《英国卫报》(The Guardian)属英国较为激进的报纸,但质量极高。

此文不是社评,作者John Glaser

也属于激进人士,愤青,自然在美国不是主流。不过话说的中肯,无所谓主流不主流。这是他在《英国卫报》上的专栏:

The problem isn’t China’s rise, but rather America’s insistence on maintaining military and economic dominance right in China’s backyard不代表美国主流,如同奥巴马三番五次强调,“我们美国人就是第一”,更难以被美国媒体大众和精英政要理解。

【参见】

《华尔街日报》U.S. Rebukes China Over Maritime Dispute

此文被广泛引用。《华尔街日报》网文Washington Playing ‘Whack-a-Mole’ in South China Sea, Says Ex-U.S. Official

此文提到的是布莱尔Dennis C. Blair,奥巴马的前任国家情报局主任(Director of National Intelligence),因与奥巴马意见相左而(被迫)辞职。之前布莱尔是美国太平洋战区总司令,也是高层内人。布莱尔反对和中国冲突。

《英国卫报》2015.05.28

The US and China can avoid a collision course – if the US gives up its empire

John Glaser

The problem isn’t China’s rise, but rather America’s insistence on maintaining military and economic dominance right in China’s backyard

To avoid a violent militaristic clash with China, or another cold war rivalry, the United States should pursue a simple solution: give up its empire.

Americans fear that China’s rapid economic growth will slowly translate into a more expansive and assertive foreign policy that will inevitably result in a war with the US. Harvard Professor Graham Allison has found: “in 12 of 16 cases in the past 500 years when a rising power challenged a ruling power, the outcome was war.” Chicago University scholar John Mearsheimer has bluntly argued: “China cannot rise peacefully.”

But the apparently looming conflict between the US and China is not because of China’s rise per se, but rather because the US insists on maintaining military and economic dominance among China’s neighbors. Although Americans like to think of their massive overseas military presence as a benign force that’s inherently stabilizing, Beijing certainly doesn’t see it that way.

According to political scientists Andrew Nathan and Andrew Scobell, Beijing sees America as “the most intrusive outside actor in China’s internal affairs, the guarantor of the status quo in Taiwan, the largest naval presence in the East China and South China seas, [and] the formal or informal military ally of many of China’s neighbors.” (All of which is true.) They think that the US “seeks to curtail China’s political influence and harm China’s interests” with a “militaristic, offense-minded, expansionist, and selfish” foreign policy.

China’s regional ambitions are not uniquely pernicious or aggressive, but they do overlap with America’s ambition to be the dominant power in its own region, and in every region of the world.

Leaving aside caricatured debates about which nation should get to wave the big “Number 1” foam finger, it’s worth asking whether having 50,000 US troops permanently stationed in Japan actually serves US interests and what benefits we derive from keeping almost 30,000 US troops in South Korea and whether Americans will be any safer if the Obama administration manages to reestablish a US military presence in the Philippines to counter China’s maritime territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Many commentators say yes. Robert Kagan argues not only that US hegemony makes us safer and richer, but also that it bestows peace and prosperity on everybody else. If America doesn’t rule, goes his argument, the world becomes less free, less stable and less safe.

But a good chunk of the scholarly literature disputes these claims. “There are good theoretical and empirical reasons”, wrote political scientist Christopher Fettweis in his book Pathologies of Power, “to doubt that US hegemony is the primary cause of the current stability.” The international system, rather than cowering in obedience to American demands for peace, is far more “self-policing”, says Fettweis. A combination of economic development and the destructive power of modern militaries serves as a much more satisfying answer for why states increasingly see war as detrimental to their interests.

International relations theorist Robert Jervis has written that “the pursuit of primacy was what great power politics was all about in the past” but that, in a world of nuclear weapons with “low security threats and great common interests among the developed countries”, primacy does not have the strategic or economic benefits it once had.

Nor does US dominance reap much in the way of tangible rewards for most Americans: international relations theorist Daniel Drezner contends that “the economic benefits from military predominance alone seem, at a minimum, to have been exaggerated”; that “There is little evidence that military primacy yields appreciable geoeconomic gains”; and that, therefore, “an overreliance on military preponderance is badly misguided.”

The struggle for military and economic primacy in Asia is not really about our core national security interests; rather, it’s about preserving status, prestige and America’s neurotic image of itself. Those are pretty dumb reasons to risk war.

There are a host of reasons why the dire predictions of a coming US-China conflict may be wrong, of course. Maybe China’s economy will slow or even suffer crashes. Even if it continues to grow, the US’s economic and military advantage may remain intact for a few more decades, making China’s rise gradual and thus less dangerous.

Moreover, both countries are armed with nuclear weapons. And there’s little reason to think the mutually assured destruction paradigm that characterized the Cold War between the US and the USSR wouldn’t dominate this shift in power as well.

But why take the risk, when maintaining US primacy just isn’t that important to the safety or prosperity of Americans? Knowing that should at least make the idea of giving up empire a little easier.

《华尔街日报》2015.05.27

U.S. Rebukes China Over Maritime Dispute

Defense Secretary Ash Carter says U.S. will ‘fly, sail and operate wherever international law allows’

Gordon Lubold

PEARL HARBOR, Hawaii—China has isolated itself by pursuing development of a chain of artificial islands in the South China Sea, Defense Secretary Ash Carter said, in Washington’s most forceful rebuke yet of Beijing’s attempts to assert its territorial rights in international waters.

“There should be no mistake: the United States will fly, sail and operate wherever international law allows, as we do all around the world,” Mr. Carter said at a ceremony here to recognize a change of commanders at U.S. Pacific Command.

His remarks came a day after China laid out a strategy to shift its armed forces’ focus toward maritime warfare and prevent foreign powers from “meddling” in the South China Sea.

Beijing has defended its actions as legally proper and within the scope of its sovereignty.

The U.S. wants to resolve the international dispute over the islands peacefully, Mr. Carter said, but also wants “an immediate and lasting halt” to land reclamation by China and other claimants, which include the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Taiwan.

“With its actions in the South China Sea, China is out of step with both international norms that underscore the Asia-Pacific’s security architecture,” Mr. Carter said.

The escalating rhetoric over the disputed territory has set the stage for a confrontation between senior Chinese and U.S. officials, including Mr. Carter, at the annual Shangri-La Dialogue, an international security conference, this weekend.

Beijing rejected Mr. Carter’s rebuke.

“China’s determination to safeguard its own sovereignty and territorial integrity is rock-hard and unquestionable. The activities that China carries out are well within the scope of its sovereignty and are beyond reproach, said Zhu Haiquan, a spokesman for the Chinese Embassy in the U.S. “We urge the U.S. side to honor its commitment of not taking sides on issues relating to sovereignty, stop irresponsible and provocative words and deeds, and make no attempts to play up the tension in the region.”

The U.S. defense secretary has sought to persuade Beijing to stop its construction of the islands, which consist of submerged reefs augmented by dredged materials. China has created a total of 2,000 acres of new land mass across seven islands, according to Pentagon officials. About 1,500 acres of those islands were built since January. Satellite images of the expanding land masses show China has built an airstrip on one of the islands that is large enough for fighter jets, transport planes and surveillance aircraft, significantly enhancing Beijing’s capability to patrol the skies in the area.

此图毫无代表性。双方对抗,不可能只局限于上述的武器,中国航母也属于试验舰,无实战能力

While pressing his criticism of Beijing, Mr. Carter hasn’t announced a change in U.S. posture over the islands. Earlier this month, Mr. Carter asked his staff to recommend options to address the issue, including flying aircraft and sailing vessels to within 12 nautical miles of the islands to reassert the right of navigational freedom.

For natural land structures, the 12-nautical mile limit is considered restricted area. Last week, a Navy surveillance plane flew near the islands and was given a warning by Chinese officials to keep back. But the flight didn’t cross the 12-mile threshold, which would have signaled a more dramatic shift in U.S. policy.

Beijing’s determination to expand the islands, which are among a group known as the Spratlys, about 800 miles off mainland China’s shoreline, is bringing the countries of the region together “in new ways” and those countries are demanding more American engagement in the Asia-Pacific, Mr. Carter said at Wednesday’s ceremony. The U.S. has sought to put greater emphasis on the region as part of a rebalancing of strategic focus.

The Philippines contests some of China’s claims in the South China Sea, but lacks modern military equipment needed to defend its maritime territory. Vietnam, another rival claimant, has invested in advanced capabilities such as modern fighter jets, submarines and land-attack cruise missiles, all from Russia. But even after these new weapon systems are in place several years from now, Beijing would enjoy overwhelming superiority in any confrontation with Hanoi.

The same couldn’t be said for a confrontation with the U.S., however.

The People’s Liberation Army has approximately 2,100 fighter or bomber aircraft in its hangars, according to the U.S. Department of Defense. But only a few hundred of those are considered modern aircraft.

China’s only aircraft carrier—while a huge leap forward for its navy—is still seen mainly as a practice platform for a future carrier fleet. A recent Pentagon review of China’s military modernization said Beijing is “investing in capabilities designed to defeat adversary power projection and counter third-party—including U.S.—intervention during a crisis or conflict.” In practice, that means hundreds of ballistic and cruise missiles positioned near the coast to deter Japanese or American warships from coming anywhere near Chinese territory. China has a substantial submarine fleet as well, piling on more risk for enemy ships.

Beijing’s release of the military white paper came with a small courtesy: When President Barack Obama visited China last year, the two countries agreed on some “confidence-building measures” to enhance their relationship. As a result, Beijing notified Washington in advance that it would be releasing the white paper, just as the U.S. told China that the Pentagon would release its own analysis of Chinese military power earlier this month.

《华尔街日报》网文2015.05.28

Washington Playing ‘Whack-a-Mole’ in South China Sea, Says Ex-U.S. Official

Former commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Command, Adm. Dennis Blair, delivers a speech in Tokyo in April

Adm. Dennis Blair, a former head of the U.S. Pacific Command and Director of National Intelligence, accused the U.S. of playing “whack-a-mole” in its approach to China’s island-building in the South China Sea and called for coordinated diplomacy rather than a military response.

“I think that’s terrible,” he said of the string of recent statements from U.S. military officials on the South China Sea tensions. “We shouldn’t be leading with the aircraft carriers down there.”

Adm. Blair, who was asked to resign as Director of National Intelligence in 2010 amid a rift with the White House, has some experience of dealing with China in times of crisis.

He was U.S. Pacific Command chief in 2001 when a Chinese fighter jet collided with a U.S. spy plane, killing the Chinese pilot and forcing the U.S. aircraft to make an emergency landing on China’s southern island of Hainan. China detained the crew for 11 days.

In an interview on the sidelines of an energy conference in Beijing on Thursday, Adm. Blair said he had privately advised the U.S. government to encourage other claimants in the South China Sea to negotiate a multilateral compromise that took into account China’s position — whether or not Beijing participated in those talks. China has maintained that territorial disputes should be resolved through bilateral negotiation between the parties involved, rather than through multilateral talks.

He said the main problem would be the Spratly Islands, where China holds eight rocks and reefs and other claimants occupy dozens of islands and other features.

“The only thing I can think of there is you divide them up: Okay, Philippines you get 20, Malaysia gets 15, China gets 10,” he said of a hypothetical solution. He added that any deal would have to include “certain rules,” such as a ban on military forces and an agreement to jointly develop fishing and other resources.

The U.S. and its allies would likely back such a deal, he said.

“So then we can put whatever civilian or military actions we want to take into some sort of overall context, rather than flying an airplane here, running an aircraft carrier there, having a Shangri-La declaration there,” he said, referring to an annual regional security forum set to take place in Singapore this weekend.

“Right now we’re just playing whack-a-mole.”

He noted that some senior State Department officials had also made public statements on the issues, but added: “They’ve been counter-punching and they’ve been defensive rather than saying this is how we want the place to look like.”

Nonetheless, Adm. Blair said there is little China’s forces could do in the Spratlys to deter what the U.S. sees as free navigation in international waters.

