欧洲民主倒退的本质

https://carnegieeurope.eu/2018/07/24/nature-of-democratic-backsliding-in-europe-pub-76868

斯塔凡·林德伯格 2018 年 7 月 24 日

Staffan Ingemar Lindberg

Professor Department of Political Science

摘要:欧洲民主正在衰落,越来越独裁的领导人通过针对媒体自由、个人权利和法治来破坏冷战后的自由秩序。

重塑欧洲民主

本文是重塑欧洲民主项目的一部分,该项目是卡内基民主、冲突和治理项目和卡内基欧洲的一项倡议。

在欧洲,与世界上大多数其他地区一样,民主正在倒退,独裁正在抬头。 然而欧洲面临的挑战尤其值得注意。 尽管人们普遍认为民主倒退始于选举问题,但其他政治因素——例如侵犯个人权利和言论自由——是欧洲民主困境的核心。

斯塔凡·I·林德伯格 (Staffan I. Lindberg) 是民主多样性 (V-Dem) 研究所所长,也是哥德堡大学政治学教授。

民主多样性 (V-Dem) 指数是哥德堡大学 V-Dem 研究所的标志性产品,通过对七种不同民主类型的独特关注来考察全球民主状况。 V-Dem 最近发布了 2017 年数据和年度《2018 年民主报告》,其中使用了 180 个国家 3,200 多名学者提供的评级汇总后的 400 多个民主、人权、公民自由和自由细节的详细指标; 近五十个反映民主组成部分的指数,如问责制、妇女赋权、言论自由、廉洁选举等; 以及民主的五个主要指数(选举民主、自由民主、参与民主、协商民主和平等民主),为全球民主的状况,特别是欧洲民主的形态提供了新的见解。

V-Dem 的数据显示,全球独裁化浪潮——民主品质的下降,可能导致民主的崩溃——在共产主义崩溃和民主在全球传播后不到三十年就显现出来,为二十一世纪的主导国家带来了巨大希望。 通过自由民主。 过去十年,洪都拉斯、尼加拉瓜、俄罗斯、委内瑞拉、土耳其和乌克兰的威权主义崛起,伴随着巴西、印度、以色列和现在的美国等国家的大幅倒退,证明了《世界经济展望》中表达的乐观主义的错误。 20世纪90年代。 世界是否应该真正对欧洲民主的未来感到震惊?

令人警醒的全球形势

第三次全球民主化浪潮始于 20 世纪 70 年代中期,并在 1980 年代和 1990 年代获得动力,并在 1993 年至 1999 年间达到顶峰。在此期间,有 70 个国家在 V-Dem 的自由民主指数上每年取得显着进步,而只有 4 个国家达到了这一水平。 有六个国家逐年倒退。 这种民主进步对恶化的主导地位实际上从1978年一直持续到2010年左右。从那时起,民主进步的下降趋势变得明显,而民主倒退的国家数量却在增加。 2017年,倒退的国家数量四十年来首次与进步的国家数量相匹配。

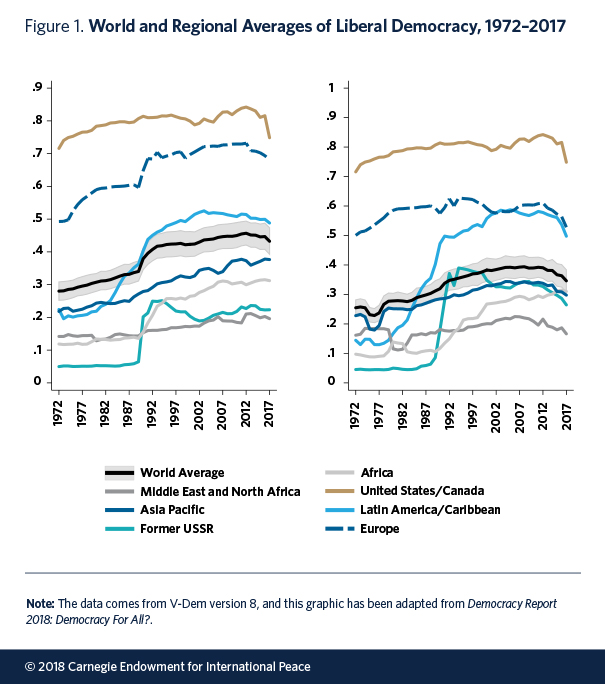

根据 V-Dem 2018 年的数据,1972 年至 2017 年世界民主的总体水平可以从两个互补指标的角度来看待(见图 1):各国的传统平均值(左图)或加权平均值 每个国家的人口规模(右图)。 随着时间的推移,无论是水平还是趋势都存在一些明显的差异。

