来自维基百科,自由百科全书

“中国世纪”是一个新词,指21世纪可能在地缘经济或地缘政治上由中华人民共和国主导,[1]类似于“美国世纪”指20世纪,“英国世纪”指19世纪。[2][3] 该词组尤其用于指代中国经济可能超越美国成为世界最大经济体的观点。[4][5] 与之类似的还有“中国崛起”(简体中文:中国崛起;繁体中文:中國崛起;拼音:Zhōngguó juéqǐ)。[6][7]

中国发起了“一带一路”倡议。据分析人士称,这是一项地缘战略努力,旨在在全球事务中发挥更大作用,并挑战美国战后的霸权。[8][9][10]也有观点认为,中国共同创立亚洲基础设施投资银行和新开发银行,是为了在发展融资方面与世界银行和国际货币基金组织竞争。[11][12] 2015年,中国启动了“中国制造2025”战略规划,以进一步发展制造业。关于这些规划在提升中国全球地位方面的有效性和实用性,一直存在争议。

中国崛起为全球经济强国与其庞大的劳动人口息息相关。[13] 然而,中国人口老龄化速度比历史上几乎任何其他国家都快。[13][14] 当前的人口趋势可能会阻碍经济增长,造成具有挑战性的社会问题,并限制中国成为新的全球霸主的能力。[13][15][16][17] 中国主要依靠债务驱动的经济增长也引发了人们对巨大信贷违约风险和潜在金融危机的担忧。

据《经济学人》报道,按购买力平价(PPP)计算,中国经济在2013年已成为世界最大经济体。[18] 以汇率计算,2020年和2021年初的一些预测认为,中国可能在2028年超过美国,[19] 如果人民币进一步走强,则可能在2026年超过美国。[20] 截至2021年7月,彭博分析师估计,中国要么在2030年代超过美国成为世界最大经济体,要么永远无法实现这一目标。[21] 一些学者认为,中国的崛起已经达到顶峰,随后可能出现停滞或衰退。[22][23][24]

争论与因素

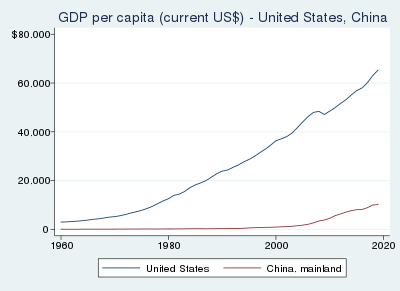

GDP(现价美元,未根据购买力平价调整)- 美国、中国(单位:万亿美元,1960-2019)

人均名义GDP(未根据购买力平价调整)- 美国、中国(1960-2019)

另请参阅:一带一路倡议、中国制造2025和区域全面经济伙伴关系

据估计,中国经济在16、17和18世纪初是世界最大经济体。[25] 约瑟夫·斯蒂格利茨曾表示,“中国世纪”始于2014年。[26] 《经济学人》援引中国自2013年以来的GDP数据(按购买力平价计算),认为“中国世纪正在顺利开启”。[27]

自 2013 年起,中国发起了“一带一路”倡议,未来投资额接近 1 万亿美元[28]。分析人士认为,此举是中国在全球事务中发挥更大作用的地缘战略推动力。[8][9] 也有人认为,中国共同创立了亚洲基础设施投资银行和新开发银行,是为了在发展融资方面与世界银行和国际货币基金组织竞争。[11][12] 2015 年,中国启动了“中国制造 2025”战略规划,以进一步发展制造业,旨在提升中国工业的制造能力,从劳动密集型工厂发展成为技术密集型强国。

2020 年 11 月,中国签署了区域全面经济伙伴关系协定,作为一项自由贸易协定[29][30][31],以对抗跨太平洋伙伴关系协定[32][33][34]。一些评论人士认为该协议是中国的“巨大胜利”,[35][36]尽管事实证明,如果没有印度的参与,该协议只会使中国2030年的GDP增长0.08%。[37][38]

