美国读本 (The American Reader)

乔治.华盛顿 George Washington 告别演说 Farewell Address

https://usinfo.org/zhcn/gb/pubs/BasicReadings/49.htm#:~:text=

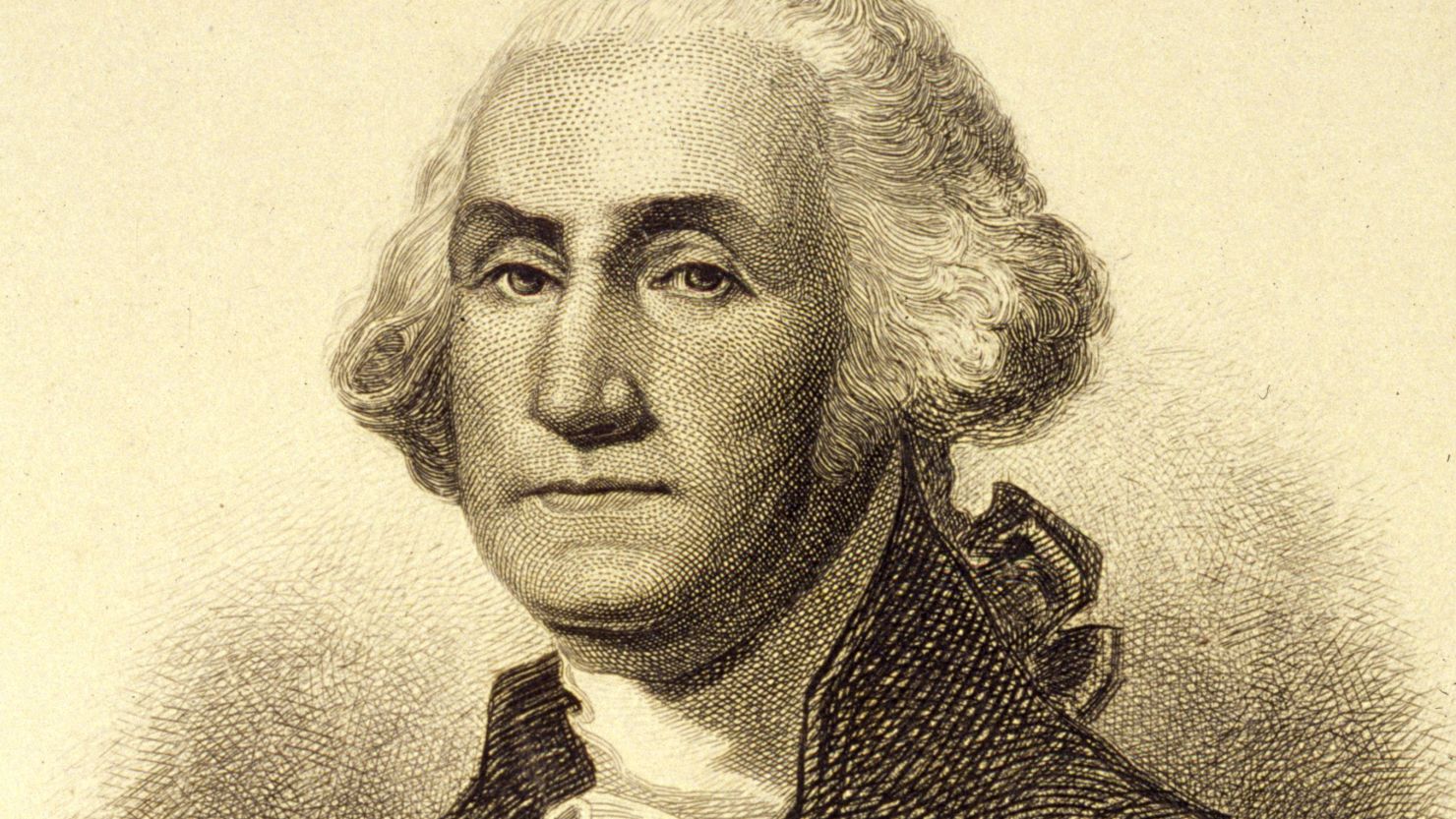

(American Memory Collection, Library of Congress)

我们处理外国事务的最重要原则,就是在与它们发展商务关系时,尽量避免与它们发生政治联系。

乔治.华盛顿(1732一1799)在领导革命军取得胜利并主持了成功的制宪会议之后,毫无异议地被选爲新国家的第一任总统。他勉强接受第二任四年的任期,但他拒绝连任第三任。在一个还是由国王、世袭酋长和小暴君们统治的世界里,华盛领作出放弃权力,让给民选继承人的决定表明美国的民主实验有了一个良好的开端。

在1796年9月17日向他的内阁所发表的告别演说中,华盛顿提出以下忠告:一、反对地方主义的危险;二、反对政治派系之争;三、保持宗教和道德作爲“人类幸福之重要支柱”,并促进建立“普及知识的机构”;四、与其它国家保持中立关系。他对于卷入国外争端的警告后来被称爲是“华盛顿的伟大法规”。直至第一次世界大战爲止,这条“伟大法规”一直是美国外交政策的主旨。

我们重新选举一位公民来主持美国政府的行政工作已爲期不远了,实际上,现在已经到了必须运用你们的思想来考虑将此重任付托给谁的时候了。因此,我觉得我应当向大家表明,尤其是因爲这样做可能使得公衆意见表达得更明确,那就是我已下定决心,谢绝把我列爲候选人……

政府的统一使大家结成一个民族,现在也爲你们所珍视。各位理应如此,因爲它是支撑你们真正独立的主要支柱,也是保证你们国内安定、国外和平、安全、繁荣以及你们所珍惜的自由的基石。然而,不难预见,会有某些力量试图削弱你们心里对这个真理的信念,这些力量起因不一,来源各异,但均煞费苦心,千方百计地産生作用。其所以如此,是因爲统一是你们政治堡垒中的一个攻击重点,内外敌人的炮火,会不断加紧(虽然常是隐蔽地和阴险地)攻击。因此,当前最重要的是你们应当正确估量民族团结对于你们集体和个人幸福的巨大价值。对于它你们应当怀有诚挚的、一贯的和坚定不移的忠诚;你们在思想上和言谈中应习惯于把它当作政治安定和繁荣的保护神,你们要小心翼翼地维护它。如果有人提到这种信念在某种情况下可以抛弃,即使那只是猜想,也不应当表示支持,如果有人企图使我国的一部分脱离其余部分,或想削弱现在联系各部份的神圣纽带,只要他们一提出来,你们就应当予以怒斥。

