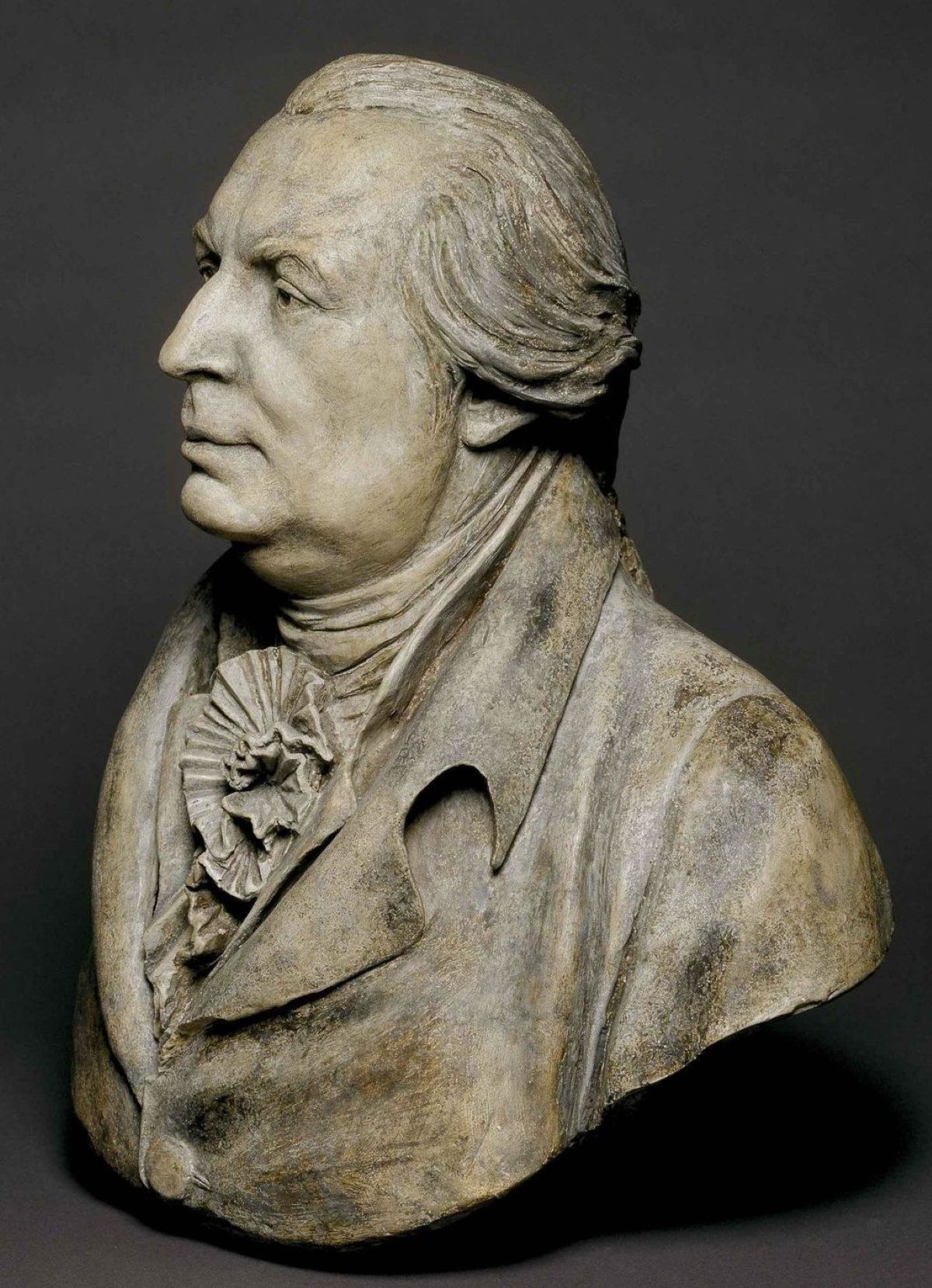

Gouverneur Morris on the Word "Liberty": An Empty Sound?

https://oll.libertyfund.org/reading_room/2022-07-14-Miller-Morris-Liberty

Is it enough for a nation to have a constitution purporting to guarantee liberty and justice? Gouverneur Morris would say emphatically no: a consistent theme in his writings is that a constitution must be suited to the people it governs. As noted in the last post, he understood human nature, and the conflicting interests that agitate society.