布鲁金斯学会外交政策高级研究员瑞安·哈斯表示,中国“势不可挡,即将超越步履蹒跚的美国”的论调,很大程度上是由中国官方媒体所宣传的。他还补充道:“威权体制善于展示自身优势,掩盖自身劣势。”[39] 政治学家马修·克罗尼格表示:“‘一带一路’倡议和‘中国制造2025’这两个经常被引用为中国高瞻远瞩的计划,实际上都是习近平分别在2013年和2015年才宣布的。这两个计划都太新了,不足以称之为成功的长期战略规划的杰出典范。”[40]

据加州大学圣地亚哥分校教授兼中国问题专家巴里·诺顿称,2016年,中国城镇家庭的平均收入为42,359元人民币,城镇居民平均收入为16,02元人民币。

2019年,中国农村家庭人均收入排名第一。即使按购买力平价换算,中国城镇居民平均收入也略高于1万美元,农村居民平均收入略低于4000美元。诺顿质疑,像这样一个中等收入国家,在开拓新技术方面“投入如此不成比例的风险支出”是否合理。他评论说,虽然从纯粹的经济角度来看这没有道理,但中国政策制定者在实施“中国制造2025”等产业政策时,还有“其他考虑”。[41]

根据不同的情景假设,据估计,中国要么在2030年代超越美国成为世界最大经济体,要么永远无法做到这一点。[21]

国际关系

2023年军费开支排名前五的国家[42]

2011年,时任哈佛大学肯尼迪学院研究员的迈克尔·贝克利发表了其著作《中国的世纪?为何美国的优势将持续》。该书驳斥了美国相对于中国正在衰落的观点,也否认了美国为维持全球化体系而承担的霸权负担导致了其衰落。贝克利认为,美国的实力是持久的,“单极”和全球化是主要原因。他指出:“美国从其优势地位中获得了竞争优势,而全球化使其能够利用这些优势,吸引经济活动,并操纵国际体系使其受益。”[43]

贝克利认为,如果美国陷入终极衰落,它就会采取新重商主义的经济政策,并放弃在亚洲的军事承诺。 “然而,如果美国并未衰落,而全球化和霸权是主要原因,那么美国就应该反其道而行之:通过维持自由的国际经济政策来遏制中国的增长,并通过在亚洲维持强大的政治和军事存在来抑制中国的野心。”[43] 贝克利认为,美国受益于现存的霸权地位——1990年,美国并没有为了自身利益而颠覆国际秩序,而是现有秩序在其周围崩溃了。

对美国能否保持领先地位持怀疑态度的学者包括罗伯特·佩普,他计算得出,“现代历史上最大的相对衰落之一”源于“技术向世界其他地区的传播”。[44]同样,费雷德·扎卡里亚写道:“过去二十年的单极秩序正在衰落,并非因为伊拉克战争,而是因为全球权力的广泛扩散。”[45] 保罗·基普楚姆巴在《21世纪的中国与非洲:战略探索》一书中预测,21世纪中美之间将爆发一场致命的冷战;如果这场冷战不发生,他预测中国将在全球霸权的各个方面取代美国。[46]

学者罗斯玛丽·富特写道,中国的崛起引发了美国在亚太地区霸权的一些重新谈判,但中国公开宣称的雄心与政策行动之间的不一致引发了各种形式的抵制,使得美国的霸权仅受到部分挑战。[47]与此同时,C·拉贾·莫汉观察到,“中国的许多邻国正稳步走向要么在北京和华盛顿之间保持中立,要么干脆接受被其庞大邻国主导”。然而,他也指出,澳大利亚、印度和日本已准备好挑战北京。[48] 理查德·海德里安认为,“美国相对于中国的优势在于其广泛且出人意料地持久的区域联盟网络,尤其是与中等强国日本、澳大利亚以及日益壮大的印度的联盟。这些国家对中国日益增强的自信有着共同的担忧,尽管这种担忧并非完全相同。”[49]