你们有对此给予同情和关怀的一切理由。既然你们因出生或归化而成爲同一国家的公民,这个国家就有权集中你们的情感。美国人这个称号是属于你们这些有国民身份的人,这个称号一定会提高你们爱国的光荣感,远胜过任何地方性的称号。你们之间除了极细微的差别之外,还有相同的宗教、礼议、习俗和政治原则。你们曾爲了一个共同的目标而奋斗,并共同获得胜利。你们所拥有的独立和自由,乃是你们群策群力,同甘苦、共患难的成果……

在研究那些可能扰乱我们联邦的种种原因时,使人想到一件令人严重关切的事,即以种种理由使党派具有地理差别的特征──北方的和南方的,东部的和西部的──企图这样做的人可能力图要借此造成一种信念,使人以爲地方之间真的存在着利益和观点的差异。一个党派想在某些地区获得影响而采取的功利手段之一,就是歪曲其它地区的观点和目标。这种歪曲引起的妒忌和不满,是防不胜防的,使那些本应亲如兄弟的人变得互不相容…….

爲了使你们的联邦有效力,能持久,一个代表全体的政府是不可少的。各地区结成的联盟,不论怎样严密,都不能充分代表这样的政府。这些联盟必定会经历古往今来所有联盟都曾经历过的背约和中断盟约的遭遇。由于明白了这个重要的真理,所以你们在最初尝试的基础上进行改善,通过了一部胜过从前的政府宪法,以期密切联合并更有效地管理大家的共同事务。这个政府是我们自己选择的,不曾受人影响,不曾受人威胁,是经过全盘研究和深思熟虑而建立的,它的原则和它的权力分配是完全自由的,它把安全和活力结合在一起,而且本身就含有修正其自身的规定。这样一个政府有充分的理由要求得到你们的信任和支持。尊重它的权威,服从它的法律,遵守它的规则,这些都是真正自由的基本准则所责成的义务。我们政治制度的基础是人民有权制定和变更其政府的宪法。可是宪法在经全民采取明确和正式的行动加以修改之前,任何人都对之负有神圣的履行义务。人民有权力和权利来建立政府,可这一观念是以每人有义务服从所建立的政府爲前提的……..

要保存你们的政府,要永久维持你们现在的幸福,你们不仅应当不断地反对那些不时发生的反对公认的政府的行爲,而且对那种要更新政府原则的风气,即使其借口看似有理,也应谨慎地予以抵制。他们进攻的方法之一,可能是采取改变宪法的形式,以损害这种体制的活力,从而把不能直接推翻的东西,暗中加以破坏。在你们可能被邀参与的所有变革中,应当记住,要确定政府的真正性质就像确定其它人类机构的性质一样,至少需要时间和习惯;应当记住,要检验一国现存政体的真正趋势,经验是最可靠的标准;应当记住,仅凭假设和意见便轻易变更,将会因假设和意见之无穷变化而招致无穷的变更;还要特别记住,在我们这样辽阔的国度里,要想有效地管理大家的共同利益,一个充满活力并能充分保障自由的政府是必不可少的……

我已经告诉你们在这个国家里存在着派系之争的危险,并特别提到以地区差别来分党立派的危险。现在让我以更全面的角度,以最郑重的态度告诫你们全面警惕派性的恶劣影响。不幸的是,这种派性与我们的本性是不可分割的,并扎根于人类思想里最强烈的欲望之中。它以各种不同的形式存在于所有政府机构里,尽管多少受到抑制、控制或约束;但那些常见的派性形式,往往是最令人厌恶的,而且确实是政府最危险的敌人…

它总是干扰公衆会议并削弱公衆的行政管理能力。它在社区里煽起毫无根据的猜忌和莫须有的惊恐;挑拨一派与另一派对立;有时还鼓起骚乱和暴动。它还爲外国影响和腐蚀打开方便之门,使之可轻易地通过派性的渠道深入到政府中来。这样,一个国家的政策和意志就得受制于另一国家的政策和意志……

在导致政治昌盛的各种意向和习惯中,宗教和道德是必不可少的支柱。那种想竭力破坏人类幸福的伟大支柱──人类与公民职责的最坚强支柱──的人,却妄想别人赞他爱国,必然是枉费心机。纯粹的政治家应当同虔诚的人一样,尊重并珍惜宗教和道德。它们与个人的和公衆的幸福之间的关系,即便写一本书也说不完。我们只须简单地问一句,如果宗教责任感不存在于法院藉以调查事件的誓言中,那么那里谈得上财産、名誉和生命的安全呢?我们还应当告诫自己不要耽于幻想,以爲道德可以不靠宗教维持。尽管高尚的教育对于特殊结构的心灵可能有所影响,但根据理智和经验,不容许我们期望在排除宗教原则的情况下,国民道德仍能普遍存在。

说道德是一个民意所归的政府所必需的原动力,这话实质上一点不错。这条准则可或多或少地适用于每一种类型的自由政府。凡是自由政府的忠实朋友,对于足以动摇它组织基础的企图,谁能熟视无睹呢?因此,大家应当把促进发展普及知识的机构作爲一个重要的目标。政府组织给舆论以力量,舆论也应相应地表现得更有见地,这是很重要的。

我们应当珍惜政府的财力,因爲这是力量和安全的重要源泉。保存财力的办法之一是尽量少动用它,并维护和平以避免意外开支;但也要记住,爲了防患于未然而及时拨款,往往可以避免支付更大的款项来消灾弭祸。我们同样也要避免债台高筑,爲此,不仅要减少开支,而且在和平时期要尽量去偿还不可避免的战争所带来的债务,不可吝啬抠搜,把我们自己应承受的负担留给后代……

