What's wrong with democracy?

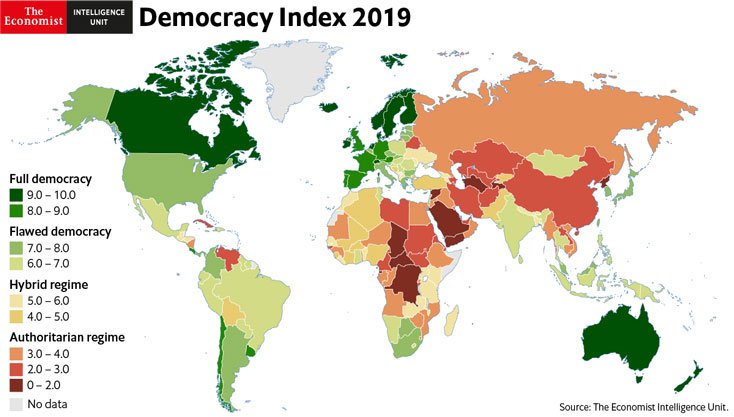

The Economist's Democracy Index 2019 confirms democracy's decline in Latin America and the world.

Democracia Abierta 19 February 2020, 3.29pm

The Economist Intelligence Unit

The Economist Intelligence Unit

Something is definitely wrong with liberal democracy across the world. The old idea that the end of the Cold War will bring some Hot Peace where everybody will embrace democracy and forget a brutal past of confrontation, authoritarianism, violent dictatorship and systematic violations of human rights has proven to be overestimated. Wild competition brought about by the final phases of the tech revolution that accelerated globalisation to a paroxysm has ended in a push for deglobalisation, introspection and refuge into the narrow boundaries of old nation states and identity politics.

As we enter the third decade of the 21st century, increasing inequality, wild neoliberalism, the rise of populisms, charismatic rogue leaders and widespread social unrest are the name of the game

Thus, across the world, last year has been defined by popular protests and democratic setbacks. So much so that the latest Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Report on Democracy, known and Democracy Index scored this year as the lowest since 2006. This is to say that 2019 was the worst in terms of global respect for democracy since its democracy index began. We are now in a position where only 5.7% of the world’s population lives in what this index considers a full democracy.

What about in Latin America? Thanks to the successes of third wave democratization in the region, since the 1980s, Latin America remains the most democratic emerging market region globally. But 2019 was a year of increasing democratic setbacks here too, the fourth year now of democratic decline, characterised by rising popular unrest across many countries of the region.

Nevertheless, digging below the main regional headlines, the picture is actually rather complex, with significant variations between countries. The fact that Chile and El Salvador improved their ranking left some questions about the methodology followed by The Economist, whilst the fact that Bolivia and Venezuela suffered from major setbacks is obvious.

The index is based on a number of indicators that aim to measure electoral process and pluralism, civil liberties, political culture, political participation and functioning of government. Global average scores fell in every single one of these categories except for improvements in political participation, manifested by the increased numbers of protests globally – in Hong Kong, Chile, France, Bolivia and in many more countries.

In fact, for Latin America, it was the increase in participation that stopped the region falling even further, suggesting that the challenges lie in institutional performance rather than in people’s faith in the democratic order.

So much so that the latest Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) Report on Democracy, known and Democracy Index scored this year as the lowest since 2006.

Global regression

Following a global trend, Latin American democracies performed worse in 2019 than in any previous year since 2006. Beyond Latin America, other emerging market countries also suffered from democratic setbacks. India, “the world’s largest democracy” experienced a significant drop in their score due to decreasing civil liberties led by its utranationalist leader Narenda Modi, and Poland became increasingly illiberal through the consolidation of media ownership and the restriction on independence for the judiciary. And there were low and worsening scores across almost all of sub-Saharan Africa.

The democratic crisis also extended into the so-called advanced countries. In particular, the USA has once again fallen short of being classified as a full democracy. US democracy has stagnated in the flawed democracy category after dropping there in 2016, reflecting a lack of confidence in government institutions in part due to the election of Donald Trump. The decline of such a powerful nation, historically acting as the chief exporter of liberal democracy to the world, is a reflection of the challenges of democracy, nationally and globally.

Participation through protest

Poor institutional performance meant that people had to make their voices heard through popular street protests. 2019 witnessed waves of mass mobilisation throughout the world that highlighted an unprecedented challenge to ineffective and narrow democracies, as well as to autocracies.

Globally, these protests have a number of similarities. They are an indicator of dissatisfaction with government performance thanks to dire long-term consequences of the post 2008 crisis-related austerity measures, corruption and failure to deal with issues such as violence and drug trafficking. And yet, there have also been structural failures on the part of governments and the judiciary, and a decline in the effective governance highlighted by the growing gap between the political elite and the general population, alongside a lack of political and societal accountability.