在全球担忧中国的经济影响力包含政治影响力之际,中国领导人习近平表示:“中国无论发展到什么程度,都永远不称霸”。[50] 在多次国际峰会上,其中包括2021年1月的世界经济论坛,中国领导人习近平表示倾向于多边主义和国际合作。[51] 然而,政治学家斯蒂芬·沃尔特将这一公开信息与中国对邻国的恐吓进行了对比。斯蒂芬·沃尔特建议,美国“应该采纳习近平提出的多边合作倾向,并利用美国庞大的盟友和伙伴,在各种多边论坛中寻求有利结果”。尽管他鼓励互利合作的可能性,但他也认为,“两个最大强国之间的竞争在很大程度上根植于新兴的国际体系结构中”。[51] 新加坡前总理李光耀认为,中国“最初”希望与美国平等共存本世纪,但“有意成为”

最终成为世界上最强大的国家”。[49]

余雷和隋菲娅在《亚欧期刊》上撰文指出,中俄战略伙伴关系“表明了中国增强‘硬’实力以提升其在系统(全球)层面地位的战略意图”。[52]

2018年,陈向明撰文指出,中国可能正在创造一场新的大博弈,与最初的大博弈相比,这场博弈转向了地缘经济竞争。陈向明指出,中国将扮演大英帝国的角色(俄罗斯将扮演19世纪俄罗斯帝国的角色),就像“主导力量对抗较弱的独立中亚国家”。此外,他还指出,“一带一路”倡议最终可能将“中国与中亚的关系转变为一种附庸关系,其特点是中国为维护边境安全和政治稳定而进行跨境投资”。[53]

快速老龄化和人口挑战

历史人口估计值与预测人口根据联合国针对当前人口最多的三个国家(印度、中国和美国)的中等变量情景,预测中国到2100年将达到的人口老龄化水平。

世界银行对中国2050年劳动年龄人口的预测

另见:中国老龄化

中国崛起为全球经济强国,与其庞大的劳动人口息息相关。[13] 然而,中国人口老龄化的速度几乎超过了历史上任何其他国家。[13][14] 根据预测,到2050年,中国超过退休年龄的人口比例将达到总人口的39%。中国在发展早期就迅速老龄化,其速度比其他国家都要快。[13] 当前的人口趋势可能会阻碍经济增长,引发具有挑战性的社会问题,并限制中国成为新的全球霸权的能力。[13][15][16][17]

地缘政治情报服务局客座专家布伦丹·奥莱利写道:“人口下降引发经济危机、政治不稳定、移民和生育率进一步下降的负反馈循环的黑暗情景对中国??来说是非常现实的”。[54][55]美国企业研究所的经济学家和人口专家尼古拉斯·埃伯施塔特表示,当前的人口趋势将压倒中国的经济和地缘政治,使其崛起更加不确定。他说:“经济英雄式增长的时代已经结束。”[56]

布鲁金斯学会的瑞安·哈斯表示,中国的“劳动年龄人口已在减少;到2050年,中国每8名劳动者对应1名退休人员,将减少到2名劳动者对应1名退休人员。此外,随着人口受教育程度提高、城镇化程度提高以及采用技术提高制造业效率,中国已经挤占了大部分生产力的大幅增长。”[39]

美国经济学家斯科特·罗泽尔和研究员娜塔莉·赫尔认为:“中国看起来更像20世纪80年代的墨西哥或土耳其,而不是20世纪80年代的台湾或韩国。没有哪个国家在高中教育普及率低于50%的情况下能够跻身高收入国家。鉴于中国高中教育普及率仅为30%,该国可能面临严重困境。”他们警告称,由于城乡教育差距和结构性失业,中国有可能陷入中等收入陷阱。[57][58]彼得森国际经济研究所的经济学家马丁·乔泽姆帕和黄天雷对此表示赞同,并补充道:“中国长期以来忽视了农村发展”,必须投资于农村社区的教育和卫生资源,以解决持续的人力资本危机。[58]

经济增长与债务

中国在全球出口中的份额(1990-2019)

在2020年新冠疫情期间,中华人民共和国是唯一一个实现增长的主要经济体。[59] 中国经济增长了2.3%,而美国经济和欧元区预计分别萎缩3.6%和7.4%。2020年,中国在全球GDP中的份额上升至16.8%,而美国经济占全球GDP的22.2%。[60]然而,根据国际货币基金组织2021年全球经济展望报告,到2024年底,中国经济规模预计将低于此前预测,而美国经济规模预计将高于此前预测。[61]

