《英脱欧公投随想之四》

相对经济规模

《华尔街日报》Brexit Will Put the U.S. Back Atop the World GDP Rankings(标题不无幸灾乐祸之意)

《英国卫报》

一大堆经济学大腕,通天的观点

(维基)欧盟经济和英国的相对成分

| 2015 | 总产值 | 人均总产值 | 比例 |

| 欧盟 | 14,625.40 | 28,700 | 100.0% |

| 德国 | 3,025.90 | 37,100 | 20.7% |

| 英国 | 2,568.90 | 39,500 | 17.6% |

| 法国 | 2,183.60 | 32,800 | 14.9% |

| 意大利 | 1,636.40 | 26,900 | 11.2% |

| 西班牙 | 1,081.20 | 23,300 | 7.4% |

| 荷兰 | 678.6 | 41,000 | 4.6% |

| 瑞典 | 444.2 | 45,300 | 3.0% |

| 波兰 | 427.7 | 11,100 | 2.9% |

| 比利时 | 409.4 | 36,500 | 2.8% |

| 奥地利 | 337.2 | 39,100 | 2.3% |

单位:欧元

贸易

英国贸易(英国广播公司)

Trade is important for Britain because about 28% of what we produce is sold abroad, exported

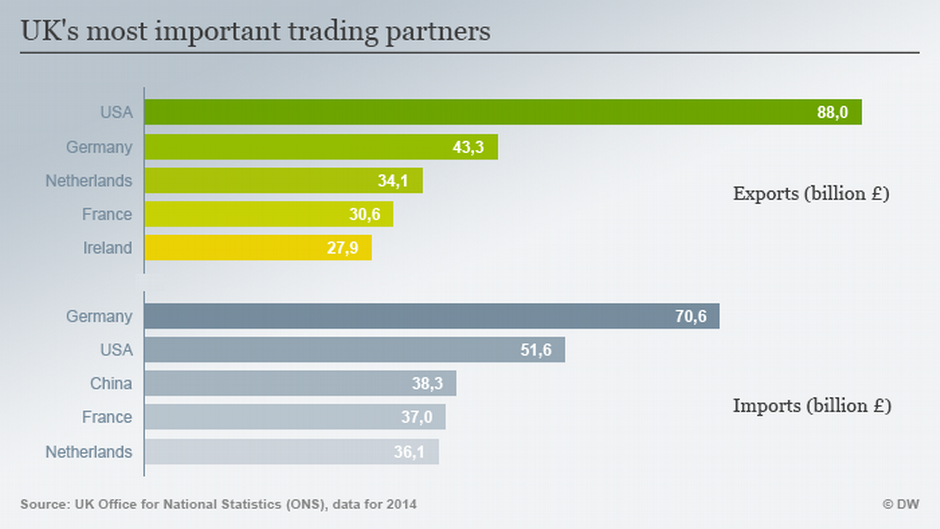

英国的主要贸易伙伴(德国之声)

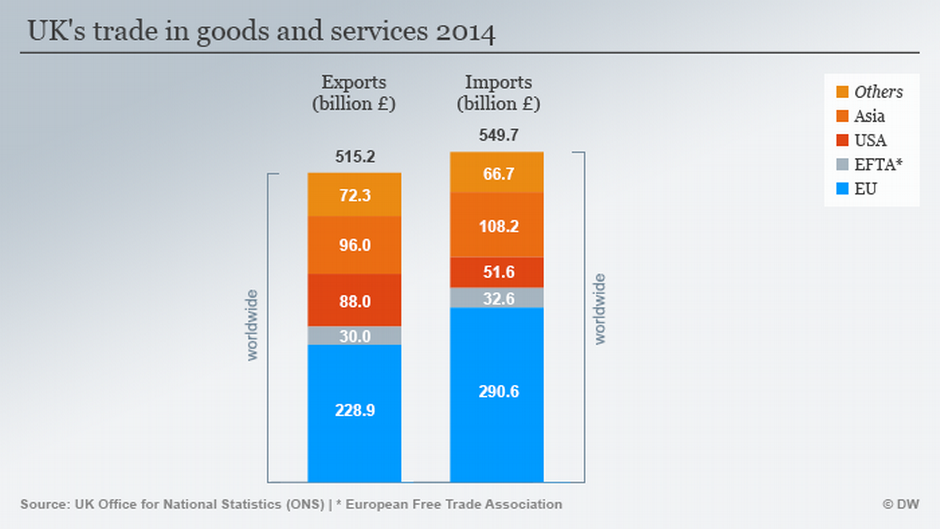

按产业:

按世界区域:

标普:

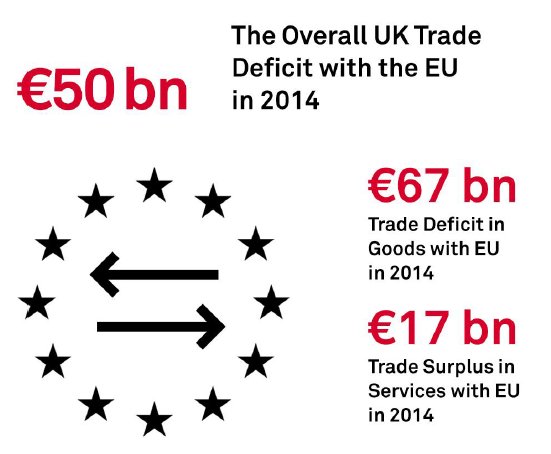

英国与欧盟间的贸易逆差,是英国的筹码,与德国间的逆差尤其大,这是为何德国口气最软的原因。

这也解释了为什么公投后的第二天德国股市比英国股市跌的多多了。

德国贸易数据:

注:德国出口很强,尽管不是世界贸易量最大的国家的几名,但总算差世界第一,比中国还高。

《经济学人杂志》是英国保守体制的捍卫人,英国和西方自由资本主义的倡导者,反对脱欧及其卖力。这是它旗下《商机智库Business Intelligence》主任外特(Alex White)的警告:

1. Brexit has plunged the UK into political, economic and market turmoil. We expect this turmoil to be sustained2. Financial market volatility will persist, while uncertainty over the future of the UK's relationship with EU will feed into real economy3. We significantly revised our economic fcast. After growth of 1.5% this year, we expect contraction of 1% in 20174. We expect to see decline in investment of 8% and decline in private consumption of 3% in 2017 with the pound levelling out at $1.245. The vote has transformed our fiscal forecasts. Falling tax rev & higher social transfers as unemployment rises6. We now expect the UK's public debt burden to reach 100% of GDP by 20187. This hit brings UK's post-crisis recovery to a halt. 2018 real GDP will be almost 4% below pre-referendum forecast (2020 = 6% below)8. While this is going on, politics will remain deeply fractious. The Govt, the main parties, parliament & the Union all face big threats9. We expect two months of chaos in the near-term. New PM Johnson (or May) will be in post in Sept, and start to figure out way ahead10. The UK will likely invoke Art 50 before year end, implying that negotiations will conclude in late 201811. UK will agree an EEA minus deal with significant constraints on services access in return for limitations on migration12. Much of the financial services sector may be left in the cold13. New PM will eat heroic quantities of humble pie to get the deal; UK will be permanently out of the room on big decisions14: This new deal will be confirmed through either a second referendum or a general election at the end of the process15. Leavers will tell voters they wont get what they want on migration. Will lead to major backlash = structural rise for radical right16. This is a particular threat for Labour. We expect UKIP etc to mount a serious challenge in Labour heartlands (even with Corbyn gone)17. UK establishment will take time to fully reassert itself. Lack of planning / credibility will lead to ongoing doubts about capacity18. Much of the UK's 'political stability premium' based on predictability / reliability etc could be lost for long time19. As UK leaves, recovery will be underway but economy & politics will look structurally different20. We are not predicting second Scot ref at this stage, but constitutional settlement needs to change (inc London / FPTP?)21. Impacts across Europe will be substantial. We have taken 0.2% off growth and see larger political risks – particularly in Italy/France22. The region is capable of managing Brexit, and other crises in isolation. It may not be capable of managing several crises at once23. We expect things to hold together, but see major downside risks – include possibility EU wont deal, or that crises spin out of control

你说偏见、极端,也行。

Carmaker stays silent over future of Britain’s largest car plant

The British car industry issued a clear warning: leaving the EU could put jobs at risk.

But just a few days later Sunderland, the home of Nissan, delivered its verdict: a resounding 61.3 per cent of people voted for Brexit regardless.

Nissan has declined to comment on what Brexit means for the plant, a £3.85bn investment where 6,700 people work. But rumours are sweeping the production line.

Steven, a Nissan production line worker in his 30s who declined to give his surname, said he had woken the morning after voting for Brexit and thought: “What have I done?”

“A lot of people are worried,” he said. Another employee, an engineer who also declined to be named, said: “Personally, I voted to remain. I was surprised that the figures were so high for Leave.”

He said: “I’m very worried. If we do end up leaving it is going to be difficult for the Sunderland plant to remain competitive as most of our exported vehicles go to Europe. So it will be more difficult to get new vehicles into the plant.”

Steven said workers were already worried, noting that the constant fight to win new models against fierce competition from other Nissan/Renault alliance sites left the workers living under a “dark cloud” of possible job losses should the site not keep beating the opposition.

“We have had that threat of redundancies hanging over us for years,” he said. “We have that threat all the time; it’s just been another threat.”

Speaking to Nissan employees is difficult: the company declined to allow access to the plant, and most workers drive in and out of the complex.

The UK’s biggest single car making site, the plant produces one in three UK-made cars and last year exported 55 per cent of its 476,589 vehicles to the EU — about 250,000 cars.

We will never know which way its Sunderland employees — or the 20,000 other people in its north-east supply chain — voted. But according to Steven, the workers around him were outspoken in their desire for Brexit.

What happens next is a matter of politics not law.

The company did not wish to be seen to interfere in British politics, but Carlos Ghosn, the chief executive, said his preference was for the UK to remain.

Inside the plant, there was a video briefing for employees, but Steven said he had understood the message to be that how he voted was up to him. “I voted Leave because I want Britain to be Britain again,” he said.

North-east England, heavily dependent on inward investors for its manufacturing base, sends 58 per cent of its exported goods to the EU, far above the UK’s 49 per cent average. Sunderland alone is home to more than 80 overseas-owned companies employing 25,600 people. Yet within the north-east only one of 12 areas — Newcastle — backed Remain and then only narrowly.

Many Leave voters thought Nissan, now the north-east’s largest private sector employer, had too much at stake at Sunderland to pull out. This summer it marks 30 years of car production in the town.

It is unlikely Nissan would instantly withdraw from a site of such strategic significance; models include the Qashqai, the all-electric Leaf and its most recent massive investment, the Infiniti. But the threat is that, if hampered by adverse trade terms, the site may start to lose the fight for new models, ushering in decline.

Steven, unable to turn the clock back, said: “Hopefully our government, when they eventually get themselves sorted out, will put money into Nissan. If the government say don’t leave, we will make an offer you can’t refuse — hopefully that’s what’s going to happen.”

Another worker with many years of service at the company said money was still being invested and this was unlikely to change. Since Nissan workers commute from all over the north-east, Sunderland’s large majority for Leave did not necessarily reflect the vote at plant level.

He declined to say which way he had voted but commented; “We can only carry on as a plant and do the best we can.”