“The Spratlys are 900 miles away from China, for God’s sake. Those things have no ability to defend themselves in any sort of military sense,” said Adm. Blair, who today serves as a director at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

He is also chairman of the Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA, an independent non-profit institution that seeks to enhance understanding of U.S.-Japan relations.

“If the Chinese were ever so foolish as to try to take any sort of actual military action from those islands, they’re completely indefensible militarily. Heck, the Philippines and the Vietnamese could put them out of action, much less us,” he said.

2015.05.05

我国实现T800高强度碳纤维量产 性能超日本东丽

【此文登载网站用黑色背景,没法读,像是脑残。文章风格属中国老一套,宣传部的,没劲】

用小小的纤维体来做自行车钢铁支架?没错,碳纤维的“小身板”中就蕴涵着这样的大能量。不仅如此,它还在航天工业、国防军工等领域大显身手,被誉为工业界的“黑色黄金”。

然而,由于长期以来我国高性能碳纤维研发和产业化水平落后,加上国外的技术封锁和产品禁运,相关材料需求常常陷于“无米之炊”的境地。

在此背景下,江苏航科复合材料科技有限公司(以下简称航科)打出自主创新牌,生产出全球领先的T800碳纤维,率先突破国际高技术垄断,开创了我国高技术装备制造材料产业化新格局。

昔日之殇,今日之志

近日,德国宝马公司新上市的i3电动车,用直径仅有0.007毫米的碳纤维材料代替传统钢铁制造车身,使高科技产品再次夺人眼球。

“高性能碳纤维不仅质量轻,而且强度可以达到超高强度钢材的13~20倍,同时还具有极佳的耐腐蚀等特点,是国防尖端技术和改造传统产业的基础原材料。”航科总经理王浩静在接受《中国科学报》记者采访时说。

一代材料,一代装备。王浩静对此深有感触。由于碳纤维在航空航天等国防工业中有重要用途,西方国家将其视为战略性物资,对中国“禁运”,更不转让技术、不出售设备。

回忆往昔,两院资深院士师昌绪仍记得,1984年,上海碳素厂试图引进美国特科公司碳化设备,最终被美国国防部否决;1990年,吉林化学工业公司经过谈判、考察,最终购买了一些碳化设备及相应测试仪器,但经多次试车,碳化炉始终开不起来。

“新材料中碳纤维是重中之重,我国却一直难以有大的突破,特别是不匀率高、毛丝多,力学性能也上不去,和国外产品质量差距越拉越大,无法制备航空航天结构材料。”师昌绪在接受《中国科学报》记者采访时说。

“国外已经实现了碳纤维高性能化、低成本化和系列化,其制备和应用技术已颇为成熟,如民用客机B787和A350,复合材料用量已经达到50%以上。而我国不能制造高性能碳纤维,导致几乎所有的高技术装备无法实现其设计性能。”王浩静对比说。

他介绍说,当前全球高性能碳纤维生产技术仍主要集中在日本东丽、美国赫氏、德国西格里集团等少量企业手中,其成本平均只有传统碳纤维材料的一半左右,占据着全球过半市场。

同时,据《研究与市场》最新发布的《2018年全球碳纤维市场增长机遇与预测》报告,未来5年,除了传统应用大户航空业以外,受风力发电、离心机转子管、电子工业等潜在应用市场的驱动,全球碳纤维市场成交额有望以每年两位数的增长率递增。

“发展碳纤维技术和产业是我们的强国必由之路,影响到高端制造业、民生和国家的安全。”师昌绪说。实现强国梦,当前的面貌必须要改变,必须重视新材料的研发、产业化与应用。

昔日之殇成为全体航科人的最大动力。为了急国家之急,2010年2月,中科院西安光学精密机械研究所和江苏镇江市政府签署战略合作协议,成立航科公司,试图探索出一条高新技术产业化和产业报国的新路子,实现高性能碳纤维自主创新发展。

披荆斩棘,唱响世界

“创业三年来,上过当,受过骗,遇过挫折,公司从一片泥土地发展到现在花园式的厂房,实现T800碳纤维产品技术突破与产业化,终于风雨之后见彩虹。”谈起创业历程,王浩静笑言。

创业就意味着披荆斩棘。新材料研发往往是多领域高新技术的集成,碳纤维也不例外,它涉及到高分子聚合、纺织、传动、热工等多领域学科交叉。而国内相关基础研究薄弱,没有系统的标准,配套技术也几乎都属于原创,一切都要从头做起,研究难度可想而知。

“特别糟糕的是一些企业宣传上不负责任,搞得天花乱坠,使传统体系的研发‘成果’和颠覆性新技术碰撞、厮杀,导致我们做大量的解释工作和验证工作,造成时间和优势力量的极大浪费。”王浩静回忆说。

尽管困难重重,但王浩静从未言弃。二十多年来的研究经验和取得的系列创新性成果给了他“底气”。为了早日生产出T800碳纤维,所有技术团队每天工作18小时,夜以继日地讨论方案,航科当年获得了中国首届创新创业大赛奖一等奖。

同时,功夫不负有心人。在西安光机所赵卫所长、武文斌书记以及镇江高新技术开发区李小平书记等领导支持下,江苏航科创造了中国碳纤维研发和产业化速度。

2012年,公司成立仅两年,航科就投资2.5亿元建设的国内首条T800生产线实现了稳定批量生产,打破了发达国家对高性能碳纤维研制与生产的关键设备与技术瓶颈的封锁和垄断,填补了国内高性能碳纤维制造的空白。

“航科T800碳纤维最大特点是可以根据用户需要进行表面处理和上浆,完全以用户为中心进行配套生产。”王浩静介绍说。同时,航科已具备系列化高性能碳纤维制备技术和低成本化能力,碳纤维生产原材料和主要设备几乎100%来自国内。

截至目前,航科先后申请国家发明和实用新型专利80余个,制定碳纤维生产流程测试规范42项,环保节能措施使产品成本降低30%,产品性能离散型低于5%,T800碳纤维性能达到甚至超过了日本东丽公司水平。

面对成果,王浩静淡然而言:“成功的经验谈不上,我们的理念是‘态度决定一切,细节决定成败’。不计个人得失,只为报效祖国!”

创新为帜,再攀高峰

作为21世纪的新材料,很多人把碳纤维看成是“改变全球现存游戏格局”的潜力股。

对此,王浩静表示,尽管我国碳纤维生产较国外发展慢,但消费量与日俱增,市场需求旺盛。“未来5年,国际市场发展可能会远远低于国内的发展,可能会是13%与130%的差异,所以在中国碳纤维材料一定是个潜力股。”王浩静信心满满地说。

目前,航科已全面启动千吨级T800碳纤维生产线的建设工作,计划2015年全面投产。公司同时具备T700、T800和MJ系列碳纤维的供货能力。预计到2020年,将建成千吨级T1000碳纤维生产线和百吨级MJ系列碳纤维生产线,并开展T1200和M70J等更高性能纤维以及专用复合材料的研制及产业化工作。

同时,航科已经掌握了制约碳纤维发展的关键技术和设备瓶颈,实现了从工艺到设备,从性能到质量,从人员到管理等方面的快速提升。计划在未来10年内打造成我国碳纤维高技术成果转化基地、领域人才培养基地和碳纤维产业化示范基地。

“做文章、做专利不是科研的最终目标,科研的最终目标在于以最大的价值回报社会。科研人员走出去做企业,可以激发他们的激情,最大限度地释放他们的科研潜力和能力水平。”西光所运营与产业发展出处长曹慧涛在接受本报记者采访时说。他表示西光所将继续为航科未来发展提供技术和智力支持。据了解,目前,西光所已建成近30家技术创新型企业。

面对未来,王浩静和他的“兵”们将继续沿着创新之路,推进我国碳纤维研发生产,并走向国际市场。他们将争取发挥每个人的创造性、积极性和团队作战的统一性与协调性,侧重发展管理制度的实用性,让所有职工对公司具有自豪感和危机感。

我们有理由相信,未来江苏航科一定会独树一帜,屹立在世界碳纤维之林,为国家、地方经济发展发挥更大的力量。

2015.03.05

装备技术薄弱 “新材料之王”呼唤中国研发能力

装备技术薄弱,产品成本偏高,技术开发相对落后……全国30多家企业碳纤维总产能不及日本一家企业。

“新材料之王”呼唤中国研发能力

碳纤维被称为“新材料之王”,对支撑我国制造业转型升级、保障国防安全等具有重要作用。然而,记者近日从有关碳纤维产业发展论坛上获悉,我国碳纤维产业近年来虽取得长足进步,但受制于研发能力低下、质量参差不齐等问题,我国企业在国际碳纤维市场上话语权微弱,处于市场垄断地位的美、日等发达国家企业占尽优势。与会企业界人士和专家学者急切呼吁:加大对碳纤维行业的引导和扶持力度刻不容缓。

中国碳纤维产量仅占全球3.2%

“由于采用了碳纤维零部件,宝马i3的重量比世界上最畅销的电动汽车日产聆风还轻20%。”“不只是汽车行业,目前,碳纤维在各领域的应用都开始出现井喷现象,整个产业链的技术进步与降低成本,是中国这个产业成败的关键……”

1月下旬,吉林化纤集团承办的“吉林省碳纤维产业技术创新战略联盟会员大会暨碳纤维产业发展论坛”在吉林市召开,与会的200余名企业界人士和专家学者,几乎占据了中国碳纤维应用及开发领域半壁江山。看得出,他们每个人脸上都写满急切的表情。

据了解,碳纤维密度低、强度大,质量比铝轻,强度却高于钢铁,但又具备纺织纤维的柔软可加工性,可谓“外柔内刚”,且耐腐蚀、耐高温、耐疲劳,耐冲击性能好,兼之热膨胀系数小,拥有良好的导电导热性能及电磁屏蔽性,因此被称为“新材料之王”。

“2014年全球碳纤维总产量约为10万吨,主要被日、美企业所垄断,我国实际产量只有3200吨左右。”中国化学纤维工业协会副会长赵向东预计,2015年国内碳纤维需求量将达到1.5万吨。

由于现有产量远不能满足需求,仅去年上半年,我国碳纤维及制品的进口量便达到5513.2吨。而未来中国四大产业——大飞机项目、海上风力发电、汽车轻量化发展及高速铁路,无疑还将带动碳纤维需求的强势增长。

“如果国内碳纤维产业不抓紧时间迎头赶上,未来中国几大工业恐很难不受制于人。”与会人士焦急地说。

技术薄弱、生产成本高

“装备技术薄弱、产品质量稳定性有待提高、应用技术开发相对落后等,都是制约中国碳纤维产业发展的瓶颈。”赵向东直言不讳。

关于碳纤维技术,国外一直在对我国进行严格封锁。20世纪60年代,中国开始自行研究,不过,我国主要产品的性能和国际先进水平仍存在差距。

为实现“抱团”发展,2014年6月,吉林化纤集团发起成立了吉林省碳纤维产业技术创新战略联盟,我国30多家碳纤维企业中,有23家是该联盟成员,此外还有10家高校与科研院所。

据悉,依托联盟提供的平台,吉林省东风化工有限责任公司生产的碳纤维电热防寒马甲,已为环卫工人配发试穿,碳纤维电热地板产品也已完成试制;吉林西科碳纤维技术开发公司承接了北车集团高铁所需的碳纤维复合材料技术开发工作……