中国增加贷款的主要动力来自其希望尽快提高经济增长率。几十年来,地方政府官员的政绩几乎完全取决于其促进经济增长的能力。Amanda Lee在《南华早报》上报道称:“随着中国经济增长放缓,人们越来越担心其中许多债务面临违约风险,这可能引发中国国家主导的金融体系的系统性危机。”[62]

Enodo Economics的Diana Choyleva预测,中国的债务比率将很快超过日本危机高峰时期的水平。[63] Choyleva认为:“有证据表明,北京意识到自己正深陷债务泥潭,

需要救生圈,只要看看政府自己的行动就知道了。它终于在公司债券市场注入了一定程度的定价纪律,并积极鼓励外国投资者为减少巨额坏账提供资金。”[63]

中国的债务占GDP的比率从2010年第一季度的178%上升到2020年第一季度的275%。[63] 2020年第二季度和第三季度,中国的债务占GDP的比率接近335%。[62] 布鲁金斯学会的瑞安·哈斯表示:“中国在基础设施投资方面的生产性空间正在耗尽,不断上升的债务水平将进一步使其增长路径复杂化。”[39]

中国政府定期修订其GDP数据,通常是在年底。由于地方政府面临着实现预设增长目标的政治压力,许多人对统计数据的准确性表示怀疑。[64] 据芝加哥大学布斯商学院经济学家谢长泰称,中国大学经济学教授宋正香港及其合著者认为,2008年至2016年间,中国经济增长率可能每年被高估1.7%,这意味着政府可能在2016年高估了中国经济规模12%至16%。[65][66]

美国战略家兼历史学家爱德华·勒特韦克认为,中国不会面临巨大的经济或人口问题,但会在战略上失败,因为“皇帝做所有的决定,却没有人可以纠正他”。他表示,从地缘政治角度来看,中国在2020年凭借极权政府的措施“赢得了一年的竞争优势”,但这也使“中国威胁”凸显出来,迫使其他国家政府做出回应。[67]

社会学家孔诰烽指出,尽管中国在新冠疫情期间的大量放贷使经济在最初的封锁后迅速反弹,但也加剧了许多国家本已深厚的债务负担。中国企业,到2021年经济增长将放缓,并抑制长期表现。洪教授还指出,尽管2008年主要在宣传中声称人民币可能取代美元成为储备货币,但十年后,人民币在国际使用中却停滞不前,甚至下降,排名低于英镑,更不用说美元了。[68]

中国衰落

一些学者认为,中国的崛起将在2020年代结束。外交政策专家迈克尔·贝克利和哈尔·布兰兹认为,由于“严重的资源匮乏”、“人口崩溃”以及“失去了使其发展壮大的欢迎世界”,中国作为一个修正主义大国,几乎没有时间改变世界现状,使其对自身有利,并补充说,“中国巅峰”已经到来。[22]

美国海军战争学院的安德鲁·埃里克森和贝克研究所的加布里埃尔·柯林斯认为,中国的实力正达到顶峰,“这个体系越来越意识到,它只有很短的时间来实现一些最关键、长期坚持的目标,这将带来十年的危险”。[23]《华盛顿邮报》专栏作家戴维·冯·德雷尔写道,西方应对中国的衰落将比应对中国的崛起更困难。[69]

卡托研究所的约翰·穆勒认为,中国“可能会出现衰退,或至少是长期的停滞,而不是持续崛起”。他列举了环境、腐败、民族和宗教紧张局势、中国对外资企业的敌意等因素,这些都是导致中国即将衰落的因素。[24]

威斯康星大学麦迪逊分校人口与健康研究员易福贤认为,“中国世纪”已经“结束”。

The Chinese Century

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Chinese Century is a neologism suggesting that the 21st century may be geoeconomically or geopolitically dominated by the People's Republic of China,[1] similar to how the "American Century" refers to the 20th century and the "British Century" to the 19th.[2][3] The phrase is used particularly in association with the idea that the economy of China may overtake the economy of the United States to be the largest in the world.[4][5] A similar term is China's rise or rise of China (simplified Chinese: 中国崛起; traditional Chinese: 中國崛起; pinyin: Zhōngguó juéqǐ).[6][7]

China created the Belt and Road Initiative, which according to analysts has been a geostrategic effort to take a larger role in global affairs and challenges American postwar hegemony.[8][9][10] It has also been argued that China co-founded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank to compete with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in development finance.[11][12] In 2015, China launched the Made in China 2025 strategic plan to further develop its manufacturing sector. There have been debates on the effectiveness and practicality of these programs in promoting China's global status.