值得注意的是,如果考虑到人口规模,总体水平明显较低,这意味着大国在实现民主方面表现较差。 这也适用于世界多个地区,包括亚太地区、欧洲、拉丁美洲和加勒比地区。 它不适用于前苏联加盟共和国、撒哈拉以南非洲以及中东和北非。 非洲也是唯一一个在这两项措施上都与当代独裁化趋势背道而驰的地区。

这意味着当考虑到人口规模时,专制化的聚集趋势更加明显。 按传统国家平均水平计算的全球民主水平在 2010 年之后略有下降,但完全在置信区间内。 使用人口权重,下降更为明显:按照这一标准,世界已经退回到大约二十五年前苏联解体后的最后一次记录的民主水平。 世界人口的三分之一(25 亿人)生活在当今全球独裁化趋势的国家中。

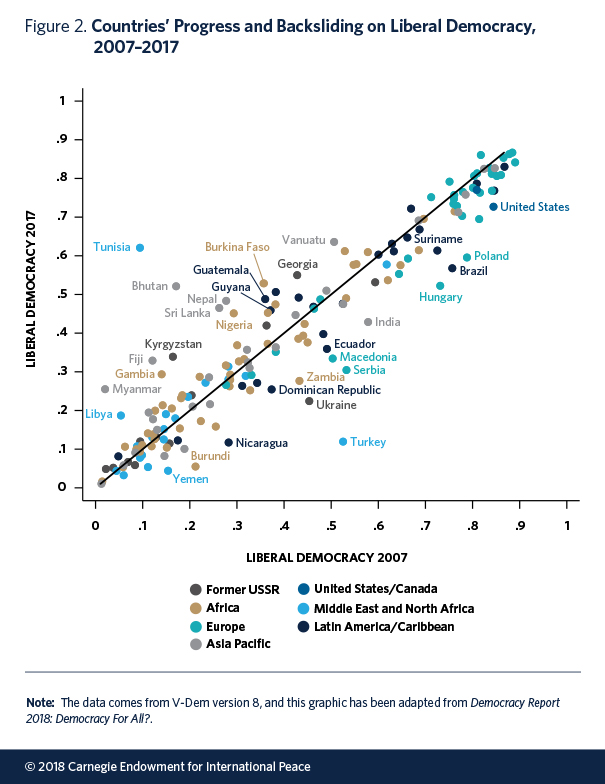

过去十年来,许多国家的民主得分发生了重大变化(见图 2)。1 几个人口大国和国家

1 近年来,一些人口大国的人口数量大幅下降,包括巴西、印度、俄罗斯、土耳其和美国。 值得注意的是,所有这些都是或曾经是民主国家。

虽然也有一些国家在民主方面取得了进展,但它们往往人口较少,例如不丹、布基纳法索、斐济、斯里兰卡或瓦努阿图。 尼日利亚是近十年来唯一一个在自由民主方面取得实质性进展的人口大国。

欧洲的情况

欧洲的民主正在衰落,即使按照更传统的衡量标准也是如此。 当按人口加权时,这一趋势再次更加明显。 按照后一种衡量标准,欧洲的民主水平已经倒退了四十年,回到了 1978 年的水平。这种下降与世界其他几个地区的倒退一样严重。

欧洲经常被描绘成比世界其他地区更先进的民主堡垒,也许除了美国和加拿大之外。 不过,尽管欧洲的平均民主水平仍然位居世界第二,但也仅以微弱优势领先。 当按人口规模加权时,拉丁美洲的民主显然可以与欧洲相媲美。