吉林化纤董事长宋德武指出,联盟的工作虽取得了一定成绩,但各成员单位间的技术封闭仍有待进一步打开,企业原始创新和技术成果转化的脚步尚需加快。

据悉,生产成本偏高,是我国很多企业的共性问题。这也导致尽管市场需求在不断加大,但目前吉林省碳纤维产业联盟内企业还没有实现全部满负荷生产。

“眼下中国碳纤维企业规模还太小,全国30多家企业的总产能,都不及日本东丽一家,难以与业内国际巨头竞争。”东华大学教授余木火表示。

未来重点是产业规模和产业链问题

当前,不少国家都在积极布局,着力发展碳纤维产业,将其作为抢占下一轮工业和国防竞争制高点的重要支撑。以汽车行业为例,据长安汽车设计院院长曹渡介绍,碳纤维材料在车身上的应用,可大大减轻车重,而车重每减10%,便可降低6%~8%的油耗,降低5~6%的排放,并有助于提升车辆的加速与制动性能。为此,日本计划未来5年投资20亿日元,支持碳纤维原材料企业和汽车主机厂的合作,而美国能源部今明两年将为同类项目提供2175万美元的资金支持。

“如果说福特创建流水线生产是汽车行业的第一次革命,那么碳纤维+新能源可能是第二次汽车革命。作为全球汽车产销第一大国,中国必须把握汽车未来发展的趋势,若中国品牌汽车没有提早布局,有可能再次被甩飞。”曹渡神情急迫。

据了解,为发展碳纤维产业,支撑我国制造业转型升级,2013年,工信部制定了《加快推进碳纤维行业发展行动计划》,2014年8月,中国碳纤维及复合材料产业发展联盟也在北京成立。

“受制于研发能力低下、质量参差不齐等问题,我国企业在国际碳纤维市场上话语权微弱,让一些国际碳纤维产业巨头占尽优势。”在当天论坛上,不少业内人士认为,中国仍需不断加大对碳纤维行业的引导和扶持力度。

“没有规模不成为产业,未来重点是产业规模和产业链问题。”余木火教授指出,面对碳纤维广阔的应用前景,应该发挥国家意志,培养一批产业链企业,每个环节培育1~2家龙头企业,并与科研院所共同建立中国研发能力,支撑产业的跨越式发展。

2014.12.19

影响中国碳纤维产业发展的关键因素

本文由中国石墨业协会副秘书长刘荣华推荐

碳纤维是一种性能优异的战略性新材料,近年来,我国碳纤维产业化进程快速推进,成为少数几个可以生产碳纤维的国家。但是发达国家重点企业垄断了全球市场并实现了产业化,相比之下我国碳纤维产业仍然存在较大差距。总结先进国家的成功经验,找到影响我国碳纤维行业产业发展的关键因素,是行业突破的前提条件。

我国碳纤维行业整体处于起步阶段,关键技术装备以及产品稳定性与发达国家还存在一定差距。对碳纤维行业进行深入研究,发现影响产业发展的关键因素,总结先进国家的成功经验,提出适合我国碳纤维行业的发展思路和政策建议,有助于行业实现突破,对于保障国家重大工程以及国防科工的发展有着重要的战略意义。

一、从战略高度看待碳纤维业发展

碳纤维是一种性能优异的战略性新材料,密度不到钢的1/4、强度是钢的5-7倍,并且具有耐高温、耐腐蚀、热膨胀系数小等特点,广泛应用于航空航天、能源装备、交通运输、体育休闲等领域。碳纤维行业发展需要集成化工、纺织、冶金、材料、装备等多领域的技术和工艺,可以有效带动传统产业和下游产业的转型升级。碳纤维行业的发展水平可以体现一个国家的工业基础、研发实力和管理水平。

(一)战略性新兴产业发展的基础

碳纤维是为了满足军事领域对隔热、耐烧蚀、轻质高强材料的需求而开发的,是典型的军民两用材料,在航空航天、卫星导弹、武器装备等领域有广泛的应用,可以满足先进武器装备对材料性能指标的要求,在实现武器轻量化和节能化方面有着重要的作用。如美国B1、B2、F22、F117等隐型战机大量使用碳纤维材料;国产战斗机、神州飞船也需要高性能碳纤维复合材料制备的关键结构件。碳纤维是国防现代化建设不可或缺的关键材料之一。

按《新材料“十二五”发展规划》统计,“十二五”期间,我国风电新增装机6000万千瓦以上,新能源汽车累计产销量将超过50万辆,大型客机等航空航天装备的复合材料应用比重将大幅增加。碳纤维复合材料的应用是风电大型化、轻量化的必然趋势,是新能源汽车实现减重、提高行驶里程的关键,可以大幅提高大型客机的燃油经济性。另外,碳纤维在压力容器、建筑补强、输电电缆、高铁设备等工业领域有很好的应用前景。

碳纤维行业的发展不仅能够满足国民经济和重大工程对高性能材料的需求,还可以推动石化化工、纺织化纤等传统行业的技术进步和转型升级,带动下游的航空航天、机械设备、能源交通等行业的发展,可以推动上下游产业的技术进步,形成上下游产业相互促进、互相推动的格局。碳纤维及其复合材料的应用,可以提高设备、装备的安全性,实现轻量化,提高燃油的经济性,减少有毒有害气体排放。

(二)日美企业产量占全球八成以上

1974年,日本东丽公司开始生产T300级和M40级碳纤维,之后美、英、德等国也相继掌握了生产技术。碳纤维早期主要用于航空航天和导弹等军事装备。随着碳纤维性能不断提升和低成本化的发展,在工业领域的应用逐步占据主导地位。

2011年,全球聚丙烯腈基碳纤维产能约9.8万吨,产量约6万吨,保持了年均约18%的增长速度。日本的产能占世界57%,美国占24%。世界生产PAN基碳纤维的重点企业约10家,日本东丽、东邦、三菱、美国赫氏、卓尔泰克、氰特是碳纤维主要生产企业,产量占世界80%以上,其中日本东丽公司处于世界领先地位,独家垄断高端碳纤维市场。2011年全球碳纤维消费量超过5万吨,其中工业应用约占60%,包括压力容器、汽车部件、风电、电子材料和石油、天然气设备等,其次航空航天约占20%,体育休闲器材约占20%。

从发展趋势看,随着碳纤维趋于高性能化,加之成本和价格不断下降,民用工业用量将继续保持快速增长,航天航空和体育休闲用量将稳定增加。据行业预测,到2015年,世界碳纤维产能将达到15万吨/年,产量约9.5万吨,消费量约8万吨。跨国公司将不断扩大产能,巩固其垄断地位,到2015年,日本东丽计划将产能从目前的1.9万吨/年增至2.7万吨/年。新兴国家的很多企业也不断进入碳纤维领域,如土耳其阿克萨、印度凯马奥思凯、韩国晓星、泰光和沙特沙比克等公司都加大了碳纤维产业的投资。

(三)我国产业链初步建立

长期以来,日、美等发达国家在碳纤维高端产品、技术装备等方面对我国进行封锁或限制性管理。自上世纪60年代以来,我国对碳纤维技术进行了积极的探索,但产业化进程十分缓慢。进入新世纪以来,我国碳纤维行业取得了一系列重大突破,打破了国外的技术封锁,建立了国产化主流技术,初步建立起技术研发、工程化研究和产业化生产的行业格局。特别是近年来,建立了国家级的研发平台,工程化技术日益成熟,千吨级工业化装置陆续建成并投产,初步建立了从原丝、碳纤维到复合材料及下游制品全产业链,为加快产业发展奠定了较好的基础。

2012年,我国碳纤维产能约1.2万吨,在建产能约6300吨,产量约2550吨,开工率约22%,表观消费量约1万吨,进口碳纤维约8600吨。我国碳纤维应用以体育休闲为主,约占60%,航空航天和工业领域的应用占比较低。我国碳纤维生产企业约26家,分布在14个省区市,江苏、吉林、辽宁比较集中。其中,具有千吨级(以12K计)规模的企业有4家,分别是山东威海拓展、中复神鹰、江苏恒神和中国化工。从资本构成看,碳纤维生产企业既包括央企和上市公司,又包括民企和股份公司等。从企业原来从事行业看,既包括与碳纤维生产技术密切相关的石化、化纤、纺织机械,又包括煤化工、工程塑料、冶金等。从技术来源看,碳纤维企业各具特色,包括:中石油吉化长期以自主研发为主;江苏恒神以引进为主,既引进国外先进的设备,又注重从国内外引进人才;中国化工收购英国Courtaulds公司,部分引进原丝技术;常州中简、河南永煤和中科院扬州中心的技术来自于中科院山西煤化所,浙江先泰的生产技术来自于中科院宁波材料所,北京化工大学同样是行业重要的技术支撑力量。

二、碳纤维行业发展四大特征

碳纤维技术研发周期长,对稳定性要求很高。碳纤维属于技术密集行业,研发周期长,技术壁垒高,需要集成高分子化学、纺丝工艺、高温冶金、精细化工、复合材料等方面的理论技术和工艺装备,产业链条非常长,关键控制点超过3000多个,同时对稳定性有非常苛刻的要求,既要求同时生产的每根、每束性能保持一致,又要求随着生产周期的延长,性能要保持稳定。在碳纤维发展史上,东丽花了5年的时间专门研发原丝,用了10年时间不断稳定提升T300碳纤维的性能,1984年研发成功T800碳纤维,近年来才开始大规模生产。

重点企业垄断全球市场并实现了产业化。美国注重原始创新,日本擅长精细化生产,在碳纤维产业发展中各具优势。复杂的工艺流程、高昂的研发费用以及很长的研发周期,使得国际上真正具有研发和生产能力的公司屈指可数。日本东丽公司独家垄断高端碳纤维市场,但其他重点企业也各具特色,在原料多元化、合成体系、纺丝技术、丝束规格等方面具备各自的比较优势。比如,美国氰特除了可以生产PAN基碳纤维外,还可以生产高性能沥青基碳纤维;美国卓克泰尔在更具前景的大丝束PAN基碳纤维方面,产能处于领先地位;中国台湾台塑技术水平普通,但通过提高效率降低成本等手段,借助自身在塑料领域的优势,迅速扩张;土耳其阿什卡与陶氏合作,充分利用其在油剂、上浆剂、树脂、复合材料领域的技术优势,为未来发展奠定基础。

应用领域不断拓展,潜在市场逐步成熟。碳纤维下游应用技术的开发难度较高,碳纤维、树脂、上浆剂等之间工艺参数必须系统配合,复合材料设计与成型需要一体化,下游领域的应用开发需要较长的研发过程。同时,重点企业垄断市场,通过国防科工和航空航天等高端市场就可以获得巨额利润,缺乏降低价格扩大应用市场的动力。加之研发投入高、生产成本高,碳纤维应用范围长期局限在一些高端领域。近年来,随着碳纤维应用成本的下降,应用领域逐步由航空航天、体育休闲等扩展到一般工业领域,风力发电、压力容器、交通运输、输电电缆等领域的应用逐步成熟。为了应对这种趋势,东丽公司将成本更低的干喷湿法T700级碳纤维作为发展重点之一,收购了美国卓克泰尔,进入了成本更低的大丝束碳纤维领域,扩大单线产能规模以降低成本,建设了公共研发平台,不断加强与下游企业的合作研发。

市场和政府在行业发展中发挥了重要作用。碳纤维属于军民两用、政治敏感的战略性新材料,其早期开发具有浓厚的国家意志。时至今日,俄罗斯依然沿用前苏联模式,国家主导研发和生产,国有部门负责开发研究生产制造,保障国防科工和重大工程的需求。美国和日本采取以市场为主的模式,主要依靠大企业研发和生产,同时供应民用和国防应用领域。但是碳纤维天然与国防军工密不可分,企业的背后始终存在国家的影子。日本通过各种途径支持本国碳纤维企业发展,将其作为十大战略性产业之一。美国规定国防军工所需的重要材料都必须立足于本国生产,波音可以用东丽的碳纤维,国防军工则采用本国赫氏或氰特的碳纤维,同时对碳纤维高端产品和技术装备出口严格管控。