一个自由民族应当经常警觉,提防外国势力的阴谋诡计(同胞们,我恳求你们相信我),因爲历史和经验证明,外国势力乃是共和政府最致命的敌人之一。不过这种提防,要想做到有效,就必须不偏不倚,否则它会成爲我们所要摆脱的势力的工具,而不是抵御那种势力的工事。过度偏好某一国和过度偏恶另一国,都会使受到这种影响的国家只看到一方面的危险,而掩盖甚至纵容另一方面所施的诡计。当我们所偏好的那个国家的爪牙和受他们蒙蔽的人,利用人民的赞赏和信任,而把人民的利益拱手出让时,那些会抵制该国诡计的爱国志士,反而极易成爲怀疑和憎恶的对象。

我们处理外国事务的最重要原则,就是在与它们发展商务关系时,尽量避免与它们发生政治联系。我们已订的条约,必须忠实履行,但以此爲限,不再增加。

欧洲有一套基本利益,这些利益对于我们毫无或极少关系。欧洲经常发生争执,其原因基本上与我们毫不相干。因此,如果我们卷进欧洲事务,与他们的政治兴衰人爲地联系在一起,或与他们友好而结成同盟,或与他们敌对而发生冲突,都是不明智的。

我国独处一方,远离它国,这种地理位置允许并促使我们奉行一条不同的路线。如果我们在一个称职的政府领导下,保持团结一致,那么,在不久的将来,我们就可以不怕外来干扰所造成的物质破坏;我们就可以来取一种姿态,使我们在任何时候决心保持中立时,都可得到它国的严正尊重;好战国家不能从我们这里获得好处时,也不敢轻易冒险向我们挑舋;我们可以在正义的指引下,依照自己的利益,在和平和战争问题上作出自己的抉择。

我们爲什么要摒弃这种特殊环境带来的优越条件呢?我们爲什么要放弃自己的立场而站到外国的立场上去呢?爲什么要把我们的命运同欧洲任何一部分的命运交织在一起,致使我们的和平与繁荣陷入欧洲的野心、竞争、利益关系、古怪念头,或反复无常的罗网之中呢?

虽然在检讨本人任期内所做的各事时,我未发觉有故意的错误,但我很明白我的缺点,并不以爲我没有犯过错误。不管这些错误是什么,我恳切地祈求上帝免除或减轻这些错误所可能産生的恶果。我也将怀着一种希望,愿我的国家永远宽恕这些错误,我秉持正直的热忱,献身效劳国家已经四十五载,我希望因爲能力薄弱而犯的过失,会随着我不久以后长眠地下而湮没无闻。

对于这件事也和其它事一样,均须仰赖祖国的仁慈。由于受到强烈的爱国之情的激励,──这种感情对于一个视祖国爲自己及历代祖先的故土的人来说,是很自然的。──我怀着欢欣的期待心情,指望在我切盼实现的退休之后,能与我的同胞们愉快地分享自由政府治下完善法律的温暖──这是我一直衷心向往的目标,并且我相信,这也是我们相互关怀、共同努力和赴场蹈火的理想报酬。

George Washington

"However [political parties] may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion."

George Washington FAREWELL ADDRESS | SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 1796

EDITORIAL NOTES

Washington is warning the American people against the negative impact that opposing political parties could have on the country. During his presidency he witnessed the rise of the Democratic-Republican party in opposition to the Federalists and worried that future political squabbles would undermine the concept of popular sovereignty in the United States.

Farewell Address, 19 September 1796

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-20-02-0440-0002

United States 19th September 1796

Friends & Fellow-Citizens

The period for a new election of a Citizen, to Administer the Executive government of the United States, being not far distant, and the time actually arrived, when your thoughts must be employed in designating the person, who is to be cloathed with that important trust, it appears to me proper, especially as it may conduce to a more distinct expression of the public voice, that I should now apprise you of the resolution I have formed, to decline being considered among the number of those, out of whom a choice is to be made.

I beg you, at the same time, to do me the justice to be assured, that this resolution has not been taken, without a strict regard to all the considerations appertaining to the relation, which binds a dutiful citizen to his country—and that, in withdrawing the tender of service which silence in my situation might imply, I am influenced by no diminution of zeal for your future interest; no deficiency of grateful respect for your past kindness; but am supported by a full conviction that the step is compatible with both.

The acceptance of, & continuance hitherto in, the office to which your Suffrages have twice called me, have been a uniform sacrifice of inclination to the opinion of duty, and to a deference for what appeared to be your desire. I constantly hoped, that it would have been much earlier in my power, consistently with motives, which I was not at liberty to disregard, to return to that retirement, from which I had been reluctantly drawn. The strength of my inclination to do this, previous to the last Election, had even led to the preparation of an address to declare it to you;1 but mature reflection on the then perplexed & critical posture of our Affairs with foreign Nations, and the unanimous advice of persons entitled to my confidence, impelled me to abandon the idea.

I rejoice, that the state of your concerns, external as well as internal, no longer renders the pursuit of inclination incompatible with the sentiment of duty, or propriety; & am persuaded whatever partiality may be retained for my services, that in the present circumstances of our country, you will not disapprove my determination to retire.

The impressions with which I first undertook the arduous trust, were explained on the proper occasion.2 In the discharge of this trust, I will only say, that I have with good intentions, contributed towards the Organization and administration of the government, the best exertions of which a very fallible judgment was capable. Not unconscious, in the out set, of the inferiority of my qualifications, experience in my own eyes, perhaps still more in the eyes of others, has strengthened the motives to diffidence of myself; and every day the encreasing weight of years admonishes me more and more, that the shade of retirement is as necessary to me as it will be welcome. Satisfied that if any circumstances have given peculiar value to my services, they were temporary, I have the consolation to believe, that while choice and prudence invite me to quit the political scene, patriotism does not forbid it.3