The EIU’s report correlates protest with improved participation and therefore a strengthening of democracy. But there is a contradiction here. It is true that protest indicates people’s desire to hold governments to account. But it is also the case that they are forced to do so on the streets precisely because the formal institutions for democracy are not doing their job adequately, whether because of bias, underfunding, inefficiency, or an excessive reliance on violence. This ambiguity is captured by the correlation the Report notes between improved participation score, on the one hand, and regression in the other measures of democracy, on the other.

Nowhere are these ambiguities better illustrated than in Chile. Despite the level of violence witnessed in the protests in Chile in 2019, the Economist measure of Chile’s increase in political participation seems to mean that it has moved from the category of flawed to full democracy. Yet there were 23 deaths during the Chilean protests caused by the aggression of Chile’s police and army. Should Chile’s democracy score go down because of the repression of protest rather than up because people took to the streets to protest against austerity and price rises? As democraciaAbierta argued in its previous analysis of the Democracy Index, these measurements focus on formal democracy and this has its limitations. Chile generally scores well in such Indexes, relative to the rest of the region, because its institutions appear stronger than elsewhere in Latin America. However, Chile’s response to the protests in 2019 highlights that despite their strong democratic institutions, Chile failed to respect human rights, and this should have been noted in the democracy index of 2019.

In Latin America, both government failures and an absence of accountability have contributed to the challenges democracy faces in the region.

For example, stagnant economic growth and the resulting austerity played a role in the protests in Ecuador, where a reduction in fuel subsidies, alongside other austerity measures included in an IMF plan to rescue its heavily-indebted economy, led to significant protests, particularly by indigenous communities politically active in the country. In Bolivia, meanwhile, protests erupted in response to the electoral crisis and growing divisions in Bolivian society.

Across the region, 2019 clearly demonstrated how democratic participation is still not effectively institutionalised through the formal mechanisms of democracy. Latin America certainly doesn’t lack an engaged civil society that is quick to mobilise, with consistent demand for democratic engagement and citizenship despite failing institutions. But here, political parties, very obedient to the power of oligarchies and vulnerable to corruption, usually fail to deliver, while popular opposition seems to lack enough political agency when it comes to present their alternative policies to elections.

A key factor in the declining regional score is drift towards authoritarianism in Bolivia and Venezuela.

Drift towards authoritarianism – Bolivia and Venezuela

A key factor in the declining regional score is drift towards authoritarianism in Bolivia and Venezuela, and the declining quality of electoral processes, which, in 2019, has been particularly evident in Bolivia.

The post-electoral crisis and apparent electoral fraud in Bolivia was a major focus in this year’s report and contributed to Latin America’s poor score. The debate revolved around whether the events that led to the removal of Evo Morales from the presidency constituted a coup or whether his government’s actions during the electoral process were the real threat to democracy that forced institutions to take action. According to the OAS mission observing the elections, there were severe irregularities in the count that suggested the possibility of electoral fraud.

This resulted in violent street protests, after which Morales lost the support of the military and judiciary and eventually resigned. The tensions around the elections were heightened by the fact that some sectors of Bolivian society were already dissatisfied with Morales’ will to secure a fourth term, despite the constitution originally permitting only two terms in office. Upcoming new elections might or might not restore confidence in the quality of Bolivian democracy.

The shift to authoritarianism has been even clearer in Venezuela, ongoing since the arrival of Hugo Chavez in 1999 and particularly after his successor Nicolás Maduro took office in 2013. But in 2019, the crisis got worse. Amidst the deep economic crisis and massive migration in Venezuela, the fight for power between Juan Guaidó and Nicolás Maduro highlights the weakness of democracy and the lack of communication that is needed for a restoration of truly democratic, fair elections due this year.

Central America

Central America vividly illustrates the changing and complex picture of Latin American democracy. The EIU suggests that Nicaragua, with its difficult political history of authoritarian rule, revolution and limited democratic transition, is giving way to authoritarianism. In fact, Nicaragua has been moving in this direction since the election of Daniel Ortega in 2007 and it is now almost at the bottom of the regional index, with only Cuba and Venezuela below it. Despite protests that began in 2018 and continued in 2019, Ortega has managed to hold on to power using paramilitary units to crack down on civilians and reduce civil liberties. Detention and mistreatment of your protesters and community leaders has further deteriorated what is left of Nicaraguan democracy.

Democratic regression in Guatemala and Honduras were also highlighted, with issues with free and fair elections, lack of accountability and corruption. For instance, the president’s brother was charged with drug trafficking in Honduras.

Overall, this report shows a worrying trend in Latin America as countries continue to slip away from democracy. This year has highlighted a worrying democratic regression but has also highlighted the importance of participation in standing up for democratic rights. It shows how the weak institutions in place in Latin America continue to be a problem for the state of democracy because they fail to reach the demands of the citizens in Latin America. Social unrest and street protests need to be treated as a fair expression of freedom and rights and have to be met by police with strict respect for the law and proportionate use of violence.

There is still a lot left to do to improve the state of democracy, not only in Latin America but globally. The demoralising result of this report should be considered a warning. The prospects of Donald Trump’s r-election in the US this year, plus the formalisation of Brexit, are not good news to the once powerful champions of liberal democracy.