三、加速中国碳纤维行业发展

(一)基本思路

全球碳纤维市场的基本特征是寡头垄断,与自由竞争的市场经济有很大区别,同时其技术密集、军民两用、政治敏感的特征,使得企业行为的背后始终伴随着国家意志。作为发展中国家,我国碳纤维企业研发实力薄弱,资金资本积累不足,单纯依靠市场和企业自身的力量,很难突破国际巨头的垄断。另外,从发展中国家的成功经验来看,日本和韩国实现现代化的过程中,许多产业都经历了政府大力推动的过程,之后随着现代化的深入,政府又逐步转移经济主导权。但是政府主导行业发展的模式并不可取,计划经济的内在缺陷使企业对市场发展形势不敏感,缺乏持续创新适应市场的内在动力和基础,缺乏持续造血的能力。

我国碳纤维行业发展迅速,但仍有较大差距。近年来,我国碳纤维产业化进程快速推进,成为少数几个可以生产碳纤维的国家。但是,与发达国家相比,我国碳纤维产业仍然存在较大差距,主要表现为:

一是产业化水平有待提高,关键工艺技术还须完善,原辅料及装备水平落后,综合的工艺技术集成能力存在差距。高强中模和高模碳纤维还没有实现产业化,恒张力收丝装置、高温碳化炉、石墨化炉等大型关键设备不能自主制造,进口成本高并受到一定程度的限制。

二是国内部分企业经营困难,普遍存在开工率低、产量小、质量不稳定、成本高等问题,同时根据国内行业发展情况,国际大企业不断降低出口我国市场的碳纤维价格,国内生产企业面临很大竞争压力。

三是低水平重复建设较严重,产业集中度低,全球重点企业仅有10家,而我国已建、在建的碳纤维企业就有约26家,并且多数企业采用东丽工艺路线,没有实现差异化发展,多数建设的是T300级碳纤维生产线,而大丝束聚丙烯腈基碳纤维和高性能沥青基碳纤维仍然处于空白。

四是产学研用缺乏密切的协作,企业的技术实力弱。上下游企业缺乏深度合作,应用产品标准和设计规范滞后,应用市场亟须培育和开拓。多头管理体制,资金投入强度不足,使用分散。

我国碳纤维产业发展必须坚持“政府引导、市场主导”的发展模式,政府对重大科技攻关事项等进行引导,集中力量攻克关键共性技术,同时尊重市场经济和高科技产业发展的基本规律,发挥市场配置资源的基础性作用,产业化和市场化交由企业自主决策、自主实施。

(二)加大政策资金支持力度

切实落实《加快推进碳纤维行业发展行动计划》的要求,发挥国家专项资金和重大工程的牵引作用,集中力量突破关键共性工艺和装备,重视新技术、新工艺、新应用的研究开发,形成技术突破和核心专利。制定和完善基于国内产品的产品标准和工程设计规范,建设公共检测和服务平台,打通上下游产业链的关键环节。抑制低水平重复建设,规范市场秩序,推动要素向优势企业和高端项目集中,增强行业和企业的可持续发展能力。

(三)增强企业全产业链竞争优势

碳纤维生产企业不仅要注重提高产品本身的质量性能,同时要高度重视高端装备、专用化学品、高性能树脂以及复合材料设计开发等方面的发展,积极与下游企业联合设计开发产品,主动帮助下游企业发现需求,积极拓宽应用领域,发展量大面广的产品,带动提升质量性能,降低成本,发展高端产品满足重大工程和国防科工的需求,走军民融合的发展道路。根据自身比较优势,提高产业化竞争能力,逐步由提供产品向提供综合性解决方案转变,不断增强全产业链的竞争优势。

(四)加强产学研用合作,提高以企业为主体的创新能力

推动高校、科研院所与企业加强合作,充分利用互补资源,攻克解决生产技术难题,形成技术突破和专利,提高科研成果和专利技术的转化效率,建立以企业为主体的创新体系。为高校和科研机构的科技人才参与企业技术创新活动创造条件,联合培养既精通技术又熟悉行业形势的高端复合型人才,不断壮大企业高层次创新队伍。

(五)推动成立产业联盟,加强运行监测和风险预警

组织重点上下游企业和研发机构,推动成立碳纤维产业联盟,配合政府加强宏观调控,密切关注国内外的发展态势和竞争情况,及时发布行业最新态势,实现信息在行业内共享和交流,引导行业发展。推动企业间的加强合作和资源整合,打造完整的产业链条,推进与国际的交流与合作。(来源:石墨邦)

2015.04.10

由碳纤维产业链看中国碳纤维突围之道

从碳纤维产业链来看,我国碳纤维领域上市企业有:原丝生产商奇峰化纤,原丝碳化企业中钢吉炭和金发科技,碳纤维预浸料和复合材料生产企业大元股份和航天复合材料企业博云新材。据美国AJR 顾问公司预测,碳纤维丝束的全球销售额将由2011 年的16 亿美元增长至2020 年的45 亿美元,碳纤维增强复合材料的销售额将从2011 年的161.1 亿美元增长到2020 年的487 亿美元。碳纤维的市场前景被全球材料界普遍看好,每一步的发展都备受瞩目。然而,我国碳纤维上市公司几乎全部亏损,新材料之王的光环正在消退。是什么原因导致了我国碳纤维企业现在的困境?我国碳纤维产业又面临哪些挑战,存在什么问题?应该采取什么样的突围方式?本文对此进行了研究,以期帮助我国碳纤维企业突出重围。

一、碳纤维产业链

碳纤维是含碳量在90%以上的无机高分子纤维,具有高强度、高模量、耐高温、耐腐蚀、耐摩擦、导热和导电等多种优异的性能。碳纤维是国民经济和国防建设不可或缺的战略性新材料,在航空航天、汽车工业、风力发电、油田钻探、碳纤维复合芯电缆、建筑补强、文体休闲和医疗器械等方面具有广泛的应用。碳纤维产业链主要包括原丝、碳纤维、中间材料、复合材料和下游应用五个环节。

碳纤维的应用领域主要是航空航天、工业应用和体育休闲三大块。从全球来看,碳纤维在一般工业应用需求占比达61%,航空航天约为22%,体育休闲仅17%。碳纤维国际市场被日、美企业所垄断,近几年,土耳其、韩国和沙特和我国等新兴国家碳纤维产业正在崛起。

二、我国碳纤维产业面临挑战和存在问题

(一)面临挑战

由于碳纤维复合材料应用领域的特殊性,国外对高性能碳纤维技术与高端工艺装备实施垄断封锁,低端碳纤维产品向我国倾销。日本等国外大型企业占据全球95%以上碳纤维市场,并利用其技术和规模优势压低价格,导致国内企业被迫降价。我国稳定生产一个级别的碳纤维后,国外企业的价格就大幅下降一次。例如,2010年12k的T300产品价格为24万元/吨,2012年则下降到12万元/吨。受国外低价倾销和恶意竞销的影响,加上我国碳纤维企业小而散的状态,质量尚不太稳定,而且生产成本高于进口同类产品价格,全行业呈亏损状态。

上游碳纤维价格大的波动,对下游复合材料企业成本影响很大,制约了我国碳纤维复合材料产业的健康发展。此外,随着土耳其、韩国、俄罗斯、印度和沙特等国家碳纤维项目的陆续投产,并且随着国内碳纤维产能的逐步释放,碳纤维市场竞争将更加残酷。

(二)存在问题

我国碳纤维行业存在自主创新能力不强、关键技术落后、复合材料产业薄弱和市场应用开发滞后等问题。碳纤维行业研发、生产与应用相互脱节,产业链不畅通是制约我国碳纤维行业健康发展的一大瓶颈。

1、上游碳纤维缺乏核心技术

近年来,我国碳纤维企业由10家迅速膨胀到30家,低水平重复建设现象普遍,产业集中度低,无法与国际碳纤维企业巨头相抗衡。上游碳纤维企业片面强调规模扩张,而忽视技术研发,尚未形成关键技术协同攻关、工艺问题共同突破的合作机制。碳纤维技术被日本、美国等专利覆盖,我国企业缺乏核心自主知识产权的技术支撑,尚未全面掌握完整的碳纤维核心关键技术。

原丝是生产碳纤维的关键,而我国原丝水平落后,绝大多数碳纤维企业采用的是二甲基亚砜原丝技术,质量尚未过关,其他原丝技术发展相对滞后,加剧了技术同质化的低效竞争。我国碳纤维性能不高、产品稳定性差、生产成本居高不下,高性能纤维一些关键问题还没有完全突破。此外,碳纤维设备生产技术几乎被国外垄断,且严格限制对我国出口。而我国机械制造业落后,碳化炉等关键设备研发滞后。国产碳化炉发热体所使用的碳化硅最高耐受温度仅为1400℃,不能达到大尺寸碳化炉的工艺要求。因此,提高碳纤维企业的技术水平是当务之急。

2、中游复合材料产业薄弱

无论是在技术水平还是产量方面,与国际先进水平相比,我国碳纤维复合材料都存在一定差距。日本、德国、美国等少数发达国家掌握了每平方米70克至75克标准的碳纤维预浸料生产技术,而我国还不能生产每平方米低于80克的碳纤维预浸料,高端碳纤维预浸料主要依靠进口。我国碳纤维预浸料年需求量达7000万平方米左右,其中4000万平方米依靠进口。碳纤维复合材料的树脂材料以及后端的加工和设备,则完全由美国公司垄断。我国高性能复合材料整体上尚处于起步阶段,层合固化工艺及装备还相当落后,很多先进的设备还必须依赖进口,制约了我国碳纤维复合材料的发展。

3、下游市场需求疲软

碳纤维复合材料应用对国产碳纤维的牵引效应不足,特别是工业领域用碳纤维需求不足,这严重制约了我国碳纤维产业的发展规模和质量。当前世界发达国家的碳纤维在航空航天、工业应用和体育休闲应用占比分别为15%、65%和20%,我国碳纤维应用目前仍集中在相对低端的体育休闲产业,航空航天、工业应用和体育休闲用品分别占比为5%、35%和60%。我国从事碳纤维复合材料制品研制和生产,以及设备制造的厂家有百余家。其中大多是生产体育休闲用品,原因在于这些领域对碳纤维的性能要求不高,不需要长时间的材料认证和成品实验,门槛较低。而从事航空航天等高端碳纤维复合材料研制和生产单位仅10余家,从事纤维缠绕和拉挤成型工艺生产碳纤维复合材料的企业40余家。

三、我国碳纤维突围之道

我国碳纤维产业发展正处于关键时期,面对国外行业巨头的打压,应积极探索适合自身发展的道路。通过实施市场保护制度,加强碳纤维生产企业间以及上下游企业间和科研单位之间的联系与合作,推进研发、生产、应用一体化,以碳纤维应用带动上游发展,推动我国碳纤维产业持续健康发展。

(一)实施市场保护制度

作为战略性新兴产业,碳纤维产业不应该与成熟产业保持相同的开放程度。将其纳入开放的国际环境中,国外优势企业产品的大量涌入制约了我国碳纤维产业的发展。我国享受在一些发展水平较低的战略性部门实施一定的贸易保护的特权,因此,要积极制定战略性新兴产业市场保护制度。在我国碳纤维产业发展水平不高,也不具备世界竞争力的情况下,面对国外行业巨头的打压,通过实施市场保护制度推动碳纤维等战略性新兴产业的发展。

(二)促进产业链协调发展

国外碳纤维生产企业与航空航天、汽车工业等碳纤维应用企业建立了良好的合作关系,建立了完整的碳纤维产业链。例如,日本碳纤维企业与美国波音公司和法国空客公司合作,在波音B787和空客A380飞机上大量使用碳纤维复合材料。上游原丝直接影响碳纤维的质量和成本,下游应用需求将推动碳纤维的发展,因此,要从整个产业链的角度来发展碳纤维产业,提高自主创新能力和开发能力,形成大型企业集团,构筑从原丝、碳纤维、中间材料至复合材料的全套产业链,以实现利润最大化。