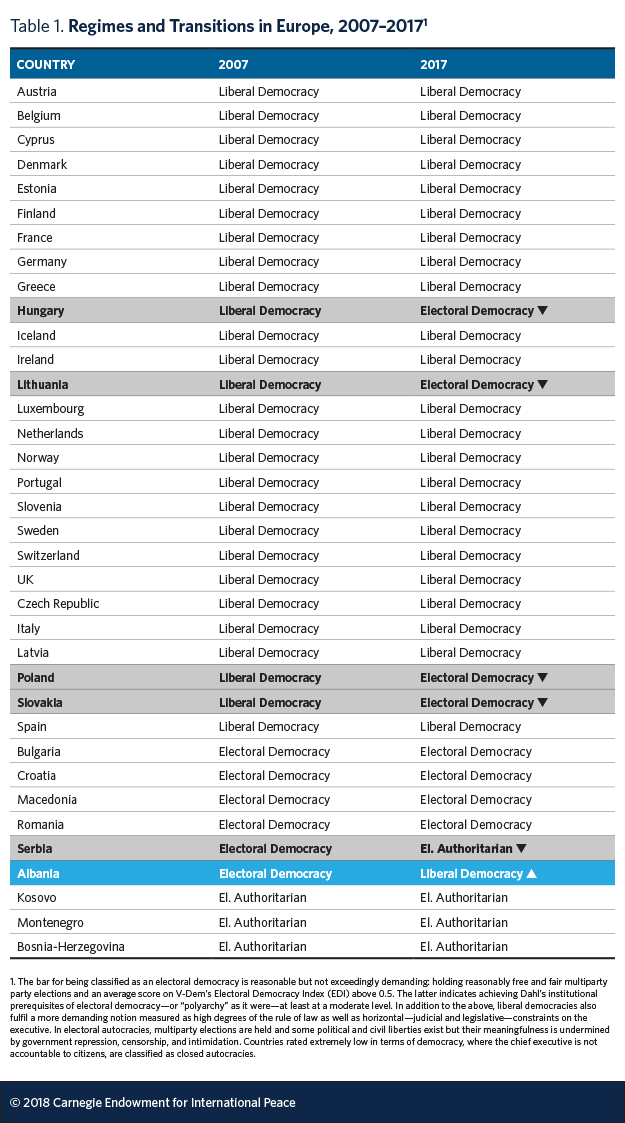

另一个重要的观点是欧洲国家从一种政体向另一种政体的质变,特别是当这种转变跨越民主与专制的鸿沟时(见表1)2。

过去十年来,欧洲的政权分类发生了六次转变。 匈牙利、立陶宛、波兰和斯洛伐克失去了自由民主国家的地位,向下转型为选举民主国家。 其中一些转变已经持续了数年,但波兰的独裁化速度明显加快,华沙的大部分变化发生在 2015 年至 2017 年之间。

幸运的是,迄今为止只发生过一次彻底的民主崩溃。 在塞尔维亚,专制化已经发展到了民主不再受到维护的地步,即使是在最有限的选举意义上也是如此。 在另一个缓慢发展的例子中,政府多年来以渐进的方式改变了其性质,塞尔维亚已成为一个选举独裁国家。

只有阿尔巴尼亚已经过渡到更好的状况,现在有资格成为自由民主国家。

总体而言,证据表明民主正在欧洲失去重要地位。

欧洲正在发生什么变化?

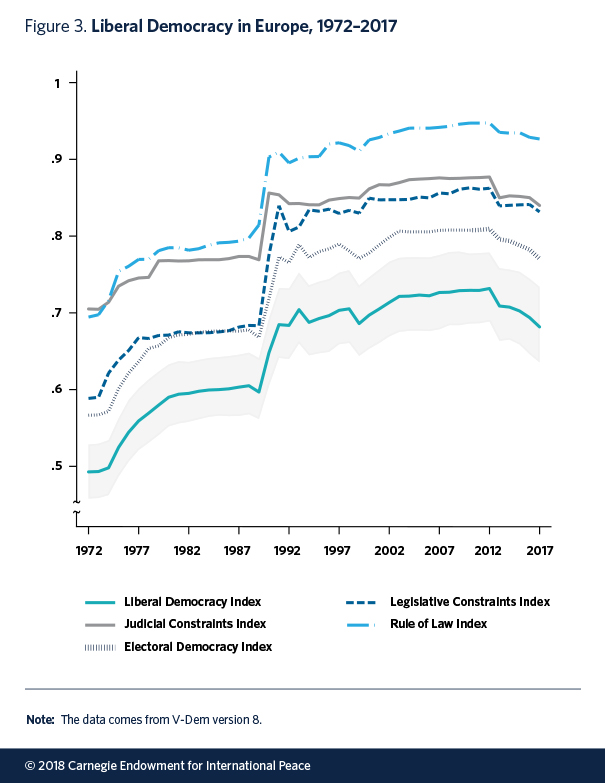

V-Dem 的数据还可以帮助确定民主的哪些方面正在减弱,哪些方面更加牢固。 自由民主指数由选举民主指数和反映更具体的自由主义关切的三个指数组成:法治对公民自由的保护以及对行政机关的司法和立法约束。

