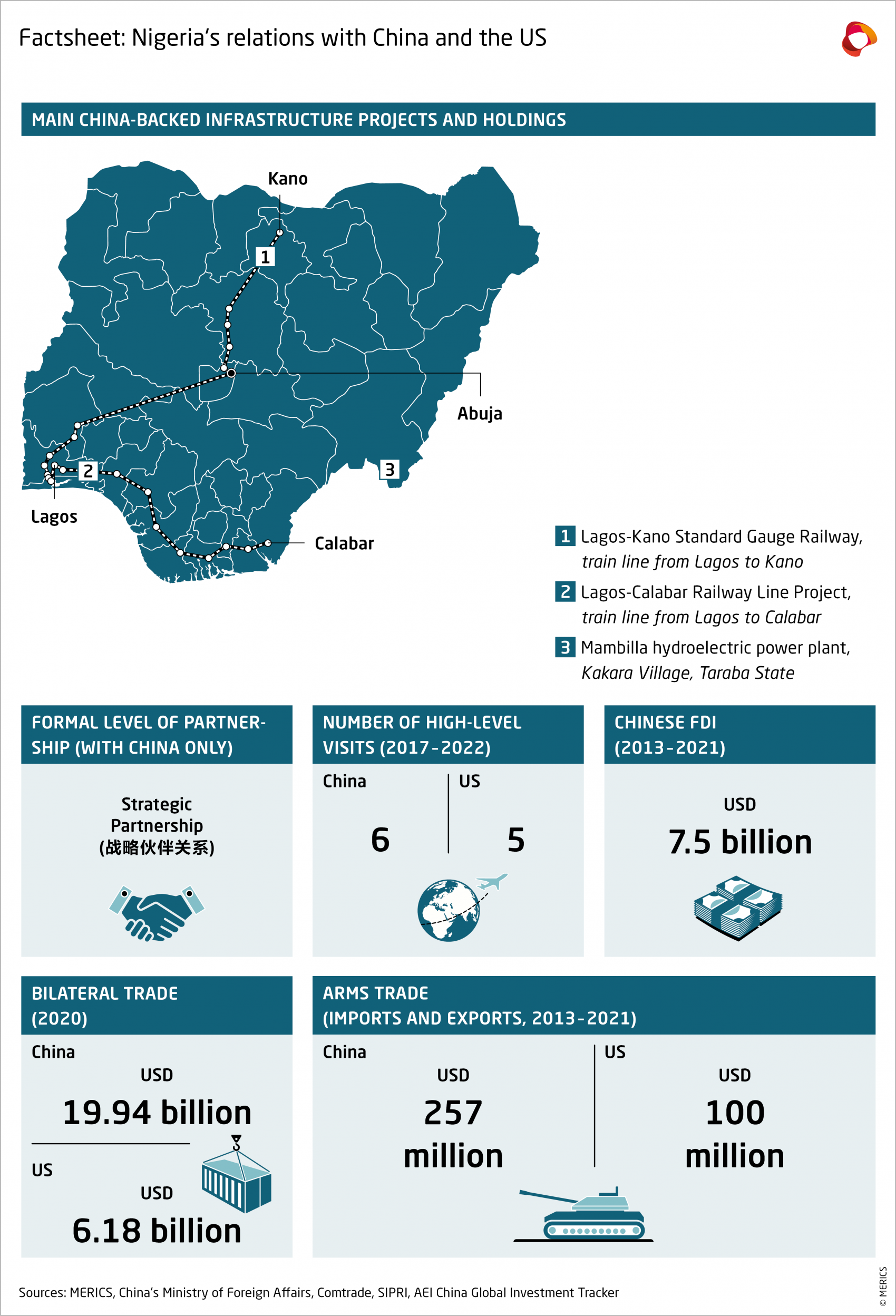

Beyond trade and investment, China is financing large projects and its companies are contracted to deliver their construction – including railways, road projects and the rehabilitation of Nigeria’s main four airports in Abuja, Lagos, Kano and Port Harcourt. All this makes China fundamental to Nigeria’s development finance. In addition to these projects, China has sold millions of USD worth of tanks and artillery to the Nigerian military.4

China’s rising influence in Nigeria, nonetheless, raises three main concerns worth stressing:

The first revolves around the opacity of China’s loans and infrastructure contracts, something that can encourage corruption and other illiberal activities. This opacity led Nigeria’s House of Representatives (i.e., the Lower House of the National Assembly) in May 2020 to decide unanimously to probe Chinese loans.5 They voted for the probe despite a plea from the Minister of Transportation, Rotimi Amaechi, that the inquiry might frustrate future Chinese loans.6 However, by late June 2021, there were media reports that the House probe was not proceeding.7

China’s response to the House’s probe was to emphasize that loans to Nigeria were mutually beneficial.8 Some months later, in February 2022, a two-man Chinese delegation, Wu Baocai and Li Ineijian, visited the national secretariat of the main opposition party, PDP, whose members in the House had moved and supported the motion for the probe, at its headquarters.9 Less than a month later, Wu led another Chinese delegation to the Inter-Party Advisory Council (IPAC), an umbrella body for all the registered political parties in Nigeria. These visits appear to have been successful as positive statements about China’s activities in the country were made by Iyorchia Ayu, the chairperson of the PDP, and by his IPAC counterpart, Yabagi Sani.10 By showing willingness to reach out to the main opposition party, the Chinese initiative may have laid a useful foundation if the 2023 general election brings a change of government.