1、积极培育碳纤维生产

建立市场导向的技术创新机制,围绕航空航天、汽车工业、医疗器械、体育休闲等重点领域。加大技术创新扶持力度,突破和掌握关键核心共性技术,促进技术成果产业化。一是建立以企业为主体,高等院校和科研院所共同参与的创新体系,不断提高企业自主创新意识,并把建设创新型产业作为战略目标;二是突破制约碳纤维产业发展的关键技术和设备瓶颈。提高碳纤维原丝生产技术,发展两种或两种以上的碳纤维原丝制备工艺,形成多元化技术体系,为生产高性能碳纤维提供保证。积极研发高低温碳化炉等关键设备,降低生产成本,提高产业化水平;三是加强与国外交流,寻找与国外发达国家合作的突破口,促进我国碳纤维产业持续健康发展;四是加强人才引进和科技合作,以多种形式吸引国内外人才,为行业健康发展提供支撑。

2、壮大复合材料产业

立足于服务碳纤维,开发出适合我国碳纤维的预浸料,并以预浸料带动碳纤维的销售。积极开发碳纤维复合材料低成本制备技术,例如RTM/RFI工艺,自动铺放技术,纤维缠绕、拉挤成形,电子束固化等复合材料低成本制造工艺技术。开展复合材料制造技术先进化,材料高性能化、多功能化和应用扩大化研究。针对碳纤维在国防军工和航空航天等领域对高性能碳纤维复合材料的要求,重视热压罐、自动铺带机/铺丝机等成形应用设备的技术研发。此外,积极培育具有竞争力的骨干企业,鼓励以大型复合材料生产企业为龙头,开展跨地区、跨所有制的联合重组,培育若干产业集聚区,提高行业竞争力。

3、开拓下游应用领域

碳纤维复合材料在大型飞机、风力发电叶片、汽车部件、石油开采抽油杆、电力输送电缆等领域的应用将推动节能减排的实现,但是由于碳纤维及其复合材料的生产成本较高而限制了其使用范围。因此,应通过积极降低成本来开拓和培育下游应用市场。

针对碳纤维及其复合材料在大飞机制造、航天工程、国防军工等高端领域应用,积极发展高性能碳纤维及其复合材料;瞄准工业领域这个巨大的市场,着力发展通用级碳纤维产品,并通过降低成本和提升产品性能来增强自身的竞争力,推进其在工业领域的应用;体育用品是碳纤维长期需求的领域,面对普通体育用品等低价产品市场的竞争激烈,应不断提高产品品质。在国民经济重点领域形成巨大的碳纤维复合材料市场,建立起完整的碳纤维及其复合材料产业链。

2015.04.03

中国碳纤维产业突破:技术是"弯道提速"的强大引擎

【赛迪网讯】近日,全球首部3D打印电动车“Strati”在美国芝加哥2014年国际制造科技大展(IMTS)亮相。这部用碳纤维材料打造的3D打印电动汽车,从打印到组装完成仅需5天时间,时速可达约80公里,此款电动汽车在通过安全测试后还可实现高速公路行驶。至此,碳纤维材料再一次夯实了其在新材料应用领域中的地位。碳纤维凭借着轻质、高强、耐高温、抗腐蚀等特点,被用于航空、导弹等国防军工领域,同时又在风力发电、汽车零部件、压缩气瓶等民用领域应用广泛,技术附加值和政治敏感型很高,极具战略价值,一度被称为“新材料之王”。当今的国内外碳纤维产业,国外企业领跑地位突出,技术领先优势明显,而中国碳纤维企业发展相对缓慢,与国外企业相比存在较大差距。

在工信部2013年10月发布的《加快推进碳纤维行业发展行动计划》中提出,目前我国碳纤维行业存在的主要问题是:与国际先进水平相比,我国碳纤维行业技术创新能力弱、工艺装备不完善、产品性能不稳定、生产成本高、低水平重复建设、高端品种产业化水平低、标准化建设滞后、下游应用开发严重不足等诸多问题。一方面,由于日美企业对其生产的高性能碳纤维严格限制对华出口,通用及碳纤维成套技术出口须出口国政府特批,因此,我国高性能碳纤维长期依赖进口,碳纤维行业供需缺口达70%。另一方面,我国低端碳纤维产品扩张盲目,已出现了产能过剩的局面,高端产品研发能力不足,使我国碳纤维企业盈利能力受阻。突破高端技术是缩小国际差距的重要途径,也是我国碳纤维产业发展的关键。

在技术突破上,要想实现弯道提速,就要借鉴发达国家经验。日本是全球最大的碳纤维生产国,自上世纪50年代就掌握了碳纤维的生产方法,60年代开始生产低模量聚丙烯腈基碳纤维,80年代便成功研制出高强高模T800、T1000等高性能碳纤维。日本在高性能碳纤维领域发展迅速,得益于政府政策的有力推动,也得益于其产业联盟模式和人才培养方式。政府在政策上给予了大量人力和经费支持,使日本碳纤维行业得以更有效地集中各方资源解决共性问题;日本碳纤维产业联盟成立较早,成员覆盖了整个碳纤维产业链,通过制定上下游合作的产品质量标准,实现了实现纤维产业低成本和高质量的技术突破;在人才培养方面,以东丽(Toray)为例,全产业链的研发人员规模均衡,重视复合型人才培养,其研发团队人员稳定,核心人员服务时间可达20年之久,并在主导发明的同时传代新人。

在政策、产业联盟和人才培养三方面,我国碳纤维产业做的如何呢?

在政策上,近年来工信部及各地方政府积极发布了多项专门针对碳纤维行业发展的政策,在人才培养、资金扶持、技术推进等多方面支持行业发展,2013年底T800级碳纤维研发生产获中央财政八千万元支持,2014年初,我国即实现了T800高强度碳纤维的技术突破,政策支持卓显成效。

2010年我国成立了“碳纤维及其复合材料产业技术创新战略联盟”,发展至今已有18家会员企业,企业间建立了长期的战略合作关系。2014年初,科技部批准成立了“中国碳纤维及复合材料产业发展联盟”。联盟涵盖了碳纤维上下游企业和科研院所共计42家,联盟的重点工作是技术攻关,重点解决T300级等中低端碳纤维产品的批次稳定性和成本控制问题,加快T700、T800级等中高端纤维产品的产业化,同时,碳纤维产业联盟成员之间要加强沟通合作,打破体制机制的束缚,深化军民融合,引导优势民营企业进入军品科研生产领域。

我国科研院所和企业多年来注重人才培养和高端人才引进,例如在吉林等多个碳纤维企业集中的区域多次提出人才引进与培养工作方案,但科技人才多集中于科研院所,高端人才仍处于紧缺的局面,这一现象在专利申请上尤为明显。截至2012年已成功申请专利8154个,占世界专利总量的16.2%,但远低于日本、美国等技术发达国家。专利申请人以国内高校为主,企业研发实力薄弱。另一方面,高端人才对企业的忠诚度有待加强。我国市场机制灵活,企业人才流动速度很快,企业需要寻找合适的人才激励方式才能有效减少人才流失。

从以上三方面可以看出,我国虽然技术起点薄弱,但借助成熟企业的发展经验,加上我国在研发机构数量和规模、人才团队等优势,研发技术已有了突破性的进展,但多项举措仍处于实施阶段。从日美等拥有高端技术国家的发展历程和经验推断,中国碳纤维产业的发展需以市场为导向、产学研结合为抓手、政策支持为保障,加快授权专利由高校和科研机构向企业流动的过程,根据产业链特点和产品发展阶段合理布局技术专利和人才投资,鼓励外资来华投资,引进国外已有先进技术,快速实现高端碳纤维材料进口向碳纤维技术引进的转变,从而实现弯道提速,快速追赶国际先进企业的发展步伐。

《The Atlantic》

Why the U.S. Needs to Listen to China

And why China needs to listen to the U.S. The importance of the mutual economic criticisms between two major world powers

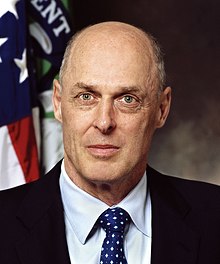

Henry M. Paulson Jr. and Robert E. Rubin

The relationship between the United States and China involves cooperation and competition, but recently the latter has received more attention. Much of the mistrust between the two countries has its roots in geopolitical tensions—China’s assertive behavior in the East and South China Seas, for instance, or U.S. naval surveillance off China’s coasts. But economic tensions have played a large role as well.

Discussions of the U.S.-China economic relationship too often begin with a recital of each country’s grievances against the other. The usual litany of American criticisms includes China’s management of its exchange rate, subsidies that benefit state-owned enterprises, and barriers to American companies seeking to operate in China. Another prominent critique involves Chinese cyber-hacking of U.S. businesses’ intellectual property, and China’s failure to protect intellectual property more generally.

For its part, China castigates the U.S. for its irresponsible fiscal trajectory, its political opposition to Chinese investment in American companies and infrastructure, and its export-control laws, especially those restricting the export of technologies with potential military applications.

We believe it’s time to turn the typical exchange of economic critiques on its head. The two countries have largely been engaged in a dialogue of the deaf, each blaming the other for its own failings, exerting pressure on the other to accede to its demands, and too often waiting for the other to act first. In fact, it is in each country’s self-interest to meaningfully address the criticisms made by the other.

The greatest American threat to China’s economic future is the possibility that America’s economic success could come to an end; the greatest economic danger China poses to the U.S. is the chance that China’s economy fails to grow. By contrast, if each country gets its own house in order and thus succeeds economically, that should diminish economic insecurity, which generates friction, and increase confidence about the future, which fosters a constructive relationship. As former U.S. Treasury secretaries with long experience working with China, we believe each country should undertake significant reforms. Seriously considering each other’s criticisms is a good way to begin.

The united states has enormous long-term strengths, including a dynamic and entrepreneurial culture, a strong rule of law, flexible labor and capital markets, vast natural resources, and relatively favorable age demographics. But China is right to say that improving America’s long-term fiscal outlook is a prerequisite to sustainable growth. Well-structured fiscal reforms could contribute to growth and job creation now while reducing the burden of debt in the future. Some argue that the government could create jobs and increase demand in the short term through public investment in infrastructure or other sectors, while simultaneously taking steps to improve the country’s long-term fiscal trajectory. Others argue that the nation could create more well-paying jobs by reforming its tax code for individuals and corporations, reducing the distortions that undermine economic competitiveness while raising necessary revenue.

Chinese investors could help the United States speed growth now without worsening its long-term debt problem. The U.S. has vast infrastructure needs and a paucity of public capital. But byzantine regulatory and policy barriers too often discourage private investment in major projects. A more streamlined and welcoming environment for domestic and foreign investment in infrastructure projects would create jobs and boost competitiveness.

Much of the effort to attract Chinese investment—whether in infrastructure or manufacturing or agribusiness—needs to come from outside Washington. States and cities have a choice: they can continue to be passive recipients of occasional Chinese investment, or they can design more-systematic approaches to seeking Chinese capital, and the jobs and competitive advantages that accompany it. In Ohio, Michigan, and California, for example, proactive governors are attracting Chinese investment and creating high-quality jobs in sectors like auto parts and clean energy.

Chinese investment could also benefit the U.S. by facilitating exports back to China. In the industrial Midwest, for example, relatively small firms, including family businesses, play a large role in manufacturing and employment. Expansion into China could contribute to the growth of many of these firms. Chinese investors not only can inject capital into these firms; they can help them navigate Chinese markets through strategic partnerships.

Relaxing some export controls is another way to expand opportunities for U.S. firms—and address a common Chinese critique of U.S. economic policy in the bargain. The U.S. should of course restrict the export of technologies with military applications when the national-security implications are significant. But many so-called dual-use products—those with important nonmilitary applications and some military applications—are restricted unnecessarily, and this harms the workers who make those products. In some areas, such as clean energy, the U.S. can both increase exports and promote other national interests—like helping China meet environmental goals and climate-related commitments.