China's emergence as a global economic power is tied to its large working population.[13] However, the population in China is aging faster than almost any other country in history.[13][14] Current demographic trends could hinder economic growth, create challenging social problems, and limit China's capabilities to act as a new global hegemon.[13][15][16][17] China's primarily debt-driven economic growth also creates concerns for substantial credit default risks and a potential financial crisis.

According to The Economist, on a purchasing-power-parity (PPP) basis, the Chinese economy became the world's largest in 2013.[18] On a foreign exchange rate basis, some estimates in 2020 and early 2021 have determined that China could overtake the U.S. in 2028,[19] or 2026 if the Chinese currency further strengthened.[20] As of July 2021, Bloomberg L.P. analysts estimated that China may either overtake the U.S. to become the world's biggest economy in the 2030s or never be able to reach such a goal.[21] Some scholars believe that China's rise has peaked and that an impending stagnation or decline may follow.[22][23][24]

Debates and factors

[edit]

See also: Belt and Road Initiative, Made in China 2025, and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

China's economy was estimated to be the largest in the 16th, 17th and early 18th century.[25] Joseph Stiglitz said the "Chinese Century" had begun in 2014.[26] The Economist has argued that "the Chinese Century is well under way", citing China's GDP since 2013, if calculated on a purchasing-power-parity basis.[27]From 2013, China created the Belt and Road Initiative, with future investments of almost $1 trillion[28] which according to analysts has been a geostrategic push for taking a larger role in global affairs.[8][9] It has also been argued that China co-founded the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank to compete with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in development finance.[11][12] In 2015, China launched the Made in China 2025 strategic plan to further develop the manufacturing sector, with the aim of upgrading the manufacturing capabilities of Chinese industries and growing from labor-intensive workshops into a more technology-intensive powerhouse.

In November 2020, China signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership as a free trade agreement[29][30][31] in counter to the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[32][33][34] The deal has been considered by some commentators as a "huge victory" for China,[35][36] although it has been shown that it would add just 0.08% to China's 2030 GDP without India's participation.[37][38]

Ryan Hass, a senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution, said that much of the narrative of China "inexorably rising and on the verge of overtaking a faltering United States" was promoted by China's state-affiliated media outlets, adding, "Authoritarian systems excel at showcasing their strengths and concealing their weaknesses."[39] Political scientist Matthew Kroenig said, "the plans often cited as evidence of China's farsighted vision, the Belt and Road Initiative and Made in China 2025, were announced by Xi only in 2013 and 2015, respectively. Both are way too recent to be celebrated as brilliant examples of successful, long-term strategic planning."[40]

According to Barry Naughton, a professor and China expert at the University of California, San Diego, the average income in China was CN¥42,359 for urban households and CN¥16,021 for rural households in 2019. Even at the purchasing power parity conversion rate, the average urban income was just over US$10,000 and the average rural income was just under US$4,000 in China. Naughton questioned whether it is sensible for a middle income country of this kind to be taking "such a disproportionate part of the risky expenditure involved in pioneering new technologies". He commented that while it does not make sense from a purely economic perspective, Chinese policymakers have "other considerations" when implementing their industrial policy such as Made in China 2025.[41]

Depending on different assumptions of scenarios, it has been estimated that China would either overtake the U.S. to become the world's biggest economy in the 2030s or never be able to do so.[21]

International relations

[edit]  |

| Top five countries by military expenditure in 2023.[42] |

Beckley believes that if the United States was in terminal decline, it would adopt neomercantilist economic policies and disengage from military commitments in Asia. "If however, the United States is not in decline, and if globalization and hegemony are the main reasons why, then the United States should do the opposite: it should contain China’s growth by maintaining a liberal international economic policy, and it should subdue China’s ambitions by sustaining a robust political and military presence in Asia."[43] Beckley believes that the United States benefits from being an extant hegemon—the U.S. did not overturn the international order to its benefit in 1990, but rather, the existing order collapsed around it.