近年来推动大部分下降趋势的指数是选举民主指标(见图 3),该指标在各个指数中跌幅最大。

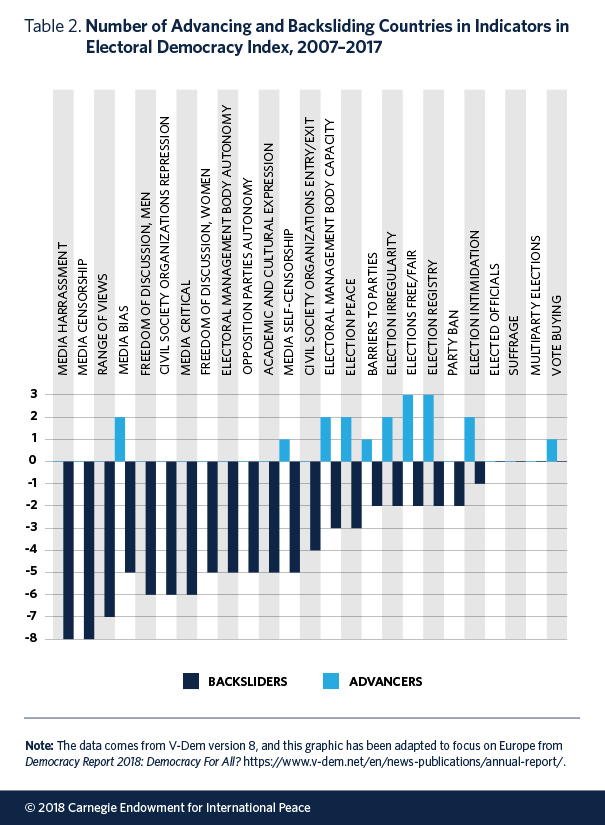

绘制 V-Dem 选举民主指数中的 25 项指标,显示了 2007 年至 2017 年间每项指标显着改善或下降的欧洲国家数量(见表 2)3。

值得注意的是,许多国家衡量言论自由和替代信息来源的指标大幅下降,而只有极少数国家有所改善——只有一个国家的媒体自我审查有所改善,两个国家的媒体对政府的偏见有所减少。 此外,衡量公民社会在不受压制或阻止的情况下自由组织的能力的廉洁选举指数指标也表明民主倒退。

与此同时,干净选举指数中几乎所有纯粹衡量选举方面的指标都显示出改善。 特别是,选举在程序上的自由和公平程度以及选民登记的质量(与选举相关的两个最基本的指标)记录了进步的国家多于下降的国家。

这详细地描绘了当前欧洲民主倒退的趋势。 一些统治精英显然追求不民主,但大多数观察家认为代表民主的选举制度迄今为止一直很健全,甚至有所改善。

相比之下,民主国家却因不太明显的违法行为而倒退。 媒体、学术界、民间社会组织和文化机构的言论自由以及政府和自我审查可能会受到诱导、恐吓和拉拢等相对隐晦的手段的负面影响。 政府逐渐限制自主行为者,削弱他们作为亲民主行为者发挥作用的能力,同时巧妙地提高人们对此类措施的接受程度。 就其本身而言,

就其本身而言,每一步都显得相对无关紧要。 然而,结果加起来现在已经很明显了——如表 2 所示。至关重要的是,这正在削弱那些使选举实践成为重要而有效的民主工具的自由权利和制度。 这是一个有问题的发展,对欧洲民主的未来提出了明确的考验。

欧洲在这方面也不例外。 正如 V-Dem 研究所的《2018 年民主报告》中指出的那样,当今世界各国都存在完全相同的专制化模式。 这不应该成为欧洲的安慰或放松的理由。 相反,在俄罗斯、土耳其和尼加拉瓜等不同国家,媒体、公民社会和言论自由受到破坏和削弱后,随之而来的是更加戏剧化的独裁统治,这令人不舒服地提醒人们注意欧洲的政治动荡。 在20世纪30年代。

结论

欧洲的民主水平仍然接近有记录以来的最高水平。 例如,阿尔巴尼亚最近转变为自由民主国家。 然而,与全球其他地区一样,过去十年的严重独裁化可能会威胁到欧洲民主未来的生存能力。 一些国家最近从自由民主倒退到选举民主,而其他国家则越来越多地出现独裁统治。 这种倒退主要发生在媒体和公民社会——民主的非选举软肋,政府可以在不立即进行审查的情况下限制民主空间。

需要充分理解民主不同组成部分的微妙性和差异,才能正确应对欧洲民主面临的挑战。 选举机构和做法依然强劲(甚至正在改善)。 在许多国家,媒体自由、言论自由、替代信息来源以及法治正在受到破坏。

这些令人不安的结论符合政治学家南希·贝尔梅奥的观察,即“最明目张胆的倒退形式”正在消失,而骚扰反对派和颠覆横向问责制等秘密手段却在增加:“民选高管一一削弱了对行政权力的制约 。 。 。 [并且]阻碍反对派力量挑战行政偏好的力量。”4

同时观察到消极和积极的趋势。 重要的是要认识到欧洲社会的“民主性”正面临压力。 从更广泛的时间来看,当前的形势还没有像之前的危机时刻那么糟糕; 与 20 世纪 70 年代相比,欧洲民主在大多数指标上仍然得分很高。 动荡的时代并不是什么新鲜事。 然而,最近的事态发展无疑给了我们暂停的空间。

V-Dem 的 2017 年民主报告得出的结论是,民主似乎仍然相对有弹性。5 今年的评估更加悲观。 民主正在倒退。 独裁化趋势明显。 与去年最明显的区别是,现在有很多非常强大的国家加入了专制化浪潮,影响了数十亿人,并向世界其他地区发出了非常强烈的信号。