Just as the United States should act on Chinese criticisms, China would be better off taking American criticisms seriously. For sustained economic growth, China must de-emphasize government investment in its own infrastructure, which currently plays an outsize role in the economy, and enable private investment in services and other emerging sectors. And it must de-emphasize exports in favor of domestic-led growth, especially household consumption. These shifts can be advanced by opening the economy further to private-sector competition, including competition from U.S. companies. Doing that would force state-owned firms to compete on a level playing field, without preferential treatment, and give a boost to both the private sector—the future of the Chinese economy—and the underdeveloped service sector. The Bilateral Investment Treaty with the U.S., currently being negotiated, would help by giving Chinese reformers leverage to open their markets to competition and encourage cross-border investment, creating jobs in both countries.

Chinese investors could help the U.S. speed growth without worsening its debt problem.

The efficiency of China’s economy would likewise improve if the country reformed its financial sector, encouraging competition (and empowering Chinese consumers) by granting more private banking licenses, liberalizing interest rates on deposits, and ending preferential access to credit for state-owned firms. Those subsidies create an overabundance of cheap money that many Chinese companies depend upon. Mispriced capital impedes the evolution of China’s economy, prevents the efficient use of capital, and financially constrains some of the economy’s best performers—private companies, which are already responsible for more than 70 percent of Chinese jobs.

China also subsidizes land, energy, and resource prices, in part to support its massive industrial sector. These subsidies are a major reason China is now the dominant global player in steel, cement, and other industries, but they have also distorted the Chinese economy. Beijing has begun to liberalize many commodity prices and has pledged to make further adjustments, including to oil and natural-gas prices. China has its own motivations for doing this—for example, to conserve resources and encourage efficiency. Continued movement toward market pricing would allocate resources more rationally and improve the workings of the Chinese economy, while also eliminating a major source of economic tension between Washington and Beijing. Similarly, there have long been tensions regarding China’s use of artificially low exchange rates to subsidize exports, but currency reform is manifestly in China’s own interest. Its leadership understands this and has made real progress here.

Finally, China’s long-term success, and even much of its near-term success, depends on innovation, as its leaders have said. Innovation, in turn, requires the protection of intellectual property. China has made many commitments to protect intellectual property in the past, but too often ignores them. Ultimately, that will hurt domestic companies such as Xiaomi and Alibaba more than it will hurt Apple or Amazon. China and the U.S. would also benefit from a global regime to protect intellectual property from hacking for commercial purposes.

By addressing each other’s chief economic criticisms, China and the U.S. would simultaneously improve their own economies, remove irritants to their relationship, and foster trust. Doing so would not make geopolitical tensions disappear, but it would anchor them in a framework of mutual interest.

For all their differences, the U.S. and China face several similar internal challenges: rising health-care costs, inadequately funded social safety nets, and fiscal problems at the state or municipal level. And each faces serious income-distribution issues, though the specifics are different. The U.S. continues to face significant pressure on low- and middle-income wages, as well as widening income disparity, which runs contrary to the nation’s objective of broadly shared growth. In China, the emergence of an ultra-wealthy class is stoking resentment and unease.

The two countries also share an important external challenge: the need for a smoothly working global trading regime. As the world’s largest trading nations, they both have an interest in heading off protectionism that would damage their economies. And beyond trade, the two countries have other common goals: Middle East stability, especially with regard to Islamic extremism; climate-change mitigation; nuclear nonproliferation.

It will be much easier to make progress on these issues if America is working in complementary ways with China than if the two countries are working at cross-purposes. The international institutions that should be dealing with these challenges are far from adequate. But if the United States and China—the world’s two biggest economies—act together, that can create the kind of political and moral suasion that helps lead global action. The recent bilateral climate agreement, pledging to limit emissions in both countries, demonstrates how U.S.-China cooperation can produce meaningful results.

Arguably, the best hope for effective transnational action on many of the world’s thorniest problems lies in the cooperation of these two countries. For that to happen, perhaps the most crucial challenge will be to first look within.

举国之力发展自主操作系统?

中国在关键技术还是很薄弱,许多关键

中国制造2025”顶级领导机构即将组建

2015.06.04

中国工程院院士倪光南:发展中国自主操作系统应倾举国之力

近期,网上一则非洲最流行的手机来自中国的消息,引发网友热议。虽则如此,中国工程院院士倪光南还是表达了担忧,国产手机做的非常出色,但有一个巨大的软肋,那就是缺乏一个自主可控的移动操作系统。昨晚在出席国产化操作系统及其产业在国防科技领域的应用论坛时,他还强调,发展中国自主操作系统应倾举国之力,发扬两弹一星和载人航天精神。

对于国产手机的持续火爆,倪光南认为,虽然国产手机做的非常出色,但有一个巨大的软肋,那就是缺乏一个自主可控的移动操作系统,同时他还解释,智能终端操作系统具有高度的垄断性,而目前这块被谷歌、微软和苹果三家垄断。

对于中国自主操作系统,倪光南表示,要解决技术受制于人的问题,应着眼国家安全和长远发展,召集有关部门和单位积极制定信息核心技术设备的战略规划。目前国内从事操作系统开发的有十几家企业,各自为战,不能形成合力;对知识产权风险未作充分评估。

中国工程院院士倪光南

面对如此状况,倪光南强调,发展中国自主操作系统应倾举国之力,应当发扬两弹一星和载人航天精神。加大自主创新力度,发挥我国能集中力量办大事的优势,倾举国之力实现智能终端自主操作系统从无到有的突破。

此外,倪光南还认为很多企业在安卓上做定制,既是低水平重复,又做不到自主可控。中国智能终端操作系统产业联盟正是在这种背景下成立的。联盟接受中央网络安全和信息化领导小组办公室与工业和信息化部的指导,目前已有以中国电科集团为首、包括“产学研用”各界的百余个成员单位,通过整合资源,协同创新,积极推进包括移动操作系统和桌面操作系统在内的中国智能终端操作系统的发展。

倪光南最后还强调,操作系统是信息领域生态系统的核心,操作系统提供者可以轻易地获取用户的许多敏感信息。在大数据时代,数以亿计的用户信息很容易被分析处理,无论是个人层面还是国家层面,可以说没有任何秘密可言。

联邦调查局反恐记

有线电视(CNN)的报道:

Authorities: Three men attempted to join ISIS, had ambitious plans

法庭记录

The Sting

How the FBI Created a Terrorist

By Trevor Aaronson 03/16/2015

IN THE VIDEO, Sami Osmakac is tall and gaunt, with jutting cheekbones and a scraggly beard. He sits cross-legged on the maroon carpet of the hotel room, wearing white cotton socks and pants that rise up his legs to reveal his thin, pale ankles. An AK-47 leans against the closet door behind him. What appears to be a suicide vest is strapped to his body. In his right hand is a pistol.

“Recording,” says an unseen man behind the camera.

“This video is to all the Muslim youth and to all the Muslims worldwide,” Osmakac says, looking straight into the lens. “This is a call to the truth. It is the call to help and aid in the party of Allah … and pay him back for every sister that has been raped and every brother that has been tortured and raped.”

osmakac-martyrdom

Osmakac in his “martyrdom video.” (YouTube)

The recording goes on for about eight minutes. Osmakac says he’ll avenge the deaths of Muslims in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and elsewhere. He refers to Americans as kuffar, an Arabic term for nonbelievers. “Eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth,” he says. “Woman for a woman, child for a child.”

Osmakac was 25 years old on January 7, 2012, when he filmed what the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice would later call a “martyrdom video.” He was also broke and struggling with mental illness.

After recording this video in a rundown Days Inn in Tampa, Florida, Osmakac prepared to deliver what he thought was a car bomb to a popular Irish bar. According to the government, Osmakac was a dangerous, lone-wolf terrorist who would have bombed the Tampa bar, then headed to a local casino where he would have taken hostages, before finally detonating his suicide vest once police arrived.

But if Osmakac was a terrorist, he was only one in his troubled mind and in the minds of ambitious federal agents. The government could not provide any evidence that he had connections to international terrorists. He didn’t have his own weapons. He didn’t even have enough money to replace the dead battery in his beat-up, green 1994 Honda Accord.

Osmakac was the target of an elaborately orchestrated FBI sting that involved a paid informant, as well as FBI agents and support staff working on the setup for more than three months. The FBI provided all of the weapons seen in Osmakac’s martyrdom video. The bureau also gave Osmakac the car bomb he allegedly planned to detonate, and even money for a taxi so he could get to where the FBI needed him to go. Osmakac was a deeply disturbed young man, according to several of the psychiatrists and psychologists who examined him before trial. He became a “terrorist” only after the FBI provided the means, opportunity and final prodding necessary to make him one.

Since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the FBI has arrested dozens of young men like Osmakac in controversial counterterrorism stings. One recent case involved a rudderless 20-year-old in Cincinnati, Ohio, named Christopher Cornell, who conspired with an FBI informant — seeking “favorable treatment” for his own “criminal exposure” — in a harebrained plot to build pipe bombs and attack Capitol Hill. And just last month, on February 25, the FBI arrested and charged two Brooklyn men for plotting, with the aid of a paid informant, to travel to Syria and join the Islamic State. The likelihood that the men would have stepped foot in Syria of their own accord seems low; only after they met the informant, who helped with travel applications and other hurdles, did their planning take shape.

Informant-led sting operations are central to the FBI’s counterterrorism program. Of 08 defendants prosecuted in federal terrorism-related cases in the decade after 9/11, 243 were involved with an FBI informant, while 158 were the targets of sting operations. Of those cases, an informant or FBI undercover operative led 49 defendants in their terrorism plots, similar to the way Osmakac was led in his.

In these cases, the FBI says paid informants and undercover agents are foiling attacks before they occur. But the evidence suggests — and a recent Human Rights Watch report on the subject illustrates — that the FBI isn’t always nabbing would-be terrorists so much as setting up mentally ill or economically desperate people to commit crimes they could never have accomplished on their own.

At least in Osmakac’s case, FBI agents seem to agree with that criticism, though they never intended for that admission to become public. In the Osmakac sting, the undercover FBI agent went by the pseudonym “Amir Jones.” He’s the guy behind the camera in Osmakac’s martyrdom video. Amir, posing as a dealer who could provide weapons, wore a hidden recording device throughout the sting.

The device picked up conversations, including, apparently, back at the FBI’s Tampa Field Office, a gated compound beneath the flight path of Tampa International Airport, among agents and employees who assumed their words were private and protected. These unintentional recordings offer an exclusive look inside an FBI counterterrorism sting, and suggest that, even in the eyes of the FBI agents involved, these sting targets aren’t always the threatening figures they are made out to be.

ON JANUARY 7, 2012, after the martyrdom video was recorded, Amir and others poked fun at Osmakac and the little movie the FBI had helped him produce.

“When he was putting stuff on, he acted like he was nervous,” one of the speakers tells Amir. “He kept backing away …”

“Yeah,” Amir agrees.

“He looked nervous on the camera,” someone else adds.

“Yeah, he got excited. I think he got excited when he saw the stuff,” Amir says, referring to the weapons that were laid out on the hotel bed.

“Oh, yeah, you could tell,” yet another person chimes in. “He was all like, like a, like a six-year-old in a toy store.”

In other recorded conservations, Richard Worms, the FBI squad supervisor, describes Osmakac as a “retarded fool” who doesn’t have “a pot to piss in.” The agents talk about the prosecutors’ eagerness for a “Hollywood ending” for their sting. They refer to Osmakac’s targets as “wishy-washy,” and his terrorist ambitions as a “pipe-dream scenario.” The transcripts show FBI agents struggled to put $500 in Osmakac’s hands so he could make a down payment on the weapons — something the Justice Department insisted on to demonstrate Osmakac’s capacity for and commitment to terrorism.

“The money represents he’s willing to do it, because if we can’t show him killing, we can show him giving money,” FBI Special Agent Taylor Reed explains in one conversation.

These transcripts were never supposed to be revealed in their entirety. The government argued that their release could harm the U.S. government by revealing “law enforcement investigative strategy and methods.” U.S. Magistrate Judge Anthony E. Porcelli not only sealed the transcripts, but also placed them under a protective order.