In looking forward to the moment, which is intended to terminate the career of my public life, my feelings do not permit me to suspend the deep acknowledgement of that debt of gratitude which I owe to my beloved country, for the many honors it has conferred upon me; still more for the stedfast confidence with which it has supported me; and for the opportunities I have thence enjoyed of manifesting my inviolable attachment, by services faithful & persevering, though in usefulness unequal to my zeal. If benefits have resulted to our country from these services, let it always be remembered to your praise, and as an instructive example in our annals, that, under circumstances in which the Passions agitated in every direction were liable to mislead,4 amidst appearances sometimes dubious, viscissitudes of fortune often discouraging, in situations in which not unfrequently want of Success has countenanced the spirit of criticism, the constancy of your support was the essential prop of the efforts, and a guarantee of the plans by which they were effected. Profoundly penetrated with this idea, I shall carry it with me to my grave, as a strong incitement to unceasing vows5 that Heaven may continue to you the choicest tokens of its beneficence—that your Union & brotherly affection my be perpetual—that the free constitution, which is the work of your hands, may be sacredly maintained—that its Administration in every department may be stamped with wisdom and virtue—that, in fine, the happiness of the people of these States, under the auspices of liberty, may be made complete, by so careful a preservation and so prudent a use of this blessing as will acquire to them the glory of recommending it to the applause, the affection—and adoption of every nation which is yet a stranger to it.

Here, perhaps, I ought to stop. But a solicitude for your welfare, which cannot end but with my life, and the apprehension of danger, natural to that solicitude, urge me on an occasion like the present, to offer to your solemn contemplation, and to recommend to your frequent review, some sentiments; which are the result of much reflection, of no inconsiderable observation, and which appear to me all important to the permanency of your felicity as a People. These will be offered to you with the more freedom, as you can only see in them the disinterested warnings of a parting friend, who can possibly have no personal motive to biass his counsel. Nor can I forget, as an encouragement to it, your endulgent reception of my sentiments on a former and not dissimilar occasion.6

Interwoven as is the love of liberty with every ligament of your hearts, no recommendation of mine is necessary to fortify or confirm the attachment.

The Unity of Government which constitutes you one people is also now dear to you. It is justly so; for it is a main Pillar in the Edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home, your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty which you so highly prize. But as it is easy to foresee, that from different causes & from different quarters, much pains will be taken, many artifices employed, to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth; as this is the point in your political fortress against which the batteries of internal and external enemies will be most constantly and actively (though often covertly & insidiously) directed, it is of infinite moment, that you should properly estimate the immense value of your national Union, to your collective & individual happiness; that you should cherish a cordial, habitual & immoveable attachment7 to it; accustoming yourselves to think and speak of it as of the Palladium of your political safety and prosperity; watching for its preservation with jealous anxiety; discountenancing whatever may suggest even a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and indignantly frowning upon the first dawning of every attempt to alienate any portion of our Country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the various parts.

For this you have every inducement of sympathy and interest. Citizens by birth or choice, of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of AMERICAN, which belongs to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same Religion, Manners, Habits & political Principles. You have in a common cause fought and triumphed together—the independence & Liberty you possess are the work of joint councils, and joint efforts—of common dangers, sufferings and successes.

But these considerations, however powerfully they address themselves to your sensibility are greatly outweighed by those which apply more immediately to your Interest. Here every portion of our country finds the most commanding motives for carefully guarding & preserving the Union of the whole.

The North, in an unrestrained intercourse with the South, protected by the equal Laws of a common government, finds in the productions of the latter,8 great additional resources of maritime & commercial enterprise and precious materials of manufacturing industry. The South in the same Intercourse, benefitting by the Agency of the North, sees its agriculture grow & its commence expand. Turning partly into its own channels the seamen of the North, it finds its particular navigation envigorated; and while it contributes, in different ways, to nourish & increase the general mass of the national navigation, it looks forward to the protection of a maritime strength, to which itself is unequally adapted. The East, in a like intercourse with the West, already finds, and in the progressive improvement of interior communications, by land & water, will more & more find a valuable vent for the commodities which it brings from abroad, or manufactures at home. The West derives from the East supplies requisite to its growth & comfort—and what is perhaps of still greater consequence, it must of necessity owe the secure enjoyment of indispensable outlets for its own productions to the weight, influence, and the future maritime strength of the Atlantic side of the Union, directed by an indissoluble community of Interest as one Nation. Any other tenure by which the West can hold this essential advantage, whether derived from its own seperate strength, or from an apostate & unnatural connection with any foreign Power, must be intrinsically precarious.9

While then every part of our country thus feels an immediate & particular Interest in Union, all the parts combined cannot fail to find in the united mass of means & efforts greater strength, greater resource, proportionably greater security from external danger, a less frequent interruption of their Peace by foreign Nations; and, what is of inestimable value! they must derive from Union an exemption from those broils and Wars between themselves, which so frequently10 afflict neighbouring countries, not tied together by the same government; which their own rivalships alone would be sufficient to produce, but which opposite foreign alliances, attachments & intriegues would stimulate and imbitter. Hence likewise they will avoid the necessity of those overgrown military establishments, which under any form of Government are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to Republican Liberty: In this sense it is, that your Union ought to be considered as a main prop of your liberty, and that the love of the one ought to endear to you the preservation of the other.

These considerations speak a persuasive language to every reflecting & virtuous mind, and exhibit the continuance of the UNION as a primary object of Patriotic desire. Is there a doubt, whether a common government can embrace so large a sphere? Let experience solve it. To listen to mere speculation in such a case were criminal. We are authorized to hope that a proper organization of the whole, with the auxiliary agency of governments for the respective Subdivisions, will afford a happy issue to the experiment. ’Tis well worth a fair and full experiment.11 With such powerful and obvious motives to Union, affecting all parts of our country, while experience shall not have demonstrated its impracticability, there will always be reason to distrust the patriotism of those, who in any quarter may endeavor to weaken its bands.12

In contemplating the causes wch may disturb our Union, it occurs as matter of serious concern, that any ground should have been furnished for characterizing parties by Geographical discriminations—Northern and Southern—Atlantic and Western;13 whence designing men may endeavour to excite a belief that there is a real difference of local interests and views. One of the expedients of party to acquire influence, within particular districts, is to misrepresent the opinions & aims of other Districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heart burnings which spring from these misrepresentations. They tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection. The Inhabitants of our Western country have lately had a useful lesson on this head. They have seen, in the Negociation by the Executive, and in the unanimous ratification by the Senate, of the Treaty with Spain, and in the universal satisfaction at that event, throughout the United States, a decisive proof how unfounded were the suspicions propagated among them of a policy in the General Government and in the Atlantic states unfriendly to their Interests in regard to the Mississippi. They have been witnesses to the formation of two Treaties, that with G: Britain and that with Spain, which secure to them every thing they could desire, in respect to our Foreign relations, towards confirming their prosperity.14 Will it not be their wisdom to rely for the preservation of these advantages on the Union by wch they were procured? Will they not henceforth be deaf to those advisers, if such there are, who would sever them from their Brethren and connect them with Aliens?