Scholars that are skeptical of the U.S.'s ability to maintain a leading position include Robert Pape, who has calculated that "one of the largest relative declines in modern history" stems from "the spread of technology to the rest of the world".[44] Similarly, Fareed Zakaria writes, "The unipolar order of the last two decades is waning not because of Iraq but because of the broader diffusion of power across the world."[45] Paul Kipchumba in Africa in China's 21st Century: In Search of a Strategy predicts a deadly cold war between the U.S. and China in the 21st century, and, if that cold war does not occur, he predicts China will supplant the U.S. in all aspects of global hegemony.[46]

Academic Rosemary Foot writes that the rise of China has led to some renegotiations of the U.S. hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region, but inconsistency between China's stated ambitions and policy actions has prompted various forms of resistance which leaves U.S. hegemony only partially challenged.[47] Meanwhile, C. Raja Mohan observes that "many of China’s neighbors are steadily drifting toward either neutrality between Beijing and Washington or simply acceptance of being dominated by their giant neighbor." However, he also notes that Australia, India, and Japan have readily challenged Beijing.[48] Richard Heyderian proposes that "America’s edge over China is its broad and surprisingly durable network of regional alliances, particularly with middle powers Japan, Australia and, increasingly, India, which share common, though not identical, concerns over China’s rising assertiveness."[49]

In the midst of global concerns that China's economic influence included political leverage, Chinese leader Xi Jinping stated "No matter how far China develops, it will never seek hegemony".[50] At several international summits, one being the World Economic Forum in January 2021, Chinese leader Xi Jinping stated a preference for multilateralism and international cooperation.[51] However, political scientist Stephen Walt contrasts the public message with China's intimidation of neighboring countries. Stephen Walt suggests that the U.S. "should take Xi up on his stated preference for multilateral engagement and use America’s vastly larger array of allies and partners to pursue favorable outcomes within various multilateral forums." Though encouraging the possibility of mutually beneficial cooperation, he argues that "competition between the two largest powers is to a considerable extent hardwired into the emerging structure of the international system."[51] According to former Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, China will "[initially] want to share this century as co-equals with the U.S.", but have "the intention to be the greatest power in the world" eventually.[49]

Writing in the Asia Europe Journal, Lei Yu and Sophia Sui suggest that the China-Russia strategic partnership "shows China’s strategic intention of enhancing its 'hard' power in order to elevate its status at the systemic (global) level."[52]

In 2018, Xiangming Chen wrote that China was potentially creating a New Great Game, shifted to geoeconomic competition compared with the original Great Game. Chen stated that China would play the role of the British Empire (and Russia the role of the 19th century Russian Empire) in the analogy as the "dominant power players vs. the weaker independent Central Asian states". Additionally, he suggested that ultimately the Belt and Road Initiative could turn the "China-Central Asia nexus into a vassal relationship characterized by cross-border investment by China for border security and political stability."[53]

Rapid aging and demographic challenges

[edit]

See also: Aging of China

China's emergence as a global economic power is tied to its large, working population.[13] However, the population in China is aging faster than almost any other country in history.[13][14] In 2050, the proportion of Chinese over retirement age will become 39 percent of the total population according to projections. China is rapidly aging at an earlier stage of its development than other countries.[13] Current demographic trends could hinder economic growth, create challenging social problems, and limit China's capabilities to act as a new global hegemony.[13][15][16][17]Brendan O'Reilly, a guest expert at Geopolitical Intelligence Services, wrote, "A dark scenario of demographic decline sparking a negative feedback loop of economic crisis, political instability, emigration and further decreased fertility is very real for China".[54][55] Nicholas Eberstadt, an economist and demographic expert at the American Enterprise Institute, said that current demographic trends will overwhelm China's economy and geopolitics, making its rise much more uncertain. He said, "The age of heroic economic growth is over."[56]