The files, provided by a confidential source to The Intercept in partnership with the Investigative Fund, provide a rare behind-the-scenes account of an FBI counterterrorism sting, revealing how federal agents leveraged their relationship with a paid informant and plotted for months to turn the hapless Sami Osmakac into a terrorist. Neither the FBI Tampa Field Office nor FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C. responded to requests from The Intercept for comment on the Osmakac case or the remarks made by FBI agents and employees about the sting.

Osmakac as a boy. (Photo courtesy of the Osmakac family)

SAMI OSMAKAC WAS 13 years old when he came to the United States with his family. Fleeing violence in Kosovo in 1992, they had first traveled to Germany, where they stayed until 2000, when they were granted entrance to the U.S. He was the youngest of eight children, and he and his older brother Avni struggled at first to adapt to a new land, a new language and a new culture.

“We came to Tampa, and at first we lived in this really bad neighborhood,” Avni recalls, wearing blue jeans, spotless white Nikes and a white New York Yankees Starter cap. “It was tough, but as we learned the language, things got easier. We adapted.”

The Osmakac family opened a popular bakery in St. Petersburg, across the bay from Tampa. They were Muslim, but they rarely attended the mosque. They didn’t usually fast during Ramadan, and Sami’s sisters did not cover their hair. Growing up, Sami wasn’t particularly drawn to Islam either, according to his family. He suffered the concerns many young men in the United States do, like getting a job and saving up for a car.

In July 2009, one of Sami’s older brothers had returned to Kosovo to get married, and just before Sami was to fly to the Balkans with his brother Avni for the wedding, he had a terrible dream. “An angel grabbed me by the face and pushed me into the hellfire,” he would later tell a psychologist. At the wedding, Avni took a photograph of Sami; he’s clean-shaven and wearing a pressed white suit. He looks happy. On the flight back from the wedding, during the final leg of the journey to Tampa, the plane Sami and his brother were on hit turbulence, losing altitude quickly. “I thought we were going to crash,” Avni remembers. Sami looked horrified.

Sami-osmakac

Osmakac in 2009. (Photo courtesy of Osmakac family)

That’s when something changed in him, according to his family and mental health expertshired by both the government and the defense. Osmakac began to isolate himself from his siblings and attend the mosque frequently. He spoke of dreams about killing himself, and chastised family members for being more concerned about this life than what comes after.

In December 2009, Osmakac met a red-bearded Muslim named Russell Dennison at a local mosque. Dennison, who was American-born, was described by Osmakac as a “revert.” Muslims believe that all people are born with an understanding of the unity of Allah, so when a non-Muslim embraces Islam, some Muslims refer to this as reversion rather than conversion. Dennison went by the chosen name Abdullah; he says in a YouTube video that after being introduced to Islam, his faith grew stronger during a prison term in Pennsylvania. Osmakac’s dress changed after he met Dennison. Whereas he had once saved his money to buy nice shoes and Starter caps, he suddenly began to dress like Dennison, according to family members — cutting his pants high at the ankle, buying cheap plastic sandals and sometimes wearing a keffiyeh on his head. He refused to cut his beard, which he struggled to grow with any thickness, and he wouldn’t wear deodorant that contained alcohol.

It wasn’t just his physical appearance that was changing; by the beginning of 2010, his family also believed he was deteriorating mentally. He’d become paranoid and delusional. His skin was pale. He was sleeping on the floor of his bedroom and complained about nightmares in which he burned in hell. He stopped working at the family bakery because they served pork products. Near the end of the year, his family repeatedly asked him to see a doctor. He rebuffed them, saying that the doctors would want to kill him. (Osmakac later told a psychiatrist he in fact “was scared to go to a mental home.”

dennison

Russell Dennison (YouTube)

Meanwhile, Osmakac’s friendship intensified with the red-bearded revert. Dennison, whose videos on YouTube are posted under the username “Chekdamize7,” frequently preached about Islam and ranted about the corruption of nonbelievers. Osmakac’s family believed that Dennison encouraged his extreme views, often recruiting him to make videos. Among their efforts was a two-part series in which they argued combatively about religion with Christians they confronted on the sidewalk.

Over the next year, Osmakac, who was without steady employment, established a reputation as a firebrand in the local Muslim community. He was kicked out of two mosques, and lashed out at local Muslim leaders in a YouTube video, calling them kuffar and infidels. In March 2011, Osmakac made his way to Turkey, in the hopes of traveling by land to Saudi Arabia, according to his brother. He’d been told that holy water from Mecca was a cure-all, Avni says — that if he drank it, the nightmares would cease. But Osmakac never got much farther than Istanbul, after encountering multiple transportation mishaps, and getting turned away at the Syrian border by officials who refused to let him cross without a visa. He quickly ran out of money, lost his will and called home for help. His family in Tampa helped purchase a plane ticket for him to return to Florida.

Osmakac would later tell several mental health professionals that he was in fact more interested in traveling to Afghanistan or Iraq to fight American troops, and perhaps even find a bride there. “If I got to Afghanistan or Iraq, someone would marry me to their daughter,” he mentioned to one psychologist. Osmakac got back in touch with Dennison in Florida, and would talk often of returning to a Muslim land so he could marry.

Osmakac’s altercation with Keffer, April 16, 2011. (YouTube)

ON APRIL 16, 2011, Osmakac was outside of a Lady Gaga concert in Tampa. Larry Keffer, a Christian street preacher with short-cropped brown hair and a thick, white beard, was outside the concert as well. Keffer was wearing a fishing hat, a green camouflage shirt and blue pants.

“Sin is a slippery slope,” Keffer yelled through a megaphone to the Lady Gaga fans as someone else recorded the demonstration.

Most of the crowd ignored Keffer. A few concertgoers taunted him. He taunted them back. A police officer directing traffic refused to acknowledge the demonstration, while Keffer ranted about Lady Gaga and the devil. Osmakac finally confronted Keffer, pointing his finger in the preacher’s face.

“You infidel, I know the Bible better than you,” Osmakac told the preacher.

“What’s your message?” Keffer replied, talking into the megaphone.

“My message is, if y’all don’t accept Islam, y’all going to hell,” Osmakac said.

The men continued to provoke each other as people milled into the concert venue.

“Go have yourself a bacon sandwich,” Keffer told Osmakac.

“You infidel,” Osmakac said. “You infidel.”

As the argument escalated, Osmakac charged one of Keffer’s fellow demonstrators and head-butted him, bloodying the man’s mouth and breaking a dental cap. He then charged Keffer. Each wrapped his arms around the other, turning and twisting, until they broke free. The police officer managing traffic charged Osmakac with battery, giving him notice to appear in court. Osmakac was later arrested after failing to show up, Avni says, and his family had to bail him out; in just a few months’ time, Osmakac’s red-bearded friend would lead him straight into an FBI trap.

Screen-Shot-2015-03-02-at-3.51.58-PM

SAMI OSMAKAC AND Russell Dennison lived in Pinellas County, across the bay from Tampa. In September 2011, Dennison told Osmakac he knew a guy who ran a Middle Eastern market in Tampa. They should go see him, Dennison suggested. To this day, Osmakac doesn’t know why Dennison suggested this, or why he agreed to accompany him on the 45-minute drive to the store, called Java Village, near the Busch Gardens theme park.

When they arrived, Dennison introduced Osmakac to the owner, Abdul Raouf Dabus, a Palestinian. Dabus had flyers in his store promoting democracy, and he and Osmakac argued about the subject, with Osmakac contending that democracy and Islam were incompatible.

“Democracy makes the forbidden legal and the legal forbidden, and that’s greater infidelity,” Osmakac would tell Dabus. “Whoever enforces it is an infidel, is a Satan. Hamas is Satan. Muslim Brotherhood is Satan … If you don’t accept that God is the only legislator, then you become a polytheist, and that’s why I’m telling you.”

Osmakac didn’t know that Dabus would become an FBI informant. His work for the government has until now been secret.

According to the government’s version of events, Osmakac asked Dabus if he had Al Qaeda flags, or black banners. Osmakac disputes this, saying he never asked anyone for Al Qaeda flags.

Whatever the truth, the sting had just begun.

A psychologist appointed by the court later diagnosed Osmakac with schizoaffective disorder.

“He asked me if he can work a couple of hours, working and other stuff,” Dabus said in a phone interview from Gaza, where he now lives. “But it wasn’t really like a job. So basically, he was helping whenever he comes. And he got paid.” Dabus acknowledged he was paying Osmakac as the FBI was paying him.

In Tampa’s Muslim community, Dabus is well known. A former University of Mississippi math professor, Dabus was an associate of Sami Al-Arian, the University of South Florida professor who was indicted for allegedly providing material support to the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, in a case prosecutors argued proved successful intelligence-gathering under the Patriot Act. Dabus had worked at the Islamic Academy of Florida, an elementary and secondary private school for Muslims that Al-Arian had helped to found in Temple Terrace, a suburb of Tampa.

Dabus was among the witnesses in the Al-Arian trial, and his testimony was damaging to the government’s case. He testified that he had known Al-Arian only to raise money for charitable purposes, not for violence. During cross-examination, Dabus told the defense that he feared that Al-Arian’s trial meant Palestinians in the United States could no longer speak openly about the occupied territories. “There is no longer any security for the dog that barks in this country,” Dabus said.

He also questioned whether Al-Arian’s indictment suggested Muslims had become a new target for the U.S. government. “Our kids, will they have a future here?” he asked. “I don’t know.”

While Al-Arian would continue to battle federal prosecutors, living under house arrest in Virginia until finally agreeing to deportation to Turkey this year, Dabus remained in Tampa, active in the local religious and business community. But he acquired a reputation during this time for running up debts. From 2005 to 2012, he faced foreclosure actions on his home and businesses, as well as breach-of-contract and small-claims cases. In fact, when Dabus met Osmakac, he was in rough financial straits, records show. In July 2011, the bank holding the mortgage on his business’s building was granted approval to sell the property through foreclosure; Dabus owed $779,447.

It’s unclear why Dabus became an FBI informant, or for how long he worked with the government. He says he was doing his civic duty in reporting Osmakac and the young man’s interest in acquiring weapons, and had not previously worked with the FBI, though an FBI affidavit in the Osmakac case described Dabus as having “provided reliable information in the past.” Money is a common motivator for FBI counterterrorism informants, who can earn $100,000 or more on a single case. Dabus estimates the FBI paid him $20,000 for his role in the Osmakac sting, though insists money did not motivate him.

On November 30, 2011, after Osmakac had begun working for Dabus, the two drove around the Tampa area together as Dabus secretly recorded their conversation for the FBI. Osmakac asked if Dabus could help him obtain guns and an explosive belt. However, transcripts suggest he was also having trouble separating reality from fantasy. “In the dream, I was shown that everywhere you go, everything you do, hush your mouth,” Osmakac says. “Don’t say nothing. So, yes, the dream is real. Allah showed me that dream for a reason. And he’s also protected me for a reason.”

A psychologist appointed by the court later diagnosed Osmakac with schizoaffective disorder.

Osmakac and undercover FBI agent “Amir Jones.” (YouTube)

ABOUT THREE WEEKS after this conversation, on instructions from the FBI, Dabus introduced Osmakac to “Amir Jones,” an undercover agent. He might be able to help Osmakac obtain weapons, Dabus told him.

“What are you looking for, so that I know if it’s something I can get you or not?” Amir asks Osmakac.

“I’m looking for, even if … one AK, at least,” Osmakac says.

“OK.”

“And maybe a couple of Uzi, ’cause they’re better to hide.”

“OK. OK.”

“If you can get the long extension like for the AK and the Uzi, the long magazines—”

“They’re called banana magazine,” Amir says. “OK.”

“And … couple of grenades, 10 grenades minimum, if you can,” Osmakac says.

“Now, and that’s it?” Amir asks.

“And a [explosive] belt.”

For all Osmakac’s talk, the FBI’s undercover videos suggest he was less a hardened terrorist and more a comic book villain. While driving around Tampa with Amir, a hidden FBI camera near the dashboard, Osmakac described a plot to bomb simultaneously the several large bridges that span Tampa Bay.