Second, there are concerns that imports of Chinese products, especially textiles, are contributing to the demise of local industries. There have been protests amid reports linking Chinese textiles to the unemployment of thousands of Nigerians in the textile industry.

The third concern centers on Nigeria’s growing dependence on China. There have been situations where Nigeria has had to jostle to find alternative sources of finance when China – or Chinese banks – declined to fund projects they had initially committed to. Recently, the China Exim Bank declined to proceed with the funding of projects. The Nigerian government was forced to approach Standard Chartered to bridge the gap after China Exim Bank disbursed only USD 1.3 billion of an estimated total loan of USD 8.3 billion for the Lagos-Kano railway – a major infrastructure project to link Nigeria’s former capital and commercial center to its largest northern city.11

Geopolitics, China, and the United States: Nigeria searches for the best pragmatic deals

Like China, the United States occupies an important position in Nigeria’s economic, political and security relations. So far, US-China rivalry has had only a minimal impact on Nigeria. However, there could be a drastic impact if the rivalry persists and deepens. For instance, Nigeria’s telecommunications industry is increasingly dominated by Chinese technology firms led by Huawei, a multinational equipment and service provider with credit lines from state-owned Chinese banks.12

Thus, if the so-called ‘splinternet’ emerges – with Chinese and US technologies supporting different digital and internet ecosystems – it could have a disruptive impact and could force Nigeria(ns) to take sides. Not only have Chinese companies (e.g., Huawei and ZTE) dominated the telecommunications market by supplying the main service providers like MTN but also, like many African countries, Chinese-made smart phones have become popular in Nigeria.13 Meanwhile, the enormity of the internet split could have unintended implications and disruptions for the emerging fintechs in the West African country. It is important to mention that of the five fintech unicorns (i.e., start-ups worth over USD 1 billion) in Africa, three – “Interswitch, Flutterwave and Paystack – are Nigerian companies”.14

Thus far, Nigerian governments have managed their relationships with the US and China in a strongly pragmatic way. As Foreign Minister Geoffrey Onyeama put it during US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s 2021 Africa trip, “It’s not a question of one country or the other per se; it’s really a question of the best deal that we can strike.”15

Nigeria had a democratic transition of power in 2015, after the ruling Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) lost to the All Progressive Congress (APC). The next general election is due in early 2023 and will take place at a critical moment in the country’s history because, aside from the many security challenges, the country is confronted with socio-economic challenges. For instance, the outbreak of Covid-19 compounds the afore-mentioned pre-Covid poverty situation. Public universities have been on strike and their students have been at home for months. Given the level of frustration with the current government, there is a real chance for the opposition to return to power – although the current President, Muhammadu Buhari, will not be on the ballot. Instead, a former Governor of Lagos, Bola Ahmed Tinubu of the APC will be contesting against PDP’s Atiku Abubakar, a former Vice President, for the top job.

Although its relationship with China is important and strong, Nigeria’s political system and political affinities are more in tune with that of the US and Western Europe. Local media, civil society and successive governments offer a space where US and EU interests have operated without Chinese interference.

Perceptions: China is seen as a partner despite ups and downs

Public perceptions of China in Nigeria are generally positive.16 Afrobarometer polls in 2020 reported that 62 percent of Nigerians viewed China as a positive influence on their country – the same percentage as rated the United States positively.17 The trend continued in 2021, when 63 percent of Nigerians considered China’s political and economic influence as positive and gave the United States the same 63 percent score.18 At the elite level, China is considered a partner and seen as an alternative to traditional sources of development finance.

Top level political office holders in Nigeria and China have periodically exchanged visits. For instance, President Jiang Zemin and President Hu Jintao visited Nigeria in 2002 and 2006, respectively, after President Olusegun Obasanjo visited China in 1999 and 2005. President Umaru Yar’ Adua (in 2008), President Goodluck Jonathan (in 2013), and the sitting President, Buhari (in 2016) visited China.19 In addition to China’s Premier Li Keqiang’s visit to Nigeria in 2014, Chinese foreign ministers like Yang Jiechi (in 2010, and as President Xi Jinping’s special envoy in 2019), and Wang Yi (in 2017 and 2021) have visited Nigeria.