To the efficacy and permanency of Your Union, a Government for the whole is indispensable. No Alliances however strict between the parts can be an adequate substitute. They must inevitably experience the infractions & interruptions which all Alliances in all times have experienced. Sensible of this momentous truth, you have improved upon your first essay, by the adoption of a Constitution of Government, better calculated than your former for an intimate Union, and for the efficacious management of your common concerns. This government, the offspring of our own choice uninfluenced and unawed, adopted upon full investigation and mature deliberation, completely free in its principles, in the distribution of its powers, uniting security with energy, and containing within itself a provision for its own amendment, has a just claim to your confidence and your support. Respect for its authority, compliance with its Laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true Liberty. The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their Constitutions of Government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, ’till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole People, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the People to establish Government presupposes the duty of every Individual to obey the established Government.

All obstructions to the execution of the Laws, all combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, controul counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the Constituted authorities are distructive of this fundamental principle and of fatal tendency. They serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force—to put in the place of the delegated will of the Nation, the will of a party; often a small but artful and enterprizing minority of the Community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the Mirror of the ill concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the Organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common councils and modefied by mutual interests. However combinations or Associations of the above description may now & then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the Power of the People, & to usurp for themselves the reins of Government; destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

Towards the preservation of your Government and the permanency of your present happy state, it is requisite, not only that you steadily discountenance irregular oppositions to its acknowledged authority, but also that you resist with care the spirit of innovation upon its principles however specious the pretexts. One method of assault may be to effect, in the forms of the Constitution, alterations which will impair the energy of the system, and thus to undermine what cannot be directly overthrown. In all the changes to which you may be invited, remember that time and habit are at least as necessary to fix the true character of Governments, as of other human institutions—that experience is the surest standard, by which to test the real tendency of the existing Constitution of a country—that facility in changes upon the credit of mere hypotheses & opinion exposes to perpetual change, from the endless variety of hypotheses and opinion: and remember, especially, that for the efficient management of your common interests, in a country so extensive as ours, a Government of as much vigour as is consistent with the perfect security of Liberty is indispensable—Liberty itself will find in such a Government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest Guardian. It is indeed little else than a name, where the Government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of the Society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and property.15

I have already intimated to you the danger of Parties in the State, with particular reference to the founding of them on Geographical discriminations. Let me now take a more comprehensive view, & warn you in the most solemn manner against the baneful effects of the Spirit of Party, generally.

This spirit, unfortunately, is inseperable from our nature, having its root in the strongest passions of the human Mind. It exists under different shapes in all Governments, more or less stifled, controuled, or repressed; but in those of the popular form it is seen in its greatest rankness and is truly their worst enemy.16

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge natural to party dissention, which in different ages & countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders & miseries, which result, gradually incline the minds of men to seek security & repose in the absolute power of an Individual: and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty.

Without looking forward to an extremity of this kind (which nevertheless ought not to be entirely out of sight) the common & continual mischiefs of the spirit of Party are sufficient to make it the interest and the duty of a wise People to discourage and restrain it.

It serves always to distract the Public Councils and enfeeble the Public Administration. It agitates the Community with ill founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot & insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence & corruption, which find a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions. Thus the policy and the will of one country, are subjected to the policy and will of another.

There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful checks upon the Administration of the Government and serve to keep alive the spirit of Liberty. This within certain limits is probably true—and in Governments of a Monarchical cast Patriotism may look with endulgence, if not with favour, upon the spirit of party. But in those of the popular character, in Governments purely elective, it is a spirit not to be encouraged. From their natural tendency, it is certain there will always be enough of that spirit for every salutary purpose. And there being constant danger of excess, the effort ought to be, by force of public opinion, to mitigate & assuage it. A fire not to be quenched; it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest instead of warming it should consume.

It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free Country should inspire caution, in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective Constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the Powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create whatever the form of government, a real despotism. A just estimate of that love of power, and proneness to abuse it, which predominates in the human heart is sufficient to satisfy us of the truth of this position. The necessity of reciprocal checks in the exercise of political power; by dividing and distributing it into different depositories, & constituting each the Guardian of the Public Weal against invasions by the others, has been evinced by experiments ancient & modern; some of them in our country & under our own eyes. To preserve them must be as necessary as to institute them. If in the opinion of the People, the distribution or modification of the Constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit which the use can at any time yield.

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labour to subvert these great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men & citizens. The mere Politician, equally with the pious man ought to respect & to cherish them. A volume could not trace all their connections with private & public felicity. Let it simply be asked where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths, which are the instruments of investigation in Courts of Justice? And let us with caution indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure—reason & experience both forbid us to expect that National morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

’Tis substantially true, that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule indeed extends with more or less force to every species of free Government. Who that is a sincere friend to it can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric?17

Promote then as an object of primary importance, Institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

As a very important source of strength & security cherish public credit. One method of preserving it is to use it as sparingly as possible: avoiding occasions of expence by cultivating peace, but remembering also that timely disbursements to prepare for danger frequently prevent much greater disbursements to repel it—avoiding likewise the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expence, but by vigorous exertions in time of Peace to discharge the Debts which unavoidable wars may have occasioned, not ungenerously throwing upon posterity the burthen which we ourselves ought to bear. The execution of these maxims belongs to your Representatives, but it is necessary that public opinion should cooperate.18 To facilitate to them the performance of their duty, it is essential that you should practically bear in mind, that towards the payment of debts there must be Revenue—that to have Revenue there must be taxes—that no taxes can be devised which are not more or less inconvenient & unpleasant—that the intrinsic embarrassment inseperable from the selection of the proper objects (which is always a choice of difficulties) ought to be a decisive motive for a candid construction of the conduct of the Government in making it, and for a spirit of acquiescence in the measures for obtaining Revenue which the public exigencies may at any time dictate.