Related links:

What would Morris say about Americans of today? Would he believe we are suited to the constitution we have? In considering this question, it is worth looking at his thoughts about why the French of the late 18th century were not suited to American-style democracy. Morris arrived in Paris in early 1789, just as the first stirrings of the French Revolution, inspired by events in America, were underway. Morris soon concluded, however, that an American-type constitution would not work in France. The French, Morris said, “want an American Constitution with the Exception of a King instead of a President, without reflecting that they have not American Citizens to support that Constitution," and he accurately predicted the turmoil and chaos -- and in the end, the despotism -- that would result. The claim by the first and all succeeding revolutionary regimes of being "patriotes" (all opponents were branded "aristocrats") and, later, the omnipresent catch phrase "Liberté, Equalité, Fraternité." did not impress Morris. "I have liv’d too long to regard men’s expressions," he wrote to Madame de Lafayette,

so that all sentences rounded off by fair or foul words, such as liberty, patriotism, virtue, treason, aristocracy, crime, are to me the equivalent of blank paper.

Some months after his arrival, he was waiting for his carriage to pick him up at the Palais Royale when

the Head and Body of Mr. de Foulon are introduced in Triumph. The Head on a Pike, the Body dragged naked on the Earth...This mutilated Form of an old Man of seventy five is shewn to Bertier, his Son in Law, the Intend[ant] [royal administrative agent] of Paris, and afterwards he also is put to death and cut to Pieces, the Populace carrying about the mangled Fragments with a Savage Joy. Gracious God what a People!

The propensity to mob violence and its use as a political tool by the revolutionary leaders was one reason he considered the people unready for democratic government: the butchering of the old man was one of many horrific scenes that would take place in France before and during the Terror. Morris did not believe his fellow citizens would do such a thing; that July night, in a letter to a friend, he reflected:

I was never till now fully apprized of the mildness of American character. I have seen my countrymen enraged and threatening. It has even happened that in an affray some Lives were lost. But we know not what it is to slay the defenseless Victim who is in our Power.

Corruption was another obstacle identified by Morris. It had been at the core of the previous royal regimes, with offices and contracts bought and awarded without regard to qualifications. The new National Assembly was also politically corrupt, dominated by members seeking to profit from the new government and at the same time subject to the rhetoric of demagogues capitalizing on popular discontent. Morris wrote to Jefferson about it:

Virtue once gone Freedom is but a Name for I do not believe it to be among possible Contingencies that a corrupted People should be for one Moment free.

Mutual trust was also required for a successful government. In France, he told Jefferson, rampant

Suspicion, that constant Companion of Vice and Weakness, has loosened every Band of social Union and blasts every honest Hope in the Moment of its budding.

Unwillingness to govern with moderation and disinterest in compromise also doomed the French Revolution. Morris observed with dismay "the Violence and Excess of those Persons who, either inspired by an enthusiastic Love of Freedom or prompted by sinister Designs, are disposed to drive every Thing to Extremity" and to disaster. And so it proved: in the two and a half years from the time news of Morris’s nomination as minister to France arrived in early 1792 until he was relieved of the post in August 1794, the French government had changes of power entailing seven different heads of foreign affairs. Four of them were condemned as traitors and three of them died on the guillotine while one defected to the Austrians. Each successive administration was the mortal enemy of its predecessors; the "Constitution of 1791" had soon proved unworkable and was denounced by all who had previously championed it.

It is important to know that Morris genuinely loved France. He wished for the happiness of its people; but, he told a fellow diplomat a month before the King was executed, he did not indulge in the "Illusions of Hope" for establishment of a good constitution and government because he did not yet perceive

that Reformation of Morals without which Liberty is but an empty Sound.

Morris gives us much to think about in our current times.