斯塔凡·I·林德伯格 (Staffan I. Lindberg) 是民主多样性 (V-Dem) 研究所所长,也是哥德堡大学政治学教授。

笔记

1 颜色代码按世界各地区划分,仅标记发生显着变化超出置信区间的国家/地区。 这里使用术语“置信区间”来表示贝叶斯最高后验密度将相当于一个标准差的可信区域。 有关 V-Dem 测量模型和置信区间计算的详细信息,请参阅 Daniel Pemstein 等人,“V-Dem 测量模型:跨国家和跨时间专家编码数据的潜在变量分析”,Varieties 哥德堡大学民主研究所,2018 年 4 月,https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/5a/23/5a231d27-8f14-4b87-9a27-1536d6a2e482/v-dem_working_paper_2018_21_3.pdf。

2 Anna Lührmann、Marcus Tannenberg 和 Staffan I. Lindberg,“世界政权 (RoW):为政治政权比较研究开辟新途径”,《政治与治理》6,第 1 期。 1(2018):60-77。

3 橙色条表示在特定指标上倒退的国家数量,而蓝色条则表示前进的国家数量。 这些指标的排序使得位于左侧的国家表示进步的国家多于下降的国家,而表中右侧的国家则相反。

4 南希·贝尔梅奥(Nancy Bermeo),“论民主倒退”,《民主杂志》27,第 1 期。 3(2016):5-19。

5 Anna Lührmann 等人,“黄昏的民主? V-Dem 2017 年年度报告,”民主研究所的多样性,哥德堡大学,2017 年 5 月,https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/91/14/9114ff4a-

Staffan Ingemar Lindberg

生于 1969 年,是瑞典政治学家、民主多样性 (V-Dem) 研究所首席研究员以及哥德堡大学 V-Dem 研究所所长。 瑞典哥德堡大学政治学系教授,瑞典青年科学院院士,瓦伦堡学院院士,政府质量研究所研究员; 奥斯陆分析公司的高级顾问。主要研究比较政治学、民主与民主化、非洲、政治组织、腐败和依附主义。

Staffan I. Lindberg (born 1969), is a Swedish political scientist, Principal Investigator for Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute and Director of the V-Dem Institute[1] at the University of Gothenburg. He is a professor in the Department of Political Science, and member of the Board of University of Gothenburg, Sweden[2] member of the Young Academy of Sweden, Wallenberg Academy Fellow, Research Fellow at the Quality of Government Institute; and senior advisor for the Oslo Analytica.

Lindberg's main research interests are comparative politics,[3] democracy and democratization,[4] Africa, political organizations,[5] corruption[6] and clientelism.

https://www.gu.se/en/about/find-staff/staffanilindberg

Professor Department of Political Science

About Staffan Ingemar Lindberg

Professor, Dept. of Pol. Sci., Univ. of Gothenburg, xlista@gu.se

Founding Director, V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg,

PI, V-Dem Project, Varieties of Democracy, sil@v-dem.net

Wallenberg Academy Fellow 2014-2018 + prolongation 2019-2023

ERC Consolidator Grant, 2017-2022

Background

Staffan I. Lindberg holds a PhD (2005) from Lund University, Sweden. His dissertation won the American Political Science Association's Juan Linz Award for best dissertation 2005. He was assistant professor at Kent State University (2005-2006), assistant/associate professor at University of Florida (2006-2013), and has been with University of Gothenburg since 2010, full professor since 2013.

Interests

Comparative Politics, Democracy and Democratization, Africa, Political Institutions, Public Opinion, Representation, Legislatures, Members of Parliament, Corruption and Clientelism

Editorial/Executive Boards

Chair, Scientific Committe, Infrastructure Grants, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, 2019-present.

Member, Expert Group for Aid Studies, 2019-present.

Member, Editorial Board, Politics and Governance, Democratization, African Journal of Democracy, Journal of Geopolitics, History, and International Relations.

Chair , Scientific Committee, Support to Research Infrastructure, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

Current Research

Lindberg's main current occupation is as Director of the V-Dem Institute at University of Gothenburg and one of four Principal Investigators for Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem). The research infrastructure and the data collection of the V-Dem Institute at University of Gothenburg is now part of the national research infrastructure Demscore which Lindberg also is PI and Director for, supported by financially by Swedish Research Council and the four participating universities (universities of Gothenburg, Uppsala, Stockholm, and Umeå). The research infrastructure at the V-Dem Institute is also supported by the EU (EC/INTPA), Ministry of Foreign Affairs-Sweden, and the Mo Ibrahim Foundation. Previously, support has come from among others, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond, Ministry of Foreign Affairs-DK, CIDA, NORAD, the National Science Foundations of Norway and Denmark, as well as through ERC research grants to Anja Neurndorff/Nottingham University and Carl Henrik Knutsen/University of Oslo.