Observe good faith & justice towds all Nations cultivate peace & harmony with all—Religion & morality enjoin this conduct; and can it be that good policy does not equally enjoin it? It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and, at no distant period, a great Nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a People always guided by an exalted justice & benevolence. Who can doubt that in the course of time and things the fruits of such a plan would richly repay any temporary advantages wch might be lost by a steady adherence to it? Can it be, that Providence has not connected the permanent felicity of a Nation with its virtue? The experiment, at least, is recommended by every sentiment which ennobles human Nature. Alas! is it rendered impossible by its vices?

In the execution of such a plan, nothing is more essential than that permanent, inveterate antipathies against particular Nations and passionate attachments for others should be excluded; and that in place of them just & amicable feelings towards all should be cultivated. The Nation, which indulges towards another an habitual hatred, or an habitual fondness, is in some degree a slave. It is a slave to its animosity or to its affection, either of which is sufficient to lead it astray from its duty and its interest. Antipathy in one Nation against another19 disposes each more readily to offer insult and injury, to lay hold of slight causes of umbrage, and to be haughty and intractable, when accidental or trifling occasions of dispute occur. Hence frequent collisions, obstinate envenomed and bloody contests. The Nation, prompted by ill will & resentment sometimes impels to War the Government, contrary to the best calculations of policy. The Government sometimes participates in the national propensity, and adopts through passion what reason would reject; at other times, it makes the animosity of the nation subservient to projects of hostility instigated by pride, ambition and other sinister & pernicious motives. The peace often, sometimes perhaps the Liberty, of Nations has been the victim.

So likewise, a passionate attachment of one Nation for another produces a variety of evils. Sympathy for the favourite nation, facilitating the illusion of an imaginary common interest, in cases where no real common interest exists, and infusing into one the enmities of the other, betrays the former into a participation in the quarrels & Wars of the latter, without adequate inducement or justification: It leads also to concessions to the favourite Nation of priviledges denied to others, which is apt doubly to injure the Nation making the concessions—by unnecessarily parting with what ought to have been retained—& by exciting jealousy, ill will, and a disposition to retaliate, in the parties from whom eql priviledges are withheld: And it gives to ambitious, corrupted, or deluded citizens (who devote themselves to the favourite Nation) facility to betray, or sacrifice the interests of their own country, without odium, sometimes even with popularity; gilding with the appearances of a virtuous sense of obligation a commendable deference for public opinion, or a laudable zeal for public good, the base or foolish compliances of ambition, corruption or infatuation.

As avenues to foreign influence in innumerable ways, such attachments are particularly alarming to the truly enlightened and independent Patriot. How many opportunities do they afford to tamper with domestic factions, to practice the arts of seduction, to mislead public opinion, to influence or awe the public Councils! Such an attachment of a small or weak, towards a great & powerful Nation, dooms the former to be the satellite of the latter.

Against the insidious wiles of foreign influence (I conjure you to believe me fellow citizens) the jealousy of a free people ought to be constantly awake; since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of Republican Government. But that jealousy to be useful must be impartial; else it becomes the instrument of the very influence to be avoided, instead of a defence against it. Excessive partiality for one foreign nation and excessive dislike of another, cause those whom they actuate to see danger only on one side, and serve to veil and even second the arts of influence on the other. Real Patriots, who may resist the intrigues of the favourite, are liable to become suspected and odious; while its tools and dupes usurp the applause & confidence of the people, to surrender their interests.

The great rule of conduct for us, in regard to foreign Nations is in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements let them be fulfilled with20 perfect good faith. Here let us stop.

Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence therefore it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations & collisions of her friendships, or enmities.

Our detached & distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one People, under an efficient government, the period is not far off, when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when21 belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation;22 when we may choose peace or War, as our interest guided by justice shall counsel.

Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, Rivalship, Interest, Humour or Caprice?

’Tis our true policy to steer clear of permanent Alliances, with any portion of the foreign world—So far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it—for let me not be understood as capable of patronising infidility to existing engagements. (I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy). I repeat it therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But in my opinion, it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Taking care always to keep ourselves, by suitable establishments, on a respectably defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.

Harmony, liberal intercourse with all Nations, are recommended by policy, humanity and interest. But even our Commercial policy should hold an equal and impartial hand: neither seeking nor granting exclusive favours or preferences; consulting the natural course of things; diffusing & diversifying by gentle means the streams of Commerce, but forcing nothing; establishing, with Powers so disposed—in order to give trade a stable course, to define the rights of our merchants, and to enable the Government to support them—conventional rules of intercourse, the best that present circumstances and mutual opinion will permit, but temporary, & liable to be from time to time abandoned or varied, as experience and circumstances shall dictate; constantly keeping in view; that ’tis folly in one Nation to look for disinterested favors from another—that it must pay with a portion of its Independence for whatever it may accept under that character—that by such acceptance, it may place itself in the condition of having given equivalents for nominal favours and yet of being reproached with ingratitude for not giving more. There can be no greater error than to expect, or calculate upon real favours from Nation to Nation. ’Tis an illusion which experience must cure, which a just pride ought to discard.

In offering to you, my Countrymen, these counsels of an old and affectionate friend, I dare not hope they will make the strong and lasting impression, I could wish—that they will controul the usual current of the passions, or prevent our Nation from running the course which has hitherto marked the Destiny of Nations: But if I may even flatter myself, that they may be productive of some partial benefit, some occasional good, that they may now & then recur to moderate the fury of party spirit, to warn against the mischiefs of foreign Intriegue, to guard against the Impostures of pretended patriotism—this hope will be a full recompence for the solicitude for your welfare, by which they have been dictated.