Ryan Hass at the Brookings said that China's "working-age population is already shrinking; by 2050, China will go from having eight workers per retiree now to two workers per retiree. Moreover, it has already squeezed out most of the large productivity gains that come with a population becoming more educated and urban and adopting technologies to make manufacturing more efficient."[39]

According to American economist Scott Rozelle and researcher Natalie Hell, "China looks a lot more like 1980s Mexico or Turkey than 1980s Taiwan or South Korea. No country has ever made it to high-income status with high school attainment rates below 50 percent. With China's high school attainment rate of 30 percent, the country could be in grave trouble." They warn that China risks falling into the middle income trap due to the rural urban divide in education and structural unemployment.[57][58] Economists Martin Chorzempa and Tianlei Huang of the Peterson Institute agree with this assessment, adding that "China has overlooked rural development much too long", and must invest in the educational and health resources of its rural communities to solve an ongoing human capital crisis.[58]

Economic growth and debt

[edit]

China's increased lending has been primarily driven by its desire to increase economic growth as fast as possible. The performance of local government officials has for decades been evaluated almost entirely on their ability to produce economic growth. Amanda Lee reports in the South China Morning Post that "as China’s growth has slowed, there are growing concerns that many of these debts are at risk of default, which could trigger a systemic crisis in China’s state-dominated financial system".[62]

Diana Choyleva of Enodo Economics predicts that China's debt ratio will soon surpass that of Japan at the peak of its crisis.[63] Choyleva argues "For evidence that Beijing realizes it is drowning in debt and needs a lifebuoy, look no further than the government's own actions. It is finally injecting a degree of pricing discipline into the corporate bond market and it is actively encouraging foreign investors to help finance the reduction of a huge pile of bad debt."[63]

China's debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 178% in the first quarter of 2010 to 275% in the first quarter of 2020.[63] China's debt-to-GDP ratio approached 335% in the second and third quarters of 2020.[62] Ryan Hass at the Brookings said, "China is running out of productive places to invest in infrastructure, and rising debt levels will further complicate its growth path."[39]

The PRC government regularly revises its GDP figures, often toward the end of the year. Because local governments face political pressure to meet pre-set growth targets, many doubt the accuracy of the statistics.[64] According to Chang-Tai Hsieh, an economist at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, Michael Zheng Song, an economics professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and coauthors, China's economic growth may have been overstated by 1.7 percent each year between 2008 and 2016, meaning that the government may have been overstating the size of the Chinese economy by 12-16 percent in 2016.[65][66]

According to American strategist and historian Edward Luttwak, China will not be burdened by huge economic or population problems, but will fail strategically because "the emperor makes all the decisions and he doesn't have anybody to correct him." He said that geopolitically, China "gained one year in the race" in 2020 by using the measures of a totalitarian government, but this has brought the "China threat" to the fore, pushing other governments to respond.[67]

Sociologist Ho-Fung Hung stated that, although China's extensive lending during the COVID-19 pandemic allowed a quick rebound after the initial lockdown, it contributed to the already deep indebtedness of many of China's corporations, slowing the economy by 2021 and depressing long-term performance. Hung also pointed out that in 2008, although it was claimed mainly in propaganda that the Chinese yuan could overtake the US dollar as a reserve currency, after a decade the yuan has since stalled and decreased in international usage, ranking below the British pound sterling, let alone the dollar.[68]

Chinese decline

[edit]According to Andrew Erickson of the U.S. Naval War College and Gabriel Collins of the Baker Institute, China's power is peaking, creating "a decade of danger from a system that increasingly realizes it only has a short time to fulfill some of its most critical, long-held goals".[23] David Von Drehle, a columnist for The Washington Post, wrote that it would be more difficult for the West to manage China's decline than its rise.[69]

According to John Mueller at the Cato Institute, a "descent or at least prolonged stagnation might come about, rather than a continued rise" for China. He listed the environment, corruption, ethnic and religious tensions, Chinese hostility toward foreign businesses, among others, as contributing factors to China's impending decline.[24]

According to Yi Fuxian, a demography and health researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Chinese Century is "already over".[70]