See also the V-Dem Institute's homepage at University of Gothenburg, and the program V-Dem website. He and his collaborators were awarded the prestigeous "Lijphart/Przeworski/Verba Data Set Award 2016” for best data set in comparative politics. American Political Science Association, Comparative Politics Section.

Lindberg leads several research programs at the V-Dem Institute, including the "Failing and Successful Sequences of Democratisation", Varieties of Autocracy", "Endangered Democracies", and "Case for Democracy" supported by the ERC, K&A Wallenberg Foundation, M&M Wallenberg Foundation, Swedish Research Council, the EU (EC/INTPA), and University of Gothenburg. More information about these research programs can also be found at the V-Dem website.

He is a Wallenberg Academy Scholar, former member of the Young Academy of Sweden & Professor of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, Sweden; holder of an ERC consolidator Grant, and member of several advisory and executive boards, including the expert group for aid studies (EBA) linked to the Swedish government. He has previous served on Board of University of Gothenburg, the executive of APSA's Comparative Politics Section, as Editor and Vice-Chair of the APCG, the co-PI for the research consortium “African Power and Politics” 2007-2009, and has won 40+ grants from both US and in European funders.

His book, Democracy and Elections in Africa (Johns Hopkins UP, 2006) demonstrates the positive causal effect of elections on the spread of democracy. It was awarded "Outstanding Title" by Chocie in 2007. In a collaborative follow-up project, the causal role of elections in processes of both autocratization and democratization were investigated on a global scale. Lindberg is the editor of the resulting volume Democratization by Elections - A New Mode of Transition (Johns Hopkins UP, 2009), as well as co-author of Varieties of Democracy (CUP 2020), Why Democracies Develop and Decline (CUP 2022). His articles on women’s representation, political clientelism, voting behavior, party and electoral systems, democratization, popular attitudes, and the Ghanaian legislature and executive-legislative relationships have appeared in for example AJPS, World Politics, Perspectives on Politics, Journal of Politics, Political Science Quarterly, World Development, Party Politics, European Journal of Political Research, Electoral Studies, Studies in International Comparative Development, Journal of Democracy, International Political Science Review, Political Science Research and Methods, Government and Opposition, Journal of Modern African Studies, and Democratization. Lindberg has worked as election observer several times and been appraiser and reviewer of donors program in several Africa countries.

He has also done in-depth work on Ghana, and has published on political clientelism, voting behavior and party alignment, as well as the workings of the Ghanaian legislature. He taught at Lund University, then Kent State University and University of Florida where he was Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science. He spent two years in Ghana as parliamentary advisor, and consults on a regular basis for donors in Africa.

More information can also be found at:

Public Google Scholar:

http://scholar.google.se/citations?user=aW96DOEAAAAJ

SSRN: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/cf_dev/AbsByAuth.cfm?per_id=864348

?The Nature of Democratic Backsliding in Europe

https://carnegieeurope.eu/2018/07/24/nature-of-democratic-backsliding-in-europe-pub-76868

STAFFAN I. LINDBERG JULY 24, 2018

Summary: European democracy is in decline, as increasingly authoritarian leaders undermine the post–Cold War liberal order by targeting media freedom, individual rights, and the rule of law.

This article is part of the Reshaping European Democracy project, an initiative of Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program and Carnegie Europe.

In Europe, as in most other parts of the world, democracy is retreating and autocracy is gaining. Yet Europe’s challenges are particularly noteworthy. Although it is commonly assumed that democratic backsliding starts with electoral problems, other political elements—such as the infringement of individual rights and the freedom of expression—are at the core of Europe’s democratic woes.

Staffan I. Lindberg

Staffan I. Lindberg is the director of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute and professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg.

The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) index, a signature product of the V-Dem Institute based at the University of Gothenburg, examines the state of global democracy through a distinctive focus on seven different democratic types. V-Dem recently released its 2017 data and annual “Democracy Report 2018,” using over 400 detailed indicators of the particulars of democracy, human rights, civil liberties, and freedoms aggregated from ratings provided by over 3,200 scholars in 180 countries; almost fifty indices capturing components of democracy such as accountability, women’s empowerment, freedom of expression, clean elections, and so on; and five main indices of democracy (electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian democracy) to give new insights into the state of global democracy and the shape of European democracy, in particular.