How far in the discharge of my Official duties, I have been guided by the principles which have been delineated, the public Records and other evidences of my conduct must witness to You and to the world. To myself, the assurance of my own conscience is, that I have at least believed myself to be guided by them.

In relation to the still subsisting War in Europe, my Proclamation of the 22d of April 1793 is the index to my Plan. Sanctioned by your approving voice and by that of your Representatives in both Houses of Congress, the spirit of that measure has continually governed me; uninfluenced by any attempts to deter or divert me from it.23

After deliberate examination with the aid of the best lights I could obtain24 I was well satisfied that our country, under all the circumstances of the case, had a right to take, and was bound in duty and interest, to take a Neutral position. Having taken it, I determined, as far as should depend upon me, to maintain it, with moderation, perseverence & firmness.

The considerations which respect the right to hold this conduct, it is not necessary on this occasion to detail. I will only observe, that according to my understanding of the matter, that right, so far from being denied by any of the Belligerent Powers has been virtually admitted by all.25

The duty of holding a Neutral conduct may be inferred, without any thing more, from the obligation which justice and humanity impose on every Nation, in cases in which it is free to act, to maintain inviolate the relations of Peace and amity towards other Nations.

The inducements of interest for observing that conduct will best be referred to your own reflections & experience. With me, a predominant motive has been to endeavour to gain time to our country to settle & mature its yet recent institutions, and to progress without interruption, to that degree of strength & consistency, which is necessary to give it, humanly speaking, the command of its own fortunes.

Though in reviewing the incidents of my Administration, I am unconscious of intentional error—I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope that my Country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that after forty five years of my life dedicated to its Service, with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.26

Relying on its kindness in this as in other things, and actuated by that fervent love towards it, which is so natural to a man, who views in it the native soil of himself and his progenitors for several Generations; I anticipate with pleasing expectation that retreat, in which I promise myself to realize, without alloy, the sweet enjoyment of partaking, in the midst of my fellow Citizens, the benign influence of good Laws under a free Government—the ever favourite object of my heart, and the happy reward, as I trust, of our mutual cares, labours and dangers.27

Go: Washington

ADS, NN; LB (dated 17 Sept.), DLC:GW. The address was first printed in Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser for 19 Sept. 1796, where it was given a date of 17 September. Except for the date change and variations in capitalization, punctuation, and spelling, the published version reproduced the ADS.

The most important of the various deletions and alterations on the manuscript are indicated in the notes below. For the other changes, see Paltsits, Farewell Address, 105–36 (facsimile), and 139–59 (transcription).

On a copy of Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser now at NNGL, GW wrote a note, apparently providing directions for its entry into a letter book: “The Letter containd in this Gazette—Addressed to the People of the United States is to be Recorded and in the Order of its da〈te〉.

“Let it have a blan〈k〉 Page before & after so as to stand distinct as it were. Let it be wrote with a letter larger & fully than the common recordi〈n〉g hand—And where words are Printed with capital letters it is to be done so in Recording 〈th〉is 〈letter〉 and those other wo〈rd〉s that are printed in Italicks, must 〈be d〉rew underneath and streight by a Ruler.”

1. For that draft, see the enclosure printed with James Madison to GW, 20 June 1792.

2. GW alluded to his first inaugural address, 30 April 1789.

3. At this point GW struck out eleven lines of text and a marginal note with an explanation: “obliterated to avoid the imputation of affected modesty.” The deleted text reads: “May I also have that of knowing in my retreat, that the involuntary errors, I have probably committed, have been the sources of no serious or lasting mischief to our country. I may then expect to realise, without alloy, the sweet enjoyment of partaking, in the midst of my fellow citizens, the benign influence of good laws under a free government; the ever favorite object of my heart, and the happy reward, I trust, of our mutual cares, dangers & labours.”

4. The preceding word replaced three words—“wander & fluctuate”—that GW had struck out.

5. At this point GW struck a parenthetical phrase: “the only return I can henceforth make.”

6. GW is referring to his circular letter to the states announcing his resignation from the army in June 1783 (see GW’s Draft for a Farewell Address, n.8, printed as an enclosure with GW to Alexander Hamilton, 15 May).

7. The remainder of this paragraph replaced text that read: “that you should accustom yourselves to reverance it as the palladium of your political safety and prosperity, adapting constantly your words and actions to that momentous idea that you should watch for its preservation with jealous anxiety, discountenance whatever may suggest a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned; and frown upon the first dawning of any attempt to alienate any portion of our Country from the rest, or to enfeeble the sacred ties which now link together the several parts.”

8. GW struck out “many of them peculiar” at this point.

9. Here GW struck the following elaboration: “liable every moment to be disturbed by the fluctuating combinations of the primary interests of Europe, which must be expected to regulate the conduct of the Nations of which it is composed.”

10. GW inserted the preceding two words to replace “inevitably,” which he struck out.

11. Here GW struck the following sentences: “It may not impossibly be found, that the spirit of party, the machinations of foreign powers, the corruption and ambition of individual citizens, are more formidable adversaries to the unity of our Empire, than any inherent difficulties in the scheme. Against these, the mounds of national opinion, national sympathy and national jealousy ought to be raised.”

12. At this point GW struck the following paragraph and a marginal note with an explanation: “not important enough.” The paragraph reads: “Besides the more serious causes already hinted as threatening our Union, there is one less dangerous, but sufficiently dangerous to make it prudent to be upon our guard against it. I allude to the petulence of party differences of opinions. It is not uncommon to hear the irritations which these excite vent themselves in declarations, that the different parts of the United States are ill affected to each other in menaces, that the Union will be dissolved by this or that measure. Intimations like these are as indiscreet as they are intemperate. Though frequently made with levity, & without any really evil intention, they have a tendency to produce the consequence which they indicate. They teach the minds of men to consider the Union as precarious—as an object to which they ought not to attach their hopes and fortunes, and thus chill the sentiment in its favor. By alarming the pride of those to whom they are addressed, they set ingenuity at work to depreciate the value of the thing and to discover reasons of indifference towards it. This is not wise. It will be much wiser to habituate ourselves to reverence the Union as the palladium of our national happiness—to accomodate constantly our words and actions to that idea—and to discountenance whatever may suggest a suspicion that it can in any event be abandoned.”