Anti-Chinese sentiment has occasionally flared up after, triggered by the maltreatment of Nigerians in Guangzhou in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic or the periodic maltreatment of locals by some Chinese companies in Nigeria.20 But these episodes have gradually faded, and the usual friendly relations returned. Of the 34 African countries, Nigerian ranked seventh highest in rating the Chinese development model best for their country in the 2019/2021 Afrobarometer survey. It was favored by 29 percent of respondents, though 36 percent favored the US model.21

However, there are controversial issues amid these broadly positive views of China. The decimation of the local textile industry is a focus of anti-China feelings, although government policies on textiles and other local factors have contributed to that industry’s decline as well. Thousands have protested against Chinese textile imports.22

The Nigeria-China relationship has gone through occasional sharp swings and instabilities over economic matters. When the government of President Olusegun Obasanjo initiated the short-lived oil-for-infrastructure policy with China in 2006, seeking to pay for Chinese infrastructure with oil, it was cancelled after only a few months by his hand-picked successor who was also from the PDP. Another example of instability in the economic relationship was China Exim Bank’s reluctance to proceed with funding the Lagos-Kano railway project.23 Although Nigeria’s ruling elites generally consider China a reliable alternative source of development finance, this perception, too, is susceptible to oscillations.

Outlook: A cautious China remains an attractive alternative

China has become a reliable major player in Nigeria’s infrastructure development over the last 20 years. However, the future relationship will need to weather increasing regional instability and push back against Chinese debt. Nigeria’s oil-rich economy is rent-seeking and has relied on exports of raw crude for years, though China is not a major market for Nigeria’s oil. More seriously, the impending global shift to renewable energy could devastate the economy.

Meanwhile, Nigeria is moving into an election period that will culminate in general elections in early 2023. The elections will likely take place amid escalating regional frictions. There is ongoing conflict in the northeast; simmering tensions in the southeast where there is a secessionist group and a call for an Ibo presidency; and persistent frictions in the southwest, where herdsmen attacks on local communities have generated fresh local nationalism that led to the first region-based security outfit, Amotekun, by the southwest governments in 2020 and attacks on a Fulani community in Oyo, a southwest state, by a pro-Yoruba Nation secessionist group led by Sunday “Igboho” Adeyemo in 2021. China appears to be pulling the breaks on some projects.24 Although this hesitancy could be tied to uncertainty in an election year, the question of Chinese loans to Nigeria becoming unsustainable is an issue.

Chinese development finance has led to a rise in debt. According to the Nigerian Debt Management Office, Chinese loans to Nigeria stood at about 10 percent (USD 3.3 billion) of the total external debt (USD 33.3 billion) at end-December 2020.25 While this appears manageable in terms of the total external debt portfolio, China is Nigeria’s top bilateral lender with 80 percent of the bilateral loans – which includes loans from France (USD 494 million), Germany (USD 184 million), Japan (USD 80 million), and India (USD 37 million). Thus, the narrative of a Chinese debt trap used by Western diplomats may soon find its way into national discourse. In 2020, questions about Chinese loans affecting Nigeria’s sovereignty became a major issue in the National Assembly and in the news.26

Although China has not become an election issue in Nigeria (as it did in Zambia’s 2006 national election), political elites have a tendency to criticize its conduct, especially when in opposition. The most frequent criticisms focus on growing Chinese loans to the government; the lack of transparency in such loan agreements; and the number of Chinese citizens working on China-funded construction projects. A cautious China may therefore be responding to local realities so as to reposition itself for all possible election outcomes.

In conclusion, Nigeria-China trade has increased in the last 20 years but in China’s favor. Although the voices of local stakeholders will become louder, the trade imbalance in favor of China will continue – at least until Nigeria’s government creates the necessary environment for local manufacturing to reverse the current situation. However, non-state actors like the media and civil society groups will remain critical elements in Nigeria-China relations. They are able to push back at the illiberal influence of Beijing and of Chinese companies where the Nigerian state fails.

The impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict: Security relations with China could deepen

Nigeria’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has mainly been to organize the evacuation of its stranded citizens in Ukraine and support the March 2022 UN resolution condemning the invasion. Nigeria’s relations with Russia are cordial (it has been a longstanding alternative source of military support ever since the 1960s Biafra War), the conflict in Ukraine could deepen Nigeria’s security relations with China, in the wake of Western sanctions on Russia.

As Nigeria’s struggles with escalating banditry and the conflicts with Boko Haram and Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), its reliance on Chinese military products will increase in the short and medium term. Western reluctance to sell weapons to the Nigerian government will play a role.

Rumors that Russian hackers were targeting Nigerian websites following the invasion increased anti-Russia commentaries online and in the media and could complicate this shift. There is no indication that China’s response to the invasion, specifically its reluctance to criticize Russia, will affect Nigeria-China relations.