V-Dem’s data show that a global wave of autocratization—a reduction in democratic qualities that can lead to the breakdown of democracy—is manifesting itself less than thirty years after communism’s collapse and democracy’s global spread generated tremendous hopes for a twenty-first century dominated by liberal democracy. The rise of authoritarianism in Honduras, Nicaragua, Russia, Venezuela, Turkey, and Ukraine, accompanied by substantial backsliding in countries like Brazil, India, Israel, and now the United States, over the past decade testifies to the erroneousness of the optimism expressed in the 1990s. Should the world be genuinely alarmed about the future of democracy in Europe?

A SOBERING GLOBAL PICTURE

The third global wave of democratization started in the mid-1970s and gained momentum across the 1980s and 1990s, peaking between 1993 and 1999. In that period, seventy countries made significant advances on V-Dem’s liberal democracy index every year, while only four to six countries backslid on an annual basis. This dominance of democratic advances over deterioration actually continued from 1978 until around 2010. Since then, a downward trend in democratic progress has become obvious, while the count of nations relapsing has increased. In 2017, the number of countries backsliding matched the count of countries making progress for the first time in forty years.

The overall level of democracy in the world from 1972 to 2017, based on V-Dem’s 2018 data, can be viewed from the perspective of two complementary metrics (see figure 1): conventional averages across countries (the left panel) or averages weighted by each country’s population size (the right panel). There are some noticeable differences, both in levels and the trends over time.

Significantly, overall levels are markedly lower when population size is taken into account, meaning that large countries are worse at delivering democracy. This also holds true for several regions of the world, including the Asia-Pacific, Europe, and Latin America and the Caribbean. It does not hold in the former Soviet republics, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa. Africa is also the only region bucking the contemporary trend of autocratization in both measures.

This means that the gathering trend toward autocratization is much more demonstrable when population sizes are considered. The global level of democracy calculated by conventional country-averages dips slightly after 2010 but is well within confidence intervals. Using population weights, the fall is more pronounced: by this measure, the world has receded to a level of democracy last recorded some twenty-five years ago in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union’s breakup. One-third of the world’s population—2.5 billion people—lives in countries that are now part of the global autocratization trend.

Many countries have experienced major changes in their democracy scores over the last ten years (see figure 2).1 Several large and populous countries have registered substantial declines in recent years, including Brazil, India, Russia, Turkey, and the United States. Notably, all of these are or used to be democracies.

While there are also countries making progress on democracy, they tend to have small populations, such as Bhutan, Burkina Faso, Fiji, Sri Lanka, or Vanuatu. Nigeria is the only country with a large population that has made substantial progress in terms of liberal democracy in the last ten years.

EUROPE’S SITUATION

Democracy in Europe is in decline, even by the more conventional measure. When weighted by population, the trend is again much more apparent. By the latter measure, the level of democracy in Europe has fallen back forty years, to where it was in 1978. This decline is just as steep as the backslide seen in several other regions of the world.

Europe is often portrayed as a bastion of democracy that is more advanced than the rest of the world, perhaps with the exception of the United States and Canada. But while the average level of democracy in Europe is still the second highest in the world, it is only by a slim margin. When weighted for population size, democracy in Latin America is clearly comparable to Europe.

Another important perspective is the qualitative transition from one type of regime to another among European countries, in particular when such transitions cross the democracy-autocracy divide (see table 1).2

Europe has seen six shifts in regime classification over the past ten years. Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovakia lost their status as liberal democracies and transitioned downward to be electoral democracies. Several of these transitions have been drawn out over several years, but the autocratization of Poland is notably picking up speed and most of the changes in Warsaw have occurred between 2015 and 2017.

Fortuitously, only one full democratic breakdown has occurred so far. In Serbia, autocratization has gone so far that democracy is no longer upheld, even in its most limited sense of electoral only. In another instance of slow-moving developments where the government changed its nature in an incremental fashion over many years, Serbia has become an electoral authoritarian state.

Only Albania has transitioned to a better state of affairs, now qualifying as a liberal democracy.

Overall, the evidence points in the direction of democracy losing significant ground in Europe.

WHAT IS CHANGING IN EUROPE?

V-Dem’s data can also help identify which aspects of democracy are diminishing and which are holding up more strongly. The index for liberal democracy consists of the index for electoral democracy and three indices capturing more specific liberal concerns: the protection of civil liberties by the rule of law and both judicial and legislative constraints on the executive.

The index driving most of the downward trend in recent years is the measure of electoral democracy (see figure 3), which has registered the largest drop between the various indices.

Plotting the twenty-five indicators that go into V-Dem’s index of electoral democracy shows the number of countries in Europe that have significantly improved or declined on each indicator between 2007 and 2017 (see table 2).3

Notably, the indicators measuring the freedom of expression and alternative sources of information have declined significantly in many countries while improving in very few—just one country has seen improved media self-censorship and two have seen less media bias in favor of the government. In addition, indicators from the clean elections index that measure civil society’s ability to organize freely without being repressed or prevented from existing also suggest democratic backsliding.