The surviving draft in Hamilton’s writing continued with another sentence at this point, preceding the paragraph deleted by GW. That omitted sentence reads: “And by all the love I bear you My fellow Citizens I conjure you as often as it appears to frown upon the attempt.”

13. GW completed this sentence with words inserted to replace two struck-out sentences: “These discriminations, the mere contrivance of the spirit of Party, (always dexterous to seize every handle by which the passions can be wielded, and too skilful not to turn to account the sympathy of neighbourhood), have furnished an argument against the Union, as evidence of a real difference of local interests and views; and serve to hazard it, by organizing large districts of country under the leaders of contending factions, whose rivalships, prejudices & schemes of ambition, rather than the true Interests of the Country, will direct the use of their influence. If it be possible to correct this poison in the habit of our body politic, it is worthy the endeavors of the moderate and the good to effect it.”

14. In Article IV of the 27 Oct. 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo, Spain agreed that navigation of the Mississippi River “in its whole breadth from it source to the Occean” would be free to U.S. citizens, and in Article XXII of the treaty Spain granted to U.S. citizens for three years the right to deposit their merchandise at New Orleans and reship it “without paying any other duty than a fair price for the hire of the stores” with a further promise to continue that right or to offer “an equivalent establishment” on the Mississippi (Miller, Treaties, 321–22, 337). For the Jay Treaty of 19 Nov. 1794 with Great Britain, GW may have been referring to Article II, promising British withdrawal from frontier posts, and Article III, reaffirming that navigation of the Mississippi River would remain open to citizens of both countries with the right to cross borders and freely carry on commerce, except within the limits of Hudson’s Bay Company (Miller, Treaties, 246–48).

15. GW inserted this sentence to replace one that he struck out: “Owing to you as I do, a frank and free disclosure of my heart, I shall not conceal from you the belief I entertain, that your Government as at present constructed is far more likely to prove too feeble than too powerful.”

16. Here GW struck six sentences: “In Republics of narrow extent, it is not difficult for those who at any time hold the reins of Power, and command the ordinary public favor, to overturn the established Constitution, in favor of their own aggrandisement. The same thing may likewise be too often accomplished in such Republics, by partial combinations of men, who though not in Office, from birth, riches or other sources of distinction, have extraordinary influence & numerous adherents. By debauching the military force, by surprising some commanding citadel, or by some other sudden & unforeseen movement, the fate of the Republic is decided. But in Republics of large extent, usurpations can scarcely make its way through these avenues. The powers and opportunities of resistance of a wide extended and numerous nation, defy the successful efforts of the ordinary military force, or of any Collections which wealth and patronage may call to their aid. In such Republics, it is safe to assert, that the conflicts of popular factions are the chief, if not the only inlets, of usurpation and Tyranny.”

17. At this point GW struck out a paragraph and a marginal note with an explanation: “not sufficiently important.” The paragraph reads (text in angle brackets is from the transcription by Paltsits): “Cultivate industry and frugality, as auxiliaries to good morals 〈& sources of private & public prosperity. Is there no room to regret that our propensity to expence exceeds our means for it? Is there not more luxury among us, and more diffusively, than suits the actual stage of our national progress?〉 Whatever may be the apology for luxury in a country, mature in the arts which are its ministers, and the 〈cause〉 of national opulence—Can it promote the advantage of a young country, almost wholly Agricultural, in the infancy of the Arts, and certainly not in the maturity of wealth?” The portion of the deleted text following the word “frugality” was at the top of a page, and GW used wafers to attach over that deleted text the paragraph that now follows.

18. The preceding sentence does not appear in the surviving Hamilton draft. It may, however, have been influenced by a marginal note that Hamilton had written beside an earlier paragraph: “ordinary management of affairs to be left to Represent” (Hamilton Papers, 20:275).

19. GW struck text reading “begets of course a similar sentiment in that other” at this point.

20. GW struck out a qualifying phrase—“circumspection indeed, but with”—at this point.

21. GW struck out “neither of two” at this point.

22. GW struck out “to throw our weight into the opposite scale” at this point.

23. GW is referring to the Neutrality Proclamation.

24. At this point, GW struck a parenthetical phrase: “and from men disagreeing in their impressions of the origin progress and nature of that war.”

25. This paragraph was attached by wafers above a paragraph on the original page. A marginal note explains: “This is the first draught and it is questionable which of the two is to be preferred.” The final text includes two minor edits made by GW: the insertion of “it is not necessary” to replace “some of them of a delicate nature, would be improperly the subject of explanation,” which he struck out, and the insertion of the words “to detail” after “this occasion.” On the original page, GW had started with the same base text and edited it more extensively to read: “The considerations, which respect the right to hold this conduct, would be improperly the subject of particular discussion on this occasion.—I will barely observe, that to me they appeared warranted by well established principles of the Laws of Nations, as applicable to the nature of our alliance with France in connection with the circumstances of the War and the relative situations of the contracting parties” (the transcription is taken from Paltsits).

This paragraph and the two paragraphs following do not appear on the surviving draft in Hamilton’s writing.

26. Following this paragraph, GW deleted a paragraph and a marginal note with an explanation: “This paragraph may have the appearance of self distrust and mere vanity.” To draw the printer to the final paragraph of the address, he wrote here “Relying &a” with a bracketed note “see the other side.” The deleted paragraph reads: “May I, without the charge of ostentation, add, that neither ambition nor interest has been the impelling cause of my actions—that I have never designedly misused any power confided to me, nor hesitated to use one, where I thought it could redound to your benefit? May I, without the appearance of affectation, say that the fortune with which I came into office is not bettered otherwise than by that improvement in the value of property, which the quick progress & uncommon prosperity of our country have produced? May I still further add, without breach of delicacy, that I shall retire without cause for a blush, with sentiment alien to the fervor of those vows for the happiness of his country so natural to a citizen who sees in it the native soil of his progenitors and himself for four generations.”

27. This paragraph has a bracketed note in the right margin that reads: “continuation of the paragraph preceeding the last, ending with the word rest.”