“That’s five bridges, man,” Osmakac says. “All you need is five more people …. This would crush everything, man. They would have no more food coming in. Nobody would have work. These people would commit suicide!”

Amir Jones, behind the wheel of the car, offered a hearty laugh.

BACK AMONG FEDERAL law enforcement agents, according to the secret transcripts of their private conversations, there were plenty of reasons to joke at Osmakac’s expense. FBI employees talked about how Osmakac didn’t have any money, how he thought the U.S. spy satellites were watching him, and how he had no concept of what weapons cost on the black market.

The source of their amusement was also their primary source of concern. Osmakac was, in the FBI’s own words, “a retarded fool” who didn’t have any capacity to plan and execute an attack on his own. That was a challenge for the FBI.

“Once [the source] gives it to him, it’s his money, whether we orchestrated it or not.”

– Special Agent Taylor Reed

“Part of the problem is they want to catch him in the act,” FBI Special Agent Steve Dixon says, referring to federal prosecutors. “The attorneys do and stuff, but the problem is you can’t show up at a nightclub with an AK-47, in the middle of a nightclub, and pretend to start shooting people, or I mean people —”

“Right,” another speaker interrupts.

“— would get killed, just a stampede, just to get away from him,” Dixon finishes.

In constructing the sting, FBI agents were in communication with prosecutors at the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Middle District of Florida, the transcripts show. The prosecutors needed the FBI to show Osmakac giving Amir Jones money for the weapons. Over several conversations, the FBI agents struggled to create a situation that would allow the penniless Osmakac to hand cash to the undercover agent.

“How do we come up with enough money for them to pay for everything?” asks FBI Special Agent Taylor Reed in one recording.

“Right now, we have money issues,” Amir admits in a separate conversation.

Their advantage was that Dabus, the informant, had given Osmakac a job. If they could get Dabus to pay Osmakac, and then make sure Osmakac used his paycheck to make a payment toward the weapons, the agents could satisfy the Justice Department. “Once he gives it to him, it’s his money, whether we orchestrated it or not,” Reed says.

In conversations about this plan, FBI agents refer to Dabus as the “source,” short for confidential human source. “Jake” is FBI Special Agent Jacob Collins, who transcripts indicate worked closely with Dabus.

“The source has to tell him, ‘Hey, listen! You are gonna have to give [Amir] the three hundred bucks,’” says Richard Worms, the squad supervisor. “And that’s something Jake has the source tell him. ‘And I’ll take care of the rest … and here’s three hundred of my money for you.’ Is that something you accept?”

“That’s a feasible scenario,” Amir Jones answers.

“That’s what you’re going to do,” Worms says. “That way, the source has to be coached what to do.”

In order to avoid being vulnerable to entrapment claims, the FBI agents didn’t want their money being used to purchase their weapons in the sting. So they laundered the money through Dabus. In an interview, Dabus implicitly confirmed that arrangement, describing the $20,000 he estimates he received from the FBI as a mix of expenses and compensation.

“It also shows good intent,” Worms says of giving Osmakac the money, according to the transcripts. “He was willing to cough up almost his entire paycheck to get this thing going.”

“That does look really good,” concurs FBI Special Agent Taylor Reed.

Osmakac and Amir at a Days Inn in Tampa on January 7, 2012. (YouTube)

AMIR AND OSMAKAC arranged to meet at a Days Inn in Tampa on January 7, 2012. The FBI had the room wired with two cameras, a color one facing the headboard and a black-and-white one looking over the bed and toward the closet door, in front of which Osmakac would film his martyrdom video. Just as the FBI had orchestrated, Osmakac provided the cash to Amir as a down payment on the weapons.

The hotel surveillance video starts at 8:38 p.m. Osmakac is kneeling down on the floor and praying. He then stands and greets Amir, who has laid out the weapons on the bed. There are six grenades, a fully automatic AK-47 with magazines, a handgun and an explosive belt. Outside, a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device is assembled in the bed of Amir’s truck. None of the guns or explosives was functional, but Osmakac didn’t know that.

“You know, they saying they like three trillion in debt, they like 200 trillion in debt,” Osmakac had said, describing their plot. “And after all this money they’re spending for Homeland Security and all this, this is gonna be crushing them.”

Amir shows Osmakac the weapons one by one. He demonstrates how to reload the guns, and how to arm and throw the grenades, as Osmakac had never received weapons training.

“This one’s fully automatic,” Amir says, as Osmakac holds the AK-47.

Osmakac then slips on the suicide vest, as Amir showed him, and sits down in front of the closet, where he’ll record his video. Amir is seated in a chair facing Osmakac, holding the digital camera out in front of him.

The FBI was making a movie — all the agents needed was, in their words, a “Hollywood ending.” Osmakac would give them that final scene.

Osmakac had settled on an Irish bar, MacDinton’s, as his target. The supposed plan, which Osmakac dreamed up with Amir, was for Osmakac to detonate the bomb outside the bar, and then unleash a second attack at the Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino in Tampa, before finally detonating his explosive vest once the cops surrounded him.

But that didn’t happen. Instead, FBI agents arrested him in the hotel parking lot. He was charged with attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction — a weapon the FBI had assembled just for him.

After the arrest, according to the sealed transcripts, the FBI agents intended to celebrate their efforts over beers.

“The case agent usually buys,” one of the FBI employees is recorded as saying. Another adds: “That’s true — the case agent usually pops for everybody.”

Osmakac loading the fake car bomb with Amir. (YouTube)

HOW OSMAKAC CAME to the attention of law enforcement in the first place is still unclear. In a December 2012 Senate floor speech, Dianne Feinstein, chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, cited Osmakac’s case as one of nine that demonstrated the effectiveness of surveillance under the FISA Amendments Act. Senate legal counsel later walked back those comments, saying they were misconstrued. Osmakac is among terrorism defendants who were subjected to some sort of FISA surveillance, according to court records, but whether he was under individual surveillance or identified through bulk collection is unknown. Discovery material referenced in a defense motion included a surveillance log coversheet with the description, “CT-GLOBAL EXTREMIST INSPIRED.”

If he first came onto the FBI’s radar as a result of eavesdropping, then it’s plausible that as part of the sting, the FBI manufactured another explanation for his targeting. This is a long-running, if controversial process known as “parallel construction,” which has also been used by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration when drug offenders are identified through bulk collection and then prosecuted for drug crimes.

In court records, the FBI maintained that Osmakac came to agents’ attention through Dabus. The informant reached out to the FBI after meeting Osmakac, and soon offered him a job at Java Village.

At trial starting in May 2014, Osmakac’s lawyer, George Tragos, argued that the Kosovar-American was a young man suffering from mental illness, who had been entrapped by government agents.

A difficult defense to raise, entrapment requires not only that the government create the circumstances under which a crime may be committed, but also that the defendant not be “predisposed” toward the crime’s execution. “This entire case is like a Hollywood script,” Tragos told the jury, pointing out that the central piece of evidence was that Osmakac used government money to buy government weapons.

A psychologist retained by the defense, Valerie McClain, testified that Osmakac’s psychotic episodes, along with other mental health issues, made him especially easy for the government to manipulate. “When I talked to him most recently, he was still delusional,” McClain testified. “He still believed he could become a martyr.” Six mental health professionals examined Osmakac before his trial. Two hired by the defense and two appointed by the court diagnosed Osmakac with psychotic disorder or schizoaffective disorder. The pair hired by the prosecution said Osmakac suffered from milder mental problems, including depression and difficulty adapting to U.S. culture.

Tragos wasn’t able to tell the jury that FBI agents might have agreed with McClain’s assessment of Osmakac. The transcripts of the accidentally recorded conversations among FBI agents weren’t allowed into evidence, but after the trial, District Judge Mary S. Scriven did agree to unseal a number of them, which were heavily redacted by the government before being entered into the court file.

Prosecutors relied on the undercover FBI recordings and Osmakac’s own words to convict him. They played for the jury Osmakac’s so-called martyrdom video. They showed footage of Amir slipping over Osmakac’s shoulder the strap for the AK-47. They filled the courtroom with exchange after exchange of Osmakac’s hateful and violent rhetoric. Prosecutors played up Osmakac’s most ridiculous remarks, including his desire to bomb simultaneously the bridges that cross Tampa Bay. “The most powerful thing you can see are the defendant’s own words. His intent was to commit a violent act in America,” prosecutor Sara Sweeney told the jury.

Following a six-hour deliberation, jurors convicted Osmakac of possessing an unregistered AK-47 and attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction. In November 2014, he was sentenced to 40 years in federal prison.

“I wanted to go and study the religion … hoping that Allah is gonna cure me one day from the evil inside that I used to believe. But the doctors are saying it’s not evil — it’s mental illness.”

– Sami Osmakac

Entrapment has been argued in at least 12 trials following counterterrorism stings, and the defense has never been successful. Neither Abdul Raouf Dabus nor Russell Dennison testified in or provided depositions for Osmakac’s trial.

The government couldn’t produce Dabus, the FBI’s informant, because he had traveled to Gaza and Tel Aviv, where he says he was receiving treatment for cancer. He says his involvement with the FBI was limited to the Osmakac case — to reporting a suspicious man who was asking about Al Qaeda flags. Dabus disputes the FBI’s claim in court records that he was known to provide reliable information in the past.

“I did my job with them. I went away, and it is over,” Dabus says. “But I do not regret, and I would never regret to call again.”

Before Dabus left the country, the bank was granted approval to sell his Tampa home through foreclosure. His family owed $302,669, or about $50,000 more than the house was worth. Java Village is now shuttered. The signs are still on the outside of the building. Inside, the shelves are knocked over. Canned and dry goods litter the floor. Two dogs now guard the property.

Dennison, the red-bearded man who introduced Osmakac to Dabus, remains a mystery. He left the area shortly after Osmakac’s arrest, and emails he sent in late 2012 to a mutual friend he shared with Osmakac suggest he was fighting in Syria.

Osmakac’s family suspects much of Dennison’s story is a lie, and that he was, and likely still is, working with government agents. How else could Dennison have so conveniently delivered Osmakac to Dabus?

Confidential FBI reports on Dennison, copies of which were provided to The Intercept, do not address whether he’s been linked to a government agency. But the reports suggest the red-bearded man had a peculiar knack for becoming friendly with targets of FBI stings. After Osmakac’s arrest, FBI Special Agents Jacob Collins and Steve Dixon interviewed Dennison at Tampa International Airport, according to one report. Dennison was headed to Detroit, and from there, he said he hoped to go to Jordan to teach English. Dennison described how he was in contact with Abu Khalid Abdul-Latif, whose real name is Joseph Anthony Davis, a 36-year-old Seattle man who, like Osmakac, was troubled and financially struggling, lured by a paid informant into an FBI counterterrorism sting in June 2011. Abdul-Latif is serving 18 years for his crime.

Osmakac is now in USP Allenwood, a high-security prison north of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

“I was manipulated by [the FBI],” Osmakac says in a phone call from prison. He says he only wanted to move to a Muslim country, where he hoped to find a wife. Instead, he says, Dabus and the FBI exploited his mental problems and pushed him in different direction.

“I wanted to go and study the religion and get married, have children, just have nothing to do with this Western world,” Osmakac says. “I wanted to study Arabic and the religion in depth, hoping that Allah is gonna cure me one day from the evil inside that I used to believe. But the doctors are saying it’s not evil — it’s mental illness.”

Osmakac’s family is trying to raise money for an appeal.

“If my brother was truly part of a plot to kill people, I’d be the first one in line to condemn him,” Osmakac’s brother Avni says. “But my brother was mentally ill. We were trying to get him help. The FBI got to him first.”

This story was reported in partnership with the Investigative Fund at The Nation Institute.

Illustration by Jon Proctor for The Intercept

《纽约时报》

Boston Muslims Struggle to Wrest Image of Islam From Terrorists