At the same time, almost all indicators that measure purely electoral aspects in the clean elections index show improvement. In particular, the extent to which the elections are free and fair in procedural terms and the quality of the voters’ registry—two of the most fundamental indicators related to elections—record more countries improving than declining.

This gives a detailed depiction of the current trend of democratic backsliding in Europe. Some ruling elites are clearly on an undemocratic quest, but the electoral institutions that most observers think of as representative of democracy have so far been robust or even improving.

In contrast, democracies are backsliding by way of less conspicuous violations. The freedom of expression and government- and self-censorship of the media, academia, civil society organizations, and cultural institutions can be affected negatively by relatively obscure means, such as inducements, intimidations, and co-optation. Incrementally, governments are constraining autonomous actors to impair their abilities to function as pro-democratic actors, while skillfully engineering an increasing level of acceptance for such measures.On its own, each step can appear relatively inconsequential. Yet the outcomes add up and are now evident—as shown in table 2. Critically, this is weakening those liberal rights and institutions that make electoral practices consequential and effective instruments of democracy. This is a problematic development that presents a clear test for the future of democracy in Europe.

Europe is also not exceptional in this regard. As noted in the V-Dem Institute’s “Democracy Report 2018,” the exact same pattern of autocratization is found in countries across the world today. This should not be a comfort to Europe or a reason to relax. On the contrary, the undermining and weakening of media, civil society, and freedom of expression has been followed by more dramatic turns to autocracy in a diverse set of countries including Russia, Turkey, and Nicaragua—and is an uncomfortable reminder of Europe’s political tumult in the 1930s.

CONCLUSION

The level of democracy in Europe remains close to its highest level ever recorded. Albania, for example, recently transitioned into a liberal democracy. Yet, as in other parts of the globe, substantial autocratization over the last ten years may threaten the future viability of democracy in Europe. Several countries have recently backslid from liberal to electoral democracies, and authoritarian rule is increasingly recorded in others. This backsliding occurs primarily in media and civil society—non-electoral soft spots of democracy where governments can limit democratic space with less immediate scrutiny.

The subtlety and variation across different components of democracy needs to be fully understood to correctly address the challenge to democracy in Europe. Electoral institutions and practices remain robust (or are even improving). It is media freedom, freedom of expression and alternative sources of information, and the rule of law that are being undermined in a significant number of countries.

These disquieting conclusions fit political scientist Nancy Bermeo’s observation that “the most blatant forms of backsliding” are disappearing while surreptitious tactics such as harassment of the opposition and subversion of horizontal accountability are on the rise: “Elected executives weaken checks on executive power one by one . . . [and] hamper the power of opposition forces to challenge executive preferences.”4

Both negative and positive trends are observed at the same time. It is important to recognize that the “democraticness” of European society is under strain. Placed in the wider sweep of time, the current situation is not yet as bad as previous moments of crisis; European democracy still scores well across most indicators compared to the 1970s. Tremulous times are nothing new. Yet recent developments most certainly give room for pause.

V-Dem’s 2017 democracy report concluded that democracy still seems relatively resilient.5 This year, the assessment is more pessimistic. Democracy is being rolled back. A trend of autocratization is evident. The starkest difference from last year is the number of very large and powerful nations that are now part of the autocratization wave, affecting billions of people and sending a very strong signal to the rest of the world.

Staffan I. Lindberg is the director of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute and professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg.

NOTES

1 Color codes are by regions of the world, and only countries with significant changes outside of the confidence intervals are labeled. The term “confidence intervals” is used here to denote credible regions in which the Bayesian highest posterior densities would place the equivalent of one standard deviation within. For details on the V-Dem measurement model and the calculation of the confidence intervals, see Daniel Pemstein et al., “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data,” Varieties of Democracy Institute, University of Gothenburg, April 2018, https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/5a/23/5a231d27-8f14-4b87-9a27-1536d6a2e482/v-dem_working_paper_2018_21_3.pdf.

2 Anna Lührmann, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg, “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes,” Politics and Governance 6, no. 1 (2018): 60–77.

3 Orange bars indicate the number of countries that are backsliding on a particular indicator, while blue bars indicate the number of countries advancing. The indicators are ordered so that placement to the left indicates that more countries have improved than have declined, and the reverse is true for those appearing to the right in the table.

4 Nancy Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 3 (2016): 5–19.

5 Anna Lührmann et al., “Democracy at Dusk? V-Dem Annual Report 2017,” Varieties of Democracy Institute, University of Gothenburg, May 2017, https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/91/14/9114ff4a-357e-4296-911a-6bb57bcc6827/v-dem_annualreport2017.pdf; Valeriya Mechkova, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan I. Lindberg, “How Much Backsliding?,” Journal of Democracy 28, no. 4 (2